Since it’s impossible for me to talk about anything without somehow relating it to a movie, I guess it makes sense that my reaction to San Francisco winning the World Series was to write a review of the award-winning, 1974 disaster film Earthquake. If the Rangers had won, I would have been obligated to write up a review of No Country For Old Men.

But anyway, Earthquake…

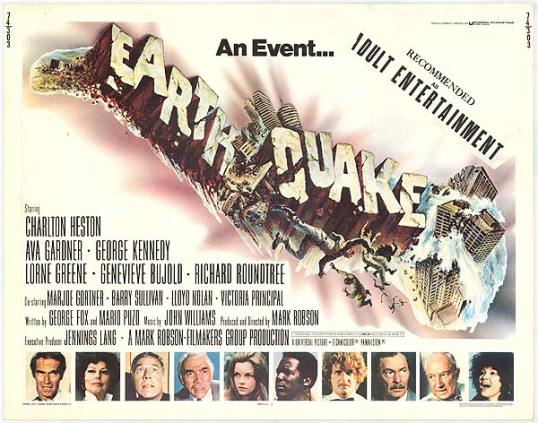

So, Earthquake is one of those movies from the 70s in which a large group of different characters had to deal with some sort of cataclysmic disaster that could, in theory, have happened in reality as well as up on the movie screen. There were apparently about 2,000,000 of these films made between 1970 and 1980 and they all had titles like Hurricane, Tornado, Big Fire, Asbestos, Flash Flood, Lava Flow, Khardashian, Avalanche, and, of course, Earthquake. These movies always featured an “all-star” cast of people that nobody had ever actually heard of and I guess part of the fun was trying to guess who would survive and who would die. Apparently, they were the 1970s version of Dancing With The Stars. Call it Dying With Celebrities.

Earthquake is one of best known of these films. Apparently, it made a lot of money in 1974 and it won Academy Awards for its earthquake effects. Bleh. Whatever. Have you ever really sat down and looked at a list of the movies that have won at least one Academy Award since they first started handing those things out? Earthquake is like a 6 hour movie and Los Angeles doesn’t start shaking until halfway through. The Earthquake itself only lasts for 15 minutes and it’s kind of impressive to watch but it’s 15 minutes out of 360.

Before the earthquake hits, we get to meet the usual cross-section of humanity. Charlton Heston is an architect who is married to Ava Gardner who is the daughter of Heston’s boss, who is played by an actor named Lorne Greene who appears to be younger than either Heston or Gardner. Heston has a mistress who is played by Genevieve Bujold who is really pretty, sweet, and boring. Gardner is none of these things but she is a foul-mouthed alcoholic who fakes suicide attempts so I was pretty much on her side as far as the whole love triangle is concerned. After the Earthquake, Heston and Greene and a bunch of accident-prone extras are stuck in the ruins of sky scraper. Heston grimaces a lot in this film but you know what? Say what you will about Charlton Heston’s politics or his clenched-teeth acting style, the man knew how to wear an ascot.

While Heston is torn between Gardner and Bujold (a plot development that reportedly inspired the famous Sartre play No Exit), Richard Roundtree just wants to jump over stuff on his motorcycle. That’s right — John Shaft is in this movie and we can dig it. He’s a professional daredevil. He’s also a surprisingly dull actor. Who would have guessed that, without a theme song playing, Shaft would turn out to be so boring? Still, there’s a really cool scene where Roundtree tries to ride his motorcycle through Los Angeles in the middle of the earthquake and the film is worth watching for his all-flare stunt daredevil costume if nothing else. Plus, Roundtree’s playing a character named Miles here and I like that name.

There’s another subplot. It involves George Kennedy as a blue-collar cop who does what he has to do to try to maintain the peace before and after the Earthquake. Bleh. I mean, Kennedy actually gives a pretty good performance and he’s probably the most likable character in the film but seriously — Bleh.

And finally, this collection of humanity is rounded out by an aspiring actress (played by actress Victoria Principal who, four years earlier, had made history by being the first woman to successfully seduce actor Anthony Perkins and no, I don’t want to go into how I know that) and the psychopathic grocery store manager who is obsessed with her. The grocery store manager is played by former child evangelist and 70s exploitation icon Marjoe Gortner. Much as in the later film Starcrash, Gortner projects a remarkably unlikable vibe that works well for his character. He also has a really bad perm and a mustache and his performance is so sublimely bad that it’s actually pretty good. As for Principal, her character here is apparently the owner of 1974’s most ginormous afro and, like most women in the 70s, really should have considered wearing a bra. It’s hard to really judge Principal’s performance because any time she’s on-screen, you just start thinking, “Oh my God, she had sex with Norman Bates but somehow, she thinks she’s too good for Marjoe Gortner?”

These are the characters that we follow as Los Angeles is destroyed on-screen. None of them are really much more than cardboard cut outs but there’s something oddly comforting about how shallow and predictable they all are. Add to that, most of them end up dead so if you do dislike them, you’ll find a lot to enjoy. You’ll especially enjoy the film’s final few moments unless, like me, you can’t swim and you’re terrified of drowning. If you’re like me, that scene might give you nightmares.

Flawed as it may be, I still have to recommend this movie as 1) a time capsule and 2) as a quintessential piece of American camp. Every line of dialogue, every performance, every image, and every scene in Earthquake simply screams 1974. I guess the best way to look at Earthquake is to think about it as if the movie’s a time machine. You might not like where the machine takes you but you’re still going to get into the damn thing and, once you find yourself stuck in Iowa in the year 1835, you’ll find someway to force yourself to be entertained because otherwise, you’re just hanging out in Iowa in 1835.