“We are not so very different, you and I.” — George Smiley

Tomas Alfredson’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011) is a cold, coiled, and relentless march into the gray, rain-lashed corridors of British espionage—a film that exchanges Bond’s swagger for bureaucratic unease, where information is traded like poison and every conversation feels weaponized. The film is sheer confidence: so sure of itself, it expects you to keep up, get lost, and piece the puzzle together from the hushed fragments left in close-up reactions and glances across smoke-filled rooms. This is spy cinema not as spectacle, but as slow-burning existential puzzle.

A key element of the film’s mood is its distinctive brutalist aesthetic, which powerfully evokes the Cold War mentality not only behind the Iron Curtain but also in the West. Alfredson and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema immerse viewers in a London setting defined by greying, tired walls, bleak drizzle, and decaying interiors that feel as cold and institutional as the very espionage world they depict. This use of brutalism—with its bare concrete textures, utilitarian spaces, and sense of institutional decay—does more than create atmosphere; it visually projects the emotional and material exhaustion of a Britain entrenched in paranoia and internal rot. The characters seem physically and emotionally hemmed in by these spaces, reinforcing the film’s themes of secrecy, alienation, and moral corrosion.

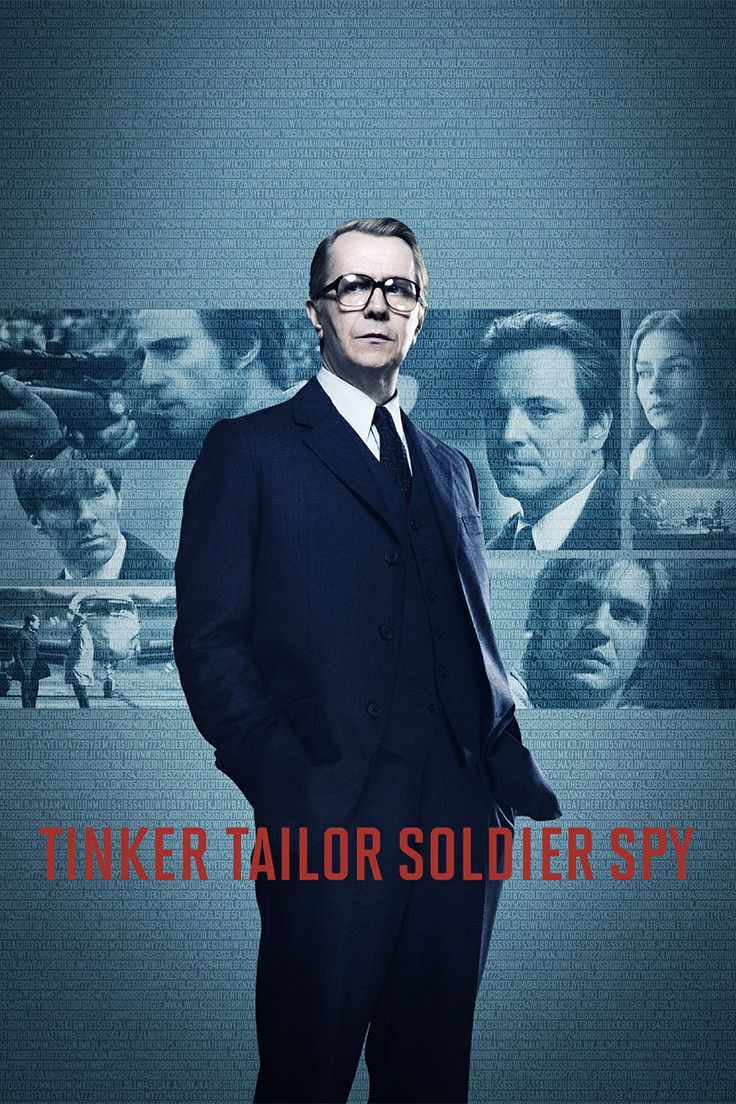

There are no car chases or shootouts to speak of—just a masterclass in stillness where tension arises from precisely what remains unspoken. The film is closer to an autopsy than a thriller, dissecting the social and emotional costs of lives devoted to deception. It begins with a botched operation in Budapest—Jim Prideaux (Mark Strong), one of “the Circus’s” best agents, is captured in a tense, almost wordless scene that sets a tone of brooding unease. The fallout leads to a purge of the leadership, with Control (John Hurt) forced out and George Smiley (Gary Oldman), his quietly watchful confidant, retired—though soon to return for an unofficial mole hunt.

From there, the narrative unfolds elliptically, like a mosaic of recollections and betrayals, requiring viewers to assemble the truth from fractured glimpses. Gary Oldman’s Smiley is the film’s anchor—his performance a masterclass in minimalism and subtext. He’s the ultimate observer, haunted by decades of institutional compromises and personal betrayals.

The supporting cast is nothing short of exceptional, elevating the film through richly textured performances that bring vibrant life to an otherwise reserved script. Colin Firth as Bill Haydon delivers a quietly magnetic portrayal, his charm barely concealing the complexity beneath. Tom Hardy’s Ricki Tarr injects raw energy and restlessness, perfectly contrasting the film’s restrained atmosphere. Benedict Cumberbatch’s Peter Guillam is adept at conveying subtle shifts in allegiance and tension, his nuanced portrayal deepening the intrigue. John Hurt’s brief but potent presence as Control exudes weary gravitas, setting the tone for the murky world of espionage. Mark Strong as Jim Prideaux balances stoicism with vulnerable humanity, particularly in moments laden with pain and regret. Other supporting actors such as Ciarán Hinds, Toby Jones, and Kathy Burke contribute layered, compelling portrayals of individuals trapped within the machinery of the Circus. What binds these performances is a reliance on subtlety—expressing volumes through nuanced gestures and lingering silences, the cast anchors the complex narrative in a palpable human reality.

At its core, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is less a whodunnit than an exploration of institutional decay and emotional repression. The brutalist aesthetic mirrors this decline: just as the concrete and ochre walls close in on the agents, so too does the film reveal a Britain worn down by secrets and internal contradiction. Love and loyalty are liabilities in this world where everyone is alienated. The story’s emotional heart revolves around the search for a deeply embedded mole within the Circus—an elusive betrayal that shakes the organization to its core. The film carefully avoids easy reveals, maintaining a deliberate tension and exemplifying the emotional cost that the espionage game of the era had on everyone involved.

The film also explores themes of repressed queerness, class stratification, and misogyny, linking these to the numbing demands of espionage. The gloomy visuals and tightly controlled dialogue echo the emotional constraints on these men, underscoring that beneath the seemingly impenetrable exterior lies a fragile, fragile human cost.

This film is not an easy watch. Its elliptical storytelling, coded conversations, and subtle body language demand patience and multiple viewings. Yet that opacity is part of its power—uncertainty and not-knowing become central to the experience, enhanced by Alberto Iglesias’s restrained score and the claustrophobic mise-en-scène. Unlike many spy films, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is about process and detection, not action or glamour. Its cold, meticulous pacing trades on the cerebral seduction of uncovering hidden truths rather than adrenaline-fueled confrontations.

Ultimately, the film refuses easy resolutions. Though Smiley uncovers the mole and the Circus is superficially restored, there’s no real victory—only the acknowledgment of profound damage, both personal and institutional. The brutalist setting, with its unyielding, somber lines, stands as a perfect metaphor for this unresolved tension. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is a masterclass in unease and ambiguity, a film that stays with you because it reveals what you’ll never fully know about loyalty, betrayal, and the cost of secrets in a world where the line between friend and enemy is always blurred.