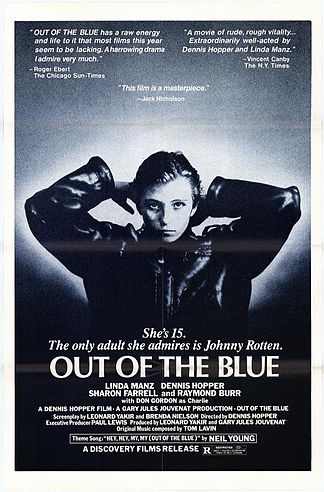

— Cebe (Linda Manz) in Out of the Blue (1980)

The 1980 Canadian film Out of the Blue opens with a terrifying scene. Don Barnes (Dennis Hopper), drinking a beer and playing with his daughter while driving a truck, crashes into a school bus. The bus is full of children, many of whom are seen being thrown into the air as the truck literally splits the bus in half.

Don is sent to prison. His wife, Kathy (Sharon Farrell), becomes a drug addict. His daughter, Cebe (Linda Manz), grows up to be an angry and alienated teenager. Cebe spends her time either aimlessly wandering around her economically depressed hometown or else ranting about the phoniness of society to anyone who will listen (and quite a few who won’t). Much like the killer cops in Magnum Force, all of her heroes are dead. Occasionally, she sees a pompous therapist (Raymond Burr) whose liberal humanism turns out to be just as empty as the reactionary society that Cebe is striking out against. Cebe’s heroes are Elvis, Sid Vicious, and her father.

When Don is finally released from prison, he returns home and he announces that he’s straightened out his life. He promises that he’ll stay sober and he’ll be a good father. That, of course, is all bullshit. Soon, Don is struggling to hold down a job and spending his time drinking with his friend Charlie (Don Gordon). Anyone who has ever had to deal with an alcoholic father will be able to painfully relate to the scenes where Don goes from being kind and loving to demonic in a matter of seconds.

Eventually, it all leads to a violent ending, one that is powerful precisely because it is so inevitable.

Out of the Blue is one of my favorite films, one that I relate to more than I really like to admit. Directed in a raw and uncompromising manner by Dennis Hopper, Out of the Blue is a look at life on the margins of society. And while some would argue that not much happens in the film between the explosive opening and the equally explosive ending, nothing needs to happen. The power of the film comes not from its plot and instead from the perfect performances of Linda Manz, Dennis Hopper, Sharon Farrell, and Don Gordon. Only Raymond Burr feels out of place but there’s a reason for that.

As much as I love Out of the Blue as a movie, I love the story of its production as well. Originally, Out of the Blue was to be your typical movie about a rebellious teen who is saved by a patient and compassionate counselor. Dennis Hopper was originally just supposed to co-star. However, after the shooting started to run behind schedule, the film’s original director was fired. Hopper talked the producers into letting him take over as a director.

This was the first film that Hopper was allowed to direct since the 1971 release of the infamous flop, The Last Movie. Hopper, who was then best known for his drug use and his alcoholism, promised to be on his best behavior. However, he then proceeded to secretly rewrite the entire film.

When Raymond Burr showed up to shoot his scenes, he was under the impression that he was still the star of the film. Hopper essentially proceeded to shoot two separate films. One film followed the original script and starred Raymond Burr. The other was Hopper’s vision. When it came time to take all of the footage and edit together the film that would be called Out of Blue, only two of Burr’s scenes made it into final cut and, in both of those scenes, Burr’s character is portrayed as being clueless.

Out of the Blue is not a happy film but it’s a good one. More people need to see it.