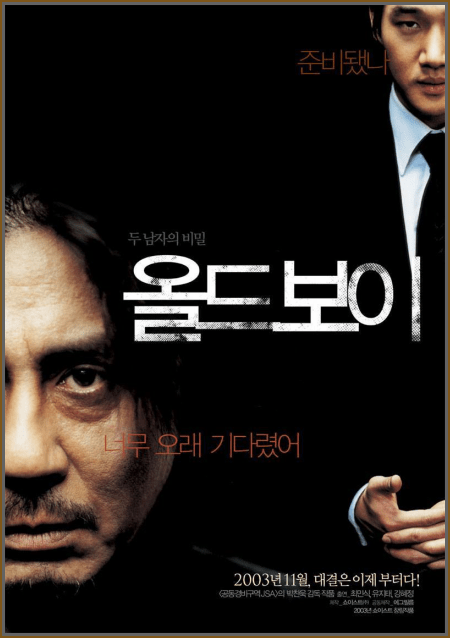

2003 would go down as the year a master filmmaker emerged from the ranks of the independent circles to the forefront of elite directors. Park Chan-wook was already well-known amongst the indie circuit as an innovative director coming out of South Korea’s burgeoning film industry. He’d already released such well-received films as Joint Security Area and Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. In fact, the film in question that’s propelled Mr. Park to the forefront would be the second part of a film trilogy dealing with the existential nature of vengeance and its effect on all involved. Oldboy follow’s Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance like a sonic boom and inproves on the first leg of the trilogy in every way.

Oldboy at its most basic is a revenge film. It is a film about a man wrongly and mysteriously imprisoned for reasons unknown to him and to the audience. We see Oh Dae-su — the man in question — through his 15 years of mysterious imprisonment and we see him change from the Average Joe from before his kidnapping to a taut, volatile and somewhat insane individual whose only goal in life is to find whoever did this to him and make him pay. Oh Dae-su’s imprisonment takes a good part in the telling and makes up the first third of the film’s tale. As the years go by we see him spiral down to the lowest depths a man can get to before sanity leaves him. There’s no evidence that he didn’t go insane during his imprisonment, but Park does show us scenes that Oh Dae-su’s singular focus to find out why he was imprisoned and to exact revenge on those involved might have just unhinged the poor man in the process.

The second part of the tale being told occurs the moment Oh Dae-su was suddenly — as mysteriously as his imprisonment — released. One moment he’s still in his prison where his only contact with the outside world is the TV in his room and then he’s on the rooftop of a building with new clothes on and a suitcase with more clothes and his notebooks where he’s listed all the names he thinks may have caused him this wrong. From here Dae-su goes on a whirlwind search to find clues and information on who may have imprisoned him. Along the way he meets the young sushi chef Mi-do who seem to have taken some interest in Oh Dae-su’s well-being and who slowly falls in love with him. It is their journey through the maze and labyrinth of false leads and trails that dominate the second third of this tale. It is also the part of the film where Oh Dae-su’s monster persona takes precedence as he wreaks havoc on anyone and everyone who may have the information he needs to solving the mystery of his imprisonment.

Many have already mentioned the wince inducing pliers scenes and the single-take corridor fight scene. But it is the lovemaking scene between Oh Dae-su and Mi-do that I consider the most pivotal scene of this part of the tale. With the two characters finally consummating their mutual attraction to each other we see the two as not separate entities but a singular one where both will reap whatever their search will sow in the end. Mi-do becomes less of a sidekick and more of an equal partner in Oh Dae-su’s search. She knows that the only way she and Dae-su would find true happiness together is if she helps him finish his quest even if it means finding the truth that may not be to their liking.

The third and final part of this tale finally puts to light just who exactly is the mastermind of all that has transpired. The clues picked up by Oh Dae-su starts to fall into place and the puzzle that opens up for him and the audience is nothing less than tragic and Shakespearean. This third part really hits the audience between the eyes about the nature of vengeance and how all-consumming it can be if allowed to simmer, grow and take root. We see how it has already driven Oh Dae-su to the brink of madness and how he teeters just beyond the point of no return. Then on the mastermind of the whole thing we see how one slip of the tongue in the distant past of all involved has consumed this individual to exacting a complex and appropriate plan of revenge on Oh Dae-su. As the tragic and heartwrenching final part of the tale weaves and continues to its conclusion no one ends up being the victor. All have become just the victim of the cycle of violence and vengeance thats taken hold of everyone.

Park Chan-wook’s direction was flawless and there’s not a wasted scene from beginning to end. Every scene was shot and edited with a sense of purpose to convey the mood and feel of the situation. It didn’t matter whether it was a a slower-paced scene where the actors conversed in intelligent dialogue or a scene full of frantic energy where burst of violence seemed both randomly shot but choreographed at the same time. The composition of the scenes and his judicious use of wide-angle and static shots with little editing helps convey the single-minded focus of Oh Dae-su and his main antagonist. Some of the scenes even show hints and clues to the audience that — as unlikely as it might seem — the whole film might be a figment of Oh Dae-su’s fractured mind as a consequence of his imprisonment. Park Chan-wook doesn’t answer whether it is a figment of Oh Dae-su’s imagination, but the theory is there for people to ponder over.

The screenplay written by Park from the original Japanese manga was excellent and doesn’t waste unnecessary exposition to distract the audience from the main tale being told. Everything said and acted on the screen ultimately leads to the shocking climax in the end. In fact, I would say that the climax of the film doesn’t happen until the very last second of the film before everything fades to black and the credits roll. That’s how tightly written and focused the screenplay was from beginning to end.

Then there’s the three main characters as played by Choi Min-sik , Yu Ji-tae , and Kang Hye-jeong. These three actors play their parts to perfection. Choi Min-sik as Dae-su Oh was a picture of focused madness. We invest in his quest for vengeance and as the final secret was unveiled we truly feel his shock, horror and anguish. Yu Ji-tae plays the mastermind of the whole thing with icy calculation. This was a man who had spent half his life working on, preparing and letting loose the events that would lead to him finally getting his revenge on Oh Dae-su. The two, though after the same goal of vengeance, are diametrically opposed in terms of look and personality. Then we have Kang Hye-jeong as Mi-do, the young sushi chef caught in the middle of this duelling vengeance tale. She was both endearing, innocent and the pure soul that keeps Oh Dae-su from spiralling into final madness. It truly becomes tragic that the final consequences of the vengeance wrought by both male principals impacts the female in the middle and in the end she remains oblivious to the truth and Kang Hye-jeong conveys this sincere, innocent naivete to sweet perfection.

There’s much more to say about Oldboy, but its really just more accolades to be heaped upon a near-perfect film. A film exploring the darker side of man’s inhumanity towards one another to satiate their self-righteous quest for so-called “justice” and retribution. Like Cronenberg’s A History of Violence, Park’s Oldboy also shows the unending cycle of vengeance heaped upon vengeance in addition to the violence it inherently breeds. Like Cronenberg’s 2005 film, Oldboy doesn’t fully answer this existential question but leaves it up to the viewer to make their own decision. Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy is a film that comes but once in an era and helps redefine an era of its place in film history. Oldboy also continues the vengeance trilogy with Sympathy for Lady Vengeance (shortened to just Lady Vengeance here in North America). Oldboy marks the true arrival of one of the new masters of film and he joins the fine company of such people as Scorcese, Cronenberg, and Kubrick. A near-perfect film all-around.