“What has happened to the world? You have every convenience and comfort, yet no time for integrity.” — Leopold

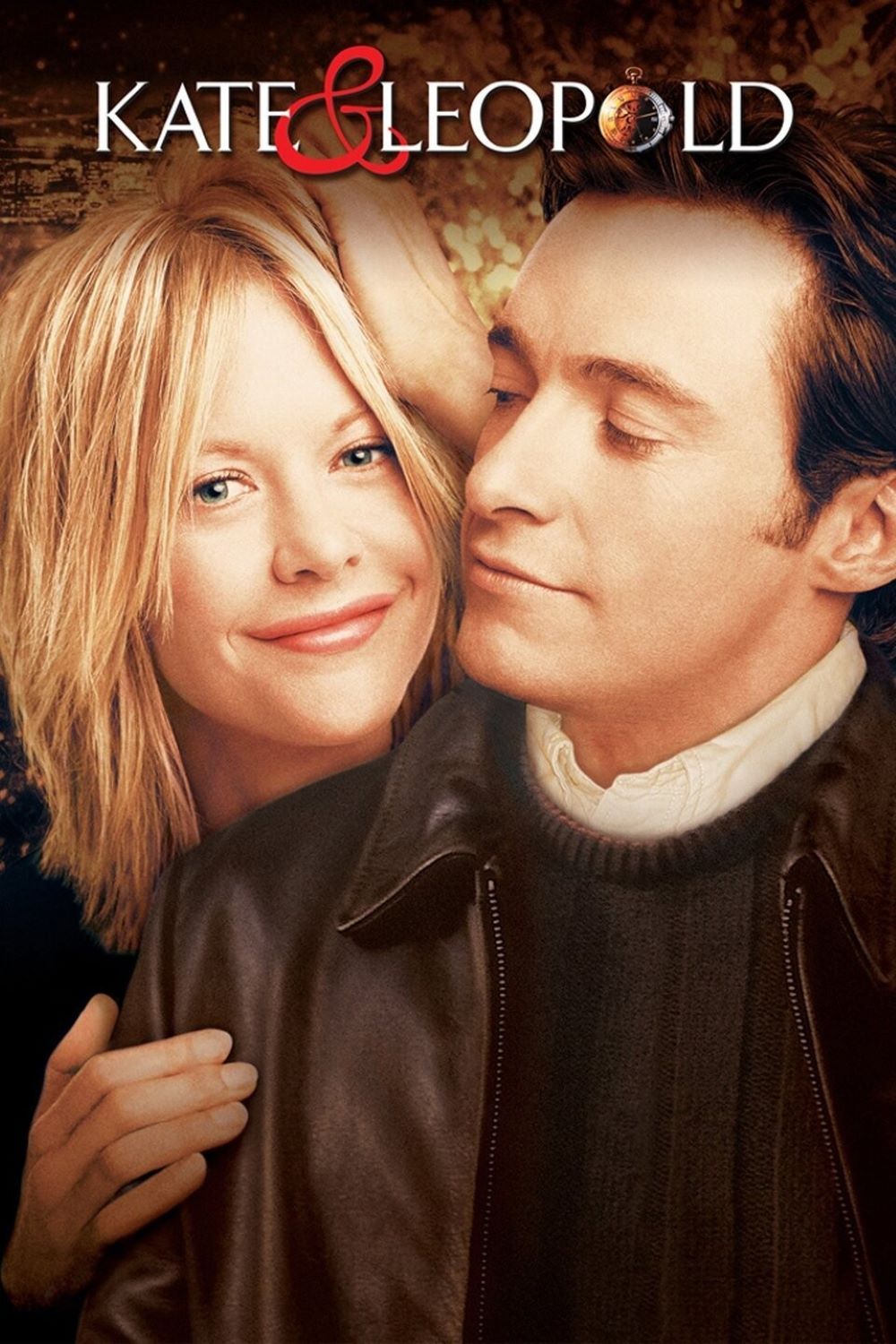

Kate & Leopold is one of those romantic comedies that sneaks up on you with its old-school charm, even if it doesn’t always stick the landing. Released in 2001, it catches Hugh Jackman right after his breakout as Wolverine in the first X-Men film, during that early stretch of hits leading toward epics like The Fountain, giving him a chance to shine in pure rom-com mode before the superhero world fully claimed him. It’s a time-travel tale starring Jackman as a 19th-century duke and Meg Ryan as a modern-day exec, and while it’s predictable in spots, it delivers some genuinely sweet moments amid the silliness, boosted by his fresh, pre-typecast appeal.

The setup is pure fantasy fodder. Leopold, the third Duke of Albany, lives in 1876 New York, tinkering with an elevator prototype that accidentally rips a hole in time. His descendant Stuart, a bumbling scientist played by Liev Schreiber, drags him to the present day. Leopold lands in modern Manhattan, bewildered by cars, skyscrapers, and people who don’t stand when a lady enters the room. Enter Kate McKay, Meg Ryan in full quirky career-woman mode, who’s too busy chasing a promotion to notice the fish-out-of-water nobleman crashing at her place. Her roommate Charlie, a slacker pianist, thinks Leopold’s a method actor at first, leading to some fun roommate hijinks.

What works best is Hugh Jackman’s effortless charisma as Leopold. He nails the role with wide-eyed wonder and impeccable manners, riding a horse through Central Park to chase a mugger, whipping up gourmet meals from sparse ingredients, and delivering lines about life’s simple pleasures—like how food must taste good to nourish the soul—with total sincerity. It’s disarming. Leopold isn’t just a pretty face; he’s a walking critique of 21st-century rudeness. When he calls out advertisers for peddling tasteless margarine or marvels at how folks wolf down burgers without savoring them, you can’t help but chuckle. His old-world chivalry clashes hilariously with New York’s hustle, like when he stands every time Kate leaves the table, leaving her exasperated but secretly charmed.

Meg Ryan holds up her end too, bringing that familiar rom-com energy she perfected in the ’90s. Kate’s a high-powered market researcher obsessed with a big pitch for some farmer’s butter spread—ironic, given Leopold’s later meltdown on set. She’s jaded from a recent breakup with Stuart, prioritizing work over everything, but Leopold slowly cracks her shell. Their first real connection comes over a picnic where he waltzes her around a rooftop to a hired violinist, and yeah, it’s corny, but Jackman sells it. Ryan’s got great chemistry with him; you buy their spark even when the script strains. Liev Schreiber steals scenes as Stuart, evolving from jealous ex to unlikely matchmaker, while Breckin Meyer adds comic relief as Charlie, who learns to woo his crush by channeling Leopold’s authenticity.

The fish-out-of-water gags land most of the laughs. Leopold navigating subways, elevators (his invention, after all), and TV commercials feels fresh enough, especially since the movie leans into his culture shock without overdoing slapstick. There’s a memorable bit where he tours modern New York, gaping at the Brooklyn Bridge and declaring it a marvel, only to learn it’s named after his investment. Director James Mangold keeps things light, blending screwball elements with a touch of Somewhere in Time nostalgia. The score swells romantically, and the production design pops—Leopold’s Victorian tux against neon signs is a nice visual contrast. Early 2000s rom-coms loved these fish-out-of-water tales—like The Holiday or Two Weeks Notice—but this one stands out for its sincere take on manners as a cure for modern cynicism.

But let’s be honest: Kate & Leopold has flaws that keep it from greatness. The time-travel rules are fuzzy at best. Leopold has to return to 1876 or the timeline implodes—elevators stop working, chaos ensues—but it’s hand-waved with vague portal talk. Stuart’s asylum stint feels mean-spirited, and the third act rushes into melodrama. Some supporting bits drag, like the endless ad pitch subplot, and the pacing dips mid-film when everyone’s just hanging out. The plot’s contrived overall, with that bridge-jump climax feeling abrupt, but the earnest vibe carries through.

Still, the romance earns its payoff. Kate and Leopold aren’t insta-lovers; they bicker over integrity versus ambition, with Leopold pushing her to taste life fully and Kate grounding his idealism. Their Central Park chase and final ball scene in 1876 deliver genuine swoon factor. It’s not subversive—Kate ditches her career for corsets, after all—but it celebrates courtesy and heart in a cynical world. Compared to edgier rom-coms like When Harry Met Sally, this one’s softer, more fairy tale than reality check. Ryan’s quirky energy bounces off Jackman’s poise, creating sparks that feel earned, even if the career sacrifice lands a bit dated now.

For a 2001 release, it holds up surprisingly well. No cell phones dominate every scene, letting face-to-face charm shine. Jackman’s glow makes Leopold believable as a duke who’d invent the elevator, and Ryan reminds us why she was America’s sweetheart. It’s PG-13 for mild language and innuendo—nothing racy, safe for date night or family viewing. Critics were mixed; some praised the manners humor but called the plot preposterous, which nails it. Watch it today, and it’s a charming time capsule, as out-of-step as Leopold in a subway.