Note that this maybe a bit brief and off tangent. This may be one of the first reviews I’ve written for a film created well before my time. I won’t have as many movie references or personal anecdotes to add here.

I love the story of The Count of Monte Cristo. At the time of this writing, it can be found on both Amazon Prime and on Tubi.

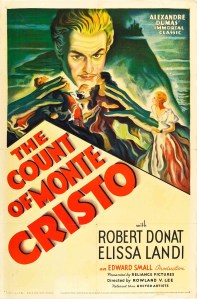

Written in 1844 by Alexandre Dumas, it’s a tale of revenge and depending on which version you watch, there’s also a bit of redemption to it. Though it’s adapted numerous times on stage and screen, I’m familiar with 3 main movie versions. You have the modern 2002 version from Kevin Reynolds, starring Jim Caviezel, Henry Cavill and Guy Pearce. There’s the 1975 TV Movie (my personal favorite), directed by David Greene and starring Richard Chamberlain, Donald Pleasance, Tony Curtis and Kate Nelligan. And finally, we have the classic 1934 rendition, directed by Donald V. Lee and starring Robert Donat, Elissa Landi, Sidney Blackmer and Louis Calhern. Most audiences may know of the film from the references made of it in 2005’s V for Vendetta.

The Count of Monte Cristo is the story of Edmund Dantes (Robert Donat, The 39 Steps) , a sailor who has everything going for him. He’s the newly minted Captain of the Pharaon, a title bestowed to him after the original captain died during a voyage near the island of Elba. Before the original Captain passes, he gives Edmond a letter to be delivered to an individual who will make himself known. This promotion and the letter also draws the jealous eyes of the would be Captain Danglars (Raymond Walburn, Christmas in July). Edmond has the heart of the lovely Mercedes de Rosas (Elissa Landi, The Yellow Ticket), but not the affections of Mercedes’ Mother (Georgia Caine, Remember the Night), the Madame de Rosas. Together with Fernand Mondego (Sidney Blackmer, Rosemary’s Baby), they often try to convince Mercedes to find someone better.

During the party for his wedding, Edmond meets the letter’s recipient and makes the delivery. Shortly afterward, both this man and Edmond are arrested. We learn the man is the father of The King’s Magistrate, Renee de DeVillefort (Louis Calhern, Julius Caesar). Choosing to protect his father (now considered a Bonapartist), DeVillfort puts on the blame on Dantes. With Mondego and Danglars as co-conspirators, they send Dantes to the dreaded Chateau D’if, an Alcatraz-like prison on the sea. To make things worse, after Napoleon is defeated, Edmond’s captors list him as deceased and his name is struck from the prison record. Dantes spends nearly 15 years in the Chateau, falling out of everyone’s memory. During his time, he discovers and befriends the Abbe Faria (O.P. Heggie, Anne of Green Gables), another prisoner who teaches Dantes various topics of the world. The Abbe also shares the secret of the De Sparda Treasure, hidden away just off the island of Monte Cristo. Edmond eventually escapes the Chateau D’If, acquires the treasure and returns to the Paris as the mysterious Count of Monte Cristo.

The film has fine performances throughout, given the time frame. Donat’s Dantes is quite naive prior to the imprisonment, but as the Count, I felt he brought a lot of style and class to the character. It was much like watching an old serial of The Batman or The Shadow. Another major surprise (for me, anyway) was Sidney Blackmer as Mondego. I’ve only ever seen Blackmer as the old and strange Roman Castavet in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary Baby, so it was very interesting to see him in his prime. There’s a nice duel between Mondego and Dantes that showcased Blackmer’s athleticism as well as his acting. I also enjoyed Walburn’s Danglars, who felt like a weasel you’d find in a classic Disney animated film.

Visually, for a black and white film, there’s some good use of light and shadow here, particularly during the dimly lit scenes in the Chateau D’If and the face off between the Count and Mondego.

How Edmond chooses to face his enemies was interesting. A bit of scandal for one, greed for another and a full-on courtroom drama for a third. I thought the court case element was bit much, but given where the story was going, it made sense. Overall, The Count of Monte Cristo is a wonderful classic with great pacing throughout.