Raw Urgency and Psychological Horror in 28 Days Later

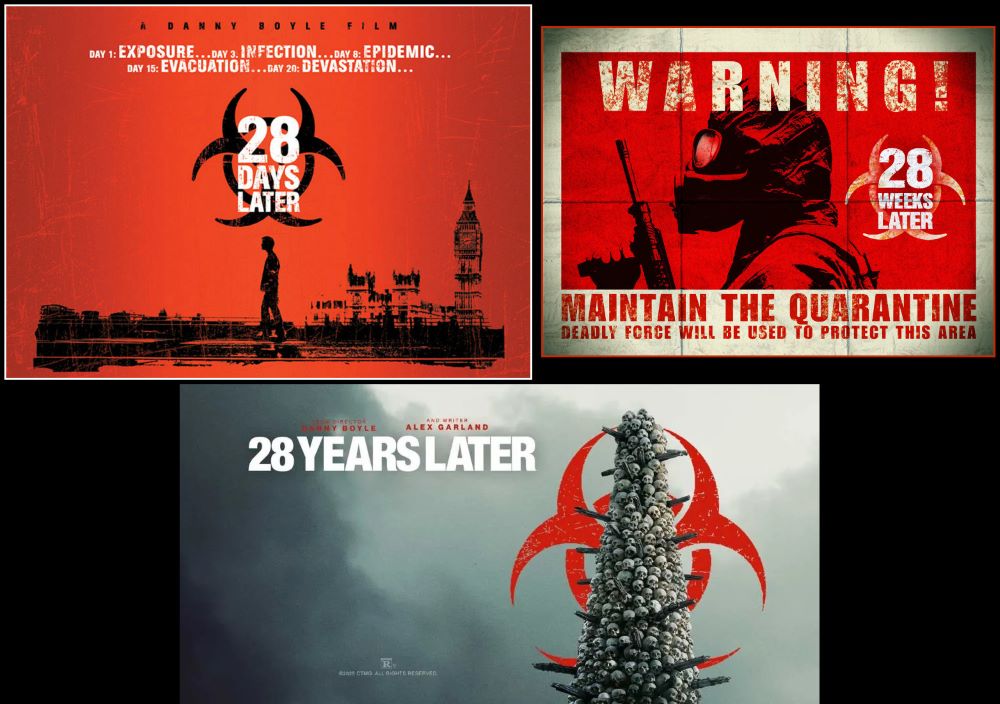

The original 28 Days Later broke new ground in horror filmmaking with its raw depiction of societal collapse fueled by a bioengineered rage virus. Danny Boyle and cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle’s decision to shoot on early digital video cameras gave the film a distinct grainy, handheld aesthetic that enhanced the feeling of immediacy and disorientation. This style was pivotal in immersing the audience in the eerie emptiness of a London ravaged by infection and abandonment. The stark realism allowed viewers to viscerally experience the isolation and relentless threat surrounding the protagonists.

Unlike traditional zombie films that relied on the supernatural or undead creatures, 28 Days Later introduced infected humans whose fast, uncontrollable aggression metaphorically represented not just a physical virus but the eruption of primal rage and societal breakdown. The tension escalates beyond the infected themselves, focusing sharply on human nature’s darker side through the militarized faction led by Major West, whose corruption and moral decay pose threats as dangerous as the virus itself. This potent blend of external horror and ethical decay elevated the film into a profound exploration of survival, despair, and moral ambiguity in post-apocalyptic conditions. The film resonated deeply with early 21st-century anxieties about sudden disaster and social breakdown, marking a revitalization of horror that has influenced countless works since.

Expansion and Escalation in 28 Weeks Later: A Cinematic Allegory of Its Time

Five years later, 28 Weeks Later expanded the series’ scope significantly. Director Juan Carlos Fresnadillo shifted the narrative from personal survival to the complexity of institutional attempts at restoring order. The film’s polished 35mm cinematography reflected its larger budget and ambition, with expansive urban destruction, dynamic action sequences, and a broader focus on systemic chaos. The narrative unfolds against the backdrop of a militarized “Green Zone” in London, an unmistakable cinematic parallel to the fortified American-controlled zone in Baghdad during the Iraq War.

This allegory extends beyond setting: it captures the tangled failures and ethical dilemmas inherent in the military occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan. The film’s military forces struggle to differentiate friend from foe, ally from insurgent, mirroring the real-world complexities and frequent tragic mistakes of those conflicts. The virus and subsequent resurgence symbolize not only physical contagion but institutional and social rot—highlighting how the rage of war, betrayal, and corruption can infect governance and community trust. The film’s grim depiction of fractured family relationships echoes a society strained by war and occupation, portraying how betrayal and mistrust pervade all levels of social interaction. Through this lens, 28 Weeks Later critiques the hubris of militarized control and the illusion of security, underscoring the fragile, often illusory nature of civilization under stress.

The film’s slicker, high-production-value style distances the viewer somewhat from the intimate immediacy of 28 Days Later but serves its themes by creating a sensation of broad and relentless turmoil. Thematically, this sequel embraces a darker cynicism by portraying militaristic and bureaucratic responses to crisis as part of the problem rather than the solution, intensifying the series’ meditation on rage to encompass political and social failure as well as personal violence.

Reflection and Maturation in 28 Years Later: Evolution of Horror, Philosophy, and a Pandemic Mirror

Returning to the director’s chair decades after the original, Danny Boyle’s 28 Years Later marks a tonal and stylistic evolution that reflects not only the temporal distance from the initial crisis but also a deepening philosophical introspection. The film depicts a Britain still struggling under the long shadow of trauma left by the rage virus. Its infected are no longer iconic red-eyed figures vomiting blood but more mutated, less defined threats, symbolic of how trauma itself can evolve into something less visible but more pervasive.

Cinematographically, 28 Years Later blends moody, shadowy aesthetics with intimate, often handheld shots. Notably, the production’s use of modern digital technology, including iPhone cameras, allowed the film to maintain an intimate feel despite technological shifts. This stylistic choice reflects the thematic focus on memory, decay, and fragile attempts at normalcy. The film’s visual language speaks to a world where the horrors of the past persist beneath the surface, influencing human behavior and societal structures.

Importantly, 28 Years Later serves as a cinematic allegory to the global COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. In interviews, both Boyle and Garland acknowledged how the experience of living through the COVID crisis deeply informed the film’s narrative and tone. The pandemic effectively turned empty urban landscapes and daily precautions—once confined to dystopian fiction like 28 Days Later—into real shared experience. The film’s story of a society struggling to live with the virus, navigating quarantine zones and adapting to endemic conditions, echoes how the world has contended with COVID-19’s ongoing impact. Themes of risk, resilience, and generational divide are foregrounded: characters grapple with what it means to live “28 years later,” taking long-term risks even as uncertainties remain. This mirror between fiction and reality deepens the film’s resonance, showing how past speculative fears have become present-day lived realities.

The tonal shift to a more contemplative and somber horror reflects how the pandemic shifted global consciousness from immediate crisis to endurance and adaptation. The film acknowledges grief, loss, and the cultural memory of lives disrupted and taken. Notably, a character’s act of creating memorials to victims reflects real-world efforts to remember those lost to COVID-19, underscoring cinema’s role in processing collective trauma. While this evolution away from pure terror to introspection divides audiences—some missing previous visceral scares—it represents a mature reckoning with the lasting scars pandemics imprint on humanity.

Pandemic Parallels: The Trilogy as a Cinematic Allegory for COVID-19 and Endemic Realities

While each film in the 28 Days Later trilogy originally reflected the anxieties and socio-political contexts of its own era, together they now resonate profoundly as a prophetic allegory of the global COVID-19 pandemic and humanity’s ongoing struggle to live with viral threats as part of everyday life. The trilogy’s trajectory—from sudden catastrophic outbreak to institutional collapse to long-term trauma and adaptation—mirrors the historical arc the world has experienced with COVID-19, offering viewers insight into the psychological, societal, and cultural impacts of pandemics.

28 Days Later anticipated much of the early pandemic experience—fear of rapid contagion, empty cityscapes, social disintegration, and the terrifying vulnerability of individuals isolated amid a global crisis. Jim’s awakening into an eerily deserted London strikingly parallels the empty streets during COVID lockdowns around the world, turning what was once dystopian fantasy into frightening reality. The film’s exploration of panic, isolation, and distrust toward institutions echoes widespread experiences of confusion, fear, and uncertainty during the first months of the pandemic when COVID-19 was unfamiliar, unpredictable, and devastating.

28 Weeks Later deepens this pandemic allegory by portraying the consequences of failed institutional responses and attempts at control. The militarized “Green Zone” concept eerily parallels the real-world challenges of creating “safe zones” amid outbreaks, with tensions between enforcement, mistrust, and community survival. The film’s depiction of fractured families and systemic collapse reflects how social solidarity frays under the pressure of prolonged crisis, political distrust, and ethical quandaries surrounding public health measures experienced globally during COVID waves. The allegory isn’t just about physical infection but social contagion—fear, misinformation, and political polarization as viral threats themselves.

With 28 Years Later, the trilogy fully embraces its role as a cultural mirror to COVID-19’s enduring legacy. Danny Boyle and Alex Garland have openly discussed how the realities of the pandemic shaped the film’s narrative and tone, with characters navigating life decades after the outbreak under quarantine and endemic conditions. The film presents a world where viral infection is an ongoing condition to be managed rather than eradicated, reflecting how many experts now view COVID-19’s transition from acute pandemic to endemic presence. This shift from immediate horror to long-term social and psychological adaptation speaks to the global experience of living alongside risk and uncertainty, balancing caution with the human drive to reconnect and rebuild.

Visual motifs such as quarantine zones, memorial walls, and generational divides throughout the film underscore real-world pandemic realities about loss, resilience, and the passing of collective trauma. The story’s focus on a new generation born into post-virus society echoes global concerns about children’s—educational, emotional, and social—impacts during and after COVID. The film’s meditative tone reflects the world’s evolving understanding that recovery from a pandemic is neither swift nor purely scientific but deeply human, requiring reckoning with grief, memory, and ethical questions about care and sacrifice.

Together, the trilogy transcends traditional horror storytelling to become a cinematic meditation on humanity’s confrontation with biological catastrophe—capturing the terror of sudden collapse, the anguish of institutional failure, and the fragile hope of enduring and adapting to an altered world. In doing so, the 28 Days Later series offers both a chilling warning and a compassionate reflection on survival in an age defined by viral uncertainty.

Stylistic Evolution: From Gritty Realism to Reflective Sophistication

The trilogy’s visual evolution is a testament to the shifting thematic priorities and growing artistic ambition of the filmmakers. 28 Days Later’s raw digital aesthetic—with grainy textures and handheld immediacy—rooted the audience in the chaos of sudden societal collapse, pioneering an immersive and tangible horror. The decision to film real, unpopulated London streets added an authentic eeriness that fueled the film’s power.

With 28 Weeks Later, the move to 35mm film signaled a turn toward cinematic polish, spectacle, and scope. The expansive shots, precise lighting, and dynamic action sequences reflect the film’s thematic scale, portraying systemic collapse and institutional failure with cinematic authority. The surveillance-like camerawork amplifies feelings of observation and control that echo its allegorical engagement with military occupation themes.

28 Years Later rebalances styles, fusing intimate handheld shots with shadowy, atmospheric imagery, aided by modern digital filmmaking tools including smartphone cameras. This blend cultivates mood and emotional depth over traditional jump scares, visually representing a society haunted by trauma and in cautious recovery. The stylistic shift underscores the trilogy’s journey from immediate survival panic to measured reflection on long-term consequences.

Thematic Progression and the Metaphor of Rage

Rage is the fundamental metaphor animating the trilogy, but its form and focus evolve significantly. In 28 Days Later, rage manifests as an explosive primal force embodied in the infected—visible, aggressive, and terrifying, stripping away thin veneers of civilization to reveal instinctual violence.

28 Weeks Later expands rage to include institutional rot, betrayal, and the failure of governance. The infected remain threats but rage’s more insidious expressions appear in military violence, political cynicism, and fracturing communities. Rage becomes a societal contagion undermining cohesion as thoroughly as any virus.

28 Years Later shifts to a metaphor of inherited trauma and enduring wounds. Rage here is less overt but deeper—passed through generations in memory, ethics, and societal dysfunction. The virus and its mutated infected echo how psychological and cultural trauma evolve and persist, questioning humanity’s capacity for healing or self-destruction.

Characters and Emotional Depth: From Intimate Survival to Generational Reckoning

Character arcs reflect this thematic evolution. 28 Days Later centers on individual survival and fragile relationships formed amid chaos. Jim’s transformation from bewildered victim to protector provides audiences emotional grounding in a shattered world.

28 Weeks Later explores family ruptures wrought by betrayal and trauma, mirroring broader social breakdowns. Characters’ struggle with trust and loss enriches the narrative with psychological realism.

28 Years Later depicts survivors burdened by collective memory and ethical dilemmas, often across generations. Its characters wrestle not only with the immediate horrors but with legacies of violence and the search for reconciliation, offering psychological and moral complexity rare in horror narratives.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

28 Days Later transformed horror by replacing slow, supernatural zombies with fast, rage-fueled infected who symbolize contemporary fears about sudden collapse and human savagery. It revitalized a moribund genre and influenced popular culture globally.

28 Weeks Later expanded on this foundation with action spectacle and socio-political allegory, polarizing audiences but enriching thematic depth, especially with its projection of military occupation anxieties.

28 Years Later confronts the real-world pandemic experience directly, integrating cultural trauma into its narrative and style. It challenges genre boundaries by emphasizing reflection and resilience over instant terror, heralding a new phase for horror cinema aware of global trauma.

The Future of the “28 Days Later” Series: Continuing the Journey

Building on the foundation of its groundbreaking predecessors, the “28 Days Later” series is set to continue with two more films that promise to expand its intricate narrative and thematic depth. 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, directed by Nia DaCosta and scripted by Alex Garland, is scheduled for release in January 2026. This film, shot back-to-back with 28 Years Later (2025), will deepen the post-apocalyptic exploration with returning characters and new threats, continuing the saga of trauma, survival, and societal collapse.

Additionally, a fifth film in the series is currently in development, though its title and release date remain unannounced. With Danny Boyle and Alex Garland involved in these projects, audiences can expect a thoughtful continuation that balances horror with reflective inquiry into humanity’s resilience. The return of Cillian Murphy as Jim further ties the new films to the series’ emotional origins, ensuring that the evolving mythology stays grounded in personal stakes.

As these future films approach, the 28 Days Later series remains ripe for ongoing critical and cultural re-examination, especially given its enduring power to mirror contemporary fears—from early 2000s anxieties to the global experience of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. The series stands as a dynamic, evolving reflection on rage, ruin, and the hope for redemption in an uncertain world.