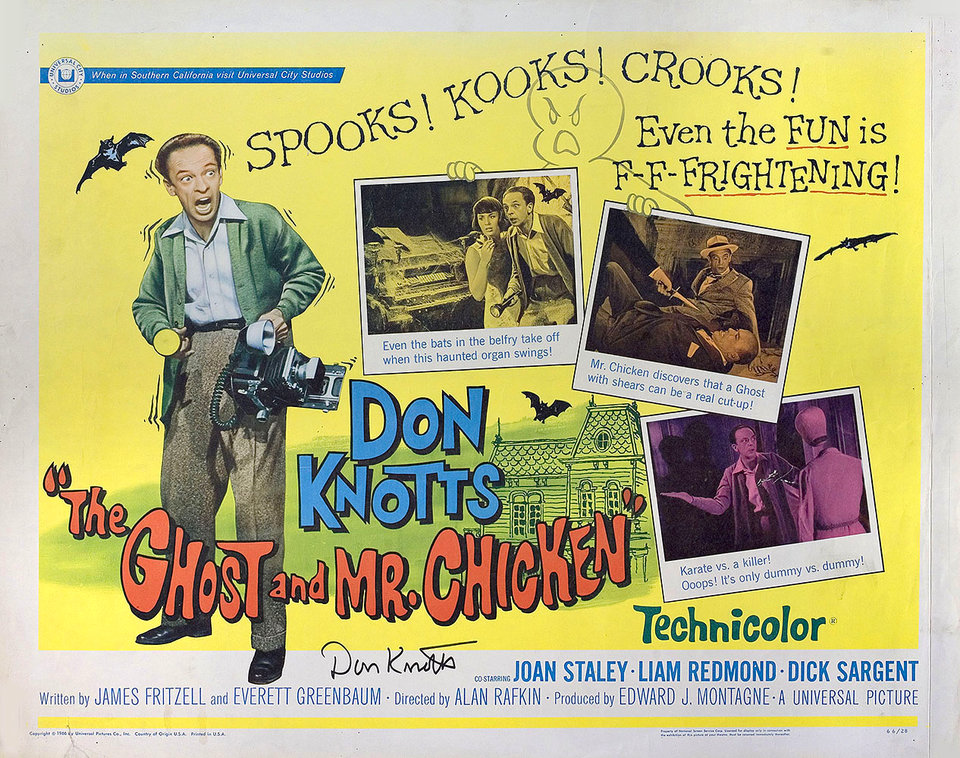

I love Don Knotts. I’m one of those people who have watched every episode of THE ANDY GRIFFITH SHOW (1960-1968) multiple times. And while it’s true that there are good episodes in the last three seasons, the series was at its best when Sheriff Andy Taylor and his sidekick Barney Fife were serving the townsfolk of Mayberry, North Carolina during the first five seasons. In Barney Fife, Don Knotts created one of the best characters in television history, earning five Emmy Awards in the process. When Don Knotts left the series at the height of its popularity, the first movie he made was THE GHOST AND MR. CHICKEN!

In THE GHOST AND MR. CHICKEN, Knotts plays Luther Heggs, a meek typesetter at a small-town newspaper in Rachel, Kansas, who dreams of being a serious reporter but is treated like a joke by nearly everyone around him. When the town prepares for the 20-year anniversary of an unsolved murder at the supposedly haunted Simmons Mansion, Luther unexpectedly gets a chance to prove himself. He volunteers to spend the night alone in the mansion to see if it really is haunted. As you might expect, Luther is scared out of his mind as he hears banging on the walls, discovers secret passageways, and observes blood-stained organs playing themselves. The night culminates with Luther seeing a portrait of poor Mrs. Simmons with gardening shears piercing her throat! By surviving the night, and then telling the truth about what he experienced, Luther just may uncover a real crime being committed behind all of this “supernatural” activity!

Since Don Knotts left THE ANDY GRIFFITH SHOW to pursue a movie career, I’m glad to report that his decision to star in THE GHOST AND MR. CHICKEN was a really good choice. His performance is a masterpiece of physical comedy. Sure, Knotts trembles, shakes and delivers his lines in his awkward, nervous way for a lot of laughs, but he also provides a vulnerability that really makes you root for him. Knotts knew how to play lovable losers in a way that shows a quiet decency. He may actually be scared, and he may seem like a real pushover, but he also finds the courage to do the right thing even when it’s not easy. This was true for Barney Fife, and it’s also true for Luther Heggs in THE GHOST AND MR. CHICKEN.

Aside from Don Knotts, THE GHOST AND MR. CHICKEN has a solid supporting cast! Joan Staley is very beautiful as Luther’s love interest, Alma. Staley was a Playboy Playmate in 1958, so I can definitely see why Luther is in love. I like the fact that her Alma is more than just a pretty face. Rather, she’s one of the few people who sees Luther as more than a joke, which makes her even more appealing. Meanwhile, Luther’s newsroom boss (Dick Sargent) and office rival (Skip Homeier) never miss an opportunity to be condescending. The director Alan Rafkin directed 27 episodes of THE ANDY GRIFFITH SHOW, so he definitely knows how to get the best comedy out of Knotts and the rest of his cast. He also keeps the tone light, with the haunted house set pieces playing out like gentle, kid-friendly chills rather than anything truly scary. The blood-stained organ / garden shears sequence in the mansion is especially effective, with Don Knotts perfectly walking the line between raging fear and slapstick comedy. Signaling that there was a big audience for Don Knotts in the movies, THE GHOST AND MR. CHICKEN proved to be a box office hit, taking the number one spot during its first week of release, and grossing about eight times its budget!

Ultimately, THE GHOST AND MR. CHICKEN endures because it understands the special qualities of its star. Don Knotts is funny, and he’s also human. He may be scared out of his mind, but he also has decency and an ability to find courage when he must. In that way, it’s a comfort movie, a should-be Halloween staple, and finally, a reminder that sometimes the bravest person in the room is the one who can’t quit shaking.