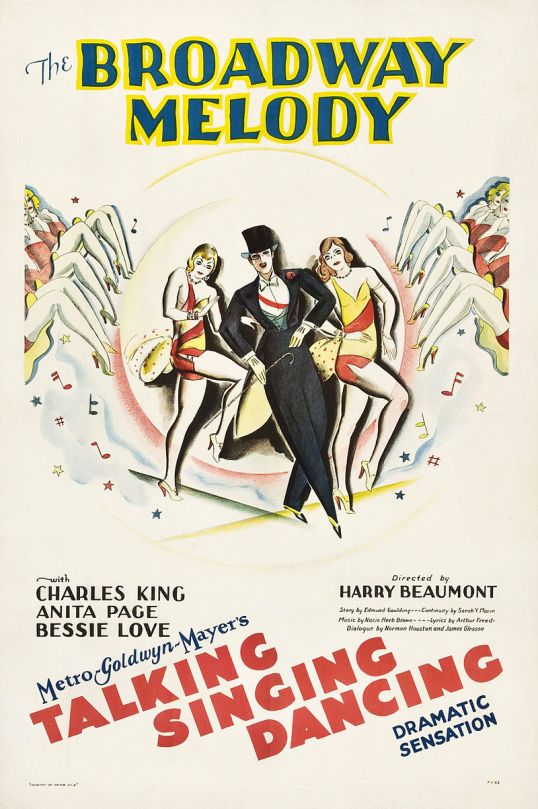

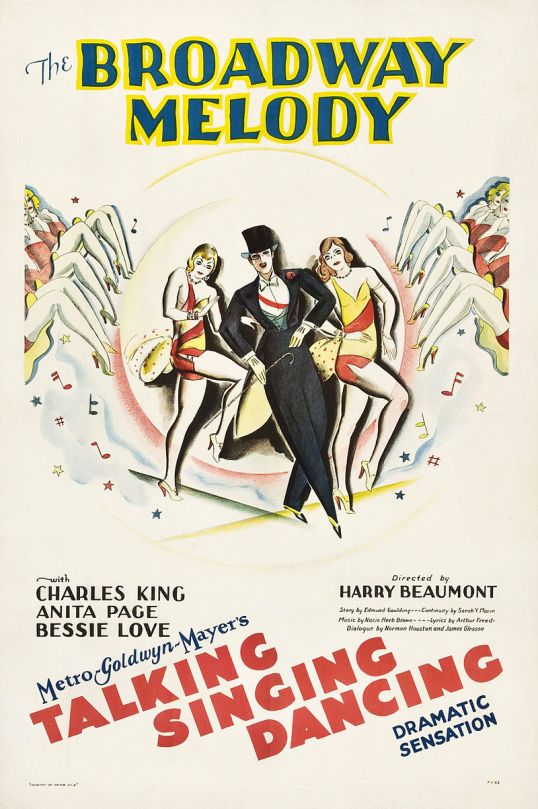

Oh, The Broadway Melody.

Where to begin?

First released way back in 1929, The Broadway Melody is a historically significant film. You really can’t talk about the development of film — especially sound film — without taking at least a few minutes to acknowledge The Broadway Melody. It was the 2nd film to ever win the Oscar for Best Picture (or Best Production, as it was called back then) and it was the first sound film to win the Oscar. (In fact, it would be 83 years before another silent film won Best Picture and it’s debatable whether or not The Artist can really be considered a silent film in the same way that Wings was silent film.) It was also the first musical to win best picture and some people consider it to be the first true musical to have ever been produced. It was such a huge box office success that it could be argued that The Broadway Melody is responsible for nearly every musical that followed it.

To say that The Broadway Melody tells a familiar story would be an understatement. I’ve read a few reviews that have suggested that the clichés in this film really weren’t clichés until after The Broadway Melody was released but I’ve seen enough silent films to know that this is not the case. It tells the story of two sisters who want to be stars. After spending years working in vaudeville, they’ve been invited to perform in a revue that’s being produced by Francis Zanfield (Eddie Kane).

(I assume that Zanfield was meant to be a stand-in for Florence Ziegfeld, himself the subject of a later Best Picture winner, The Great Ziegfeld.)

The sisters are Hank (Bessie Love) and Queenie (Anita Page). Hank is the driven one. Hank is the one with the raw talent and she’s also the one who best understands how the business of entertainment works. Her younger sister, Queenie (Anita Page), may not have Hank’s drive or quite the same level of talent but she does have beauty. Guess who finds the most success?

Songwriter Eddie Kearns (Charles King) is engaged to marry Hank but soon, both he and Queenie find themselves falling in love. Not wanting to hurt her sister, Queenie instead runs off with a notorious playboy named Jock Warner (Kenneth Thomson).

As I stated previously, The Broadway Melody has not aged well. The fact that it’s one of the first sound films just allows contemporary viewers to hear the creakiness of the plot. As impressive as sound film was to audiences in 1929, it’s obvious today that the cast and crew of The Broadway Melody were still struggling to figure out how to work with the new technology. As a result the performances are still a bit too broad, which only serves to make the film seem even more melodramatic than it actually is. As for the songs, they’re not particularly memorable. I always enjoy backstage musicals but Broadway Melody is no 42nd Street.

I did appreciate the relationship between Bessie Love and Anita Page. That was one of the few things about the film that felt real to me, perhaps because I have three older sisters. Interestingly enough, when Anita Page died in 2008, she was the last surviving attendee of the first Academy Awards ceremony.

The Broadway Melody was named the Best Picture of 1929. This was the year that the winners were selected by a committee and there were no official nominations. Though the notes from the meeting indicate that there was some consideration given to awarding the Best Actress Oscar to Bessie Love, Best Picture was the only Oscar that The Broadway Melody received.

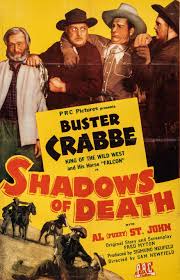

After a railroad agent is murdered and his map of the future locations of the railroad is stolen, Billy Carson (Buster Crabbe) rides into a frontier town and searches for the guilty party. Fortunately, for Billy, his best Fuzzy Q. Jones is the mayor, the sheriff, and the town barber! Unfortunately, local gunslinger Clay Kincaid (Eddie Hall) wants to make a name for himself by taking on the famous Billy Carson. Corrupt businessman Landreau (Charles King) encourages Clay by lying to him and telling him that Bully is planning on stealing Clay’s girl, Babs (Dona Dax).

After a railroad agent is murdered and his map of the future locations of the railroad is stolen, Billy Carson (Buster Crabbe) rides into a frontier town and searches for the guilty party. Fortunately, for Billy, his best Fuzzy Q. Jones is the mayor, the sheriff, and the town barber! Unfortunately, local gunslinger Clay Kincaid (Eddie Hall) wants to make a name for himself by taking on the famous Billy Carson. Corrupt businessman Landreau (Charles King) encourages Clay by lying to him and telling him that Bully is planning on stealing Clay’s girl, Babs (Dona Dax).