In 1960s, Lester Bullard lives alone in the mountains of Tennessee. Abused as a child and scorned as an adult, Bullard is the type of person that most people try to ignore. He’s angry, bitter, and not all that knowledgeable about the world outside of his own fevered imagination. Having been evicted from his home, he moves into an abandoned shack where he spends his time voyeuristically watching the teenagers who sneak off to the isolated mountains so that they can fool around in their cars without being harassed by the grown-ups. When Bullard stumbles across two dead bodies in a car, it doesn’t so much send him on a downward spiral as much as it just accelerates the only fate that can be waiting for someone like Lester Bullard. Bullard does some truly disturbing things but, as the narrator reminds us, he’s “a child of God, much like yourself perhaps.”

(No, definitely not like me! Though I do get the narrator’s point.)

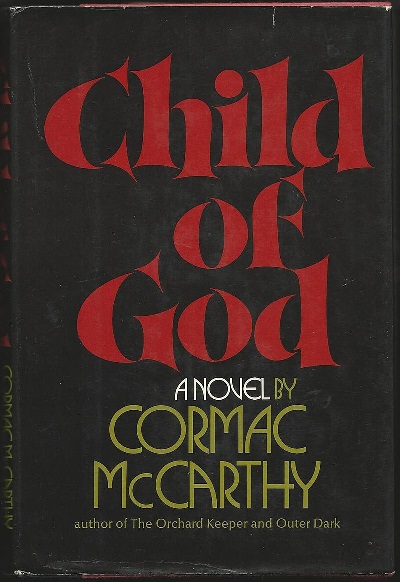

First published in 1973, Child of God was Cormac McCarthy’s third novel. It tells a disturbing story and one that will leave readers unsettled. Inspired by the type of macabre tales that used to be told around campfires, it’s a novel of cold, gothic horror. McCarthy’s prose creates such an atmosphere of darkness that it’s difficult to read the novel in one sitting. You almost have to put the book down so you can step outside and take a deep breath after some of the more grotesque moments. Child of God is also a character study of a man living on the fringes of what most people would already consider to be the fringe of society. Just as the people living on the East and West Coasts have rejected the citizens of Appalachia, Appalachia has rejected Luster Bullard. The book links Bullard to the violent history of Appalachia, with the Bullard family having been involved in many of the feuds that helped to define the region. McCarthy’s matter-of-fact prose serves to make Bullard’s crimes all the more disturbing, with McCarthy refusing to give the reader the easy out of a traditional, guns-blazing ending. Bullard’s ultimate fate feels almost as random as his crimes, challenging the idea of any sort of karmic justice. In the end, Bullard is destined to become another barely-remembered regional legend, like Ed Gein or the Bloody Benders. By telling his story without a hint of melodramatic excess, McCarthy leaves the reader with no choice but to consider that the world is full of real Lester Bullards.