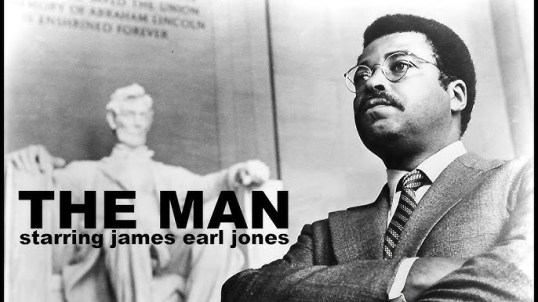

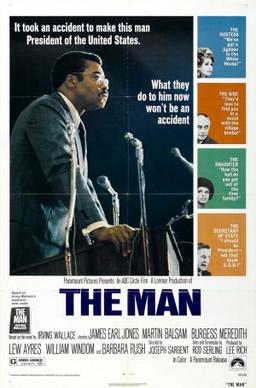

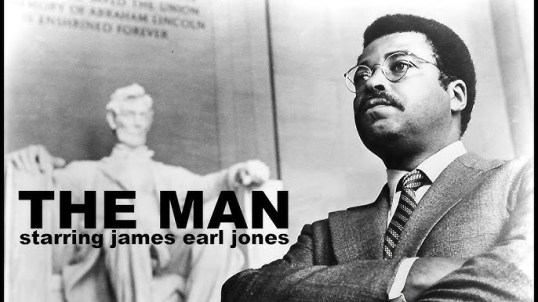

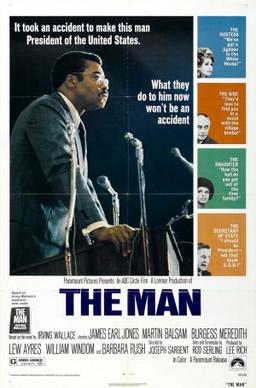

In 1972’s The Man, James Earl Jones stares as Douglass Dilman.

Dilman is a black college professor and a U.S. Senator. To his friends, he’s a symbol of progress. To his enemies, he’s a sell-out who is viewed as being improperly radical. The U.S. Senate, eager to prove that it’s not a racist institution, has elected Dilman as the President Pro Tempore. He is now fourth in line for the presidency but that doesn’t concern racist senators like Senator Watson (Burgess Meredith). A lot would have to happen before Dilman would ever become President.

Needless to say, a lot does happen.

The President and the third-in-line Speaker of the House are attending a conference at a historic building in Frankfort when the roof collapses on them. We don’t actually see this happen. We just hear the people in the White House talk about how it’s happened. We also don’t really learn many details about why the roof collapsed. Someone nonchalantly says, “It’s an old building.” Myself, I spent the entire movie waiting for some sort of big revelation of a conspiracy behind the roof collapse but it didn’t happen. Apparently, in 1972, the Secret Service just let the President go anywhere without checking the place out first. That said, it’s not a good thing when a serious movie opens with a dramatic plot development that, at the very least, draws a chuckle from the audience. Seriously, we lost our President because a roof fell on him? How is America ever going to live that down>

Vice President Noah Calvin (Lew Ayres) is wheeled into the White House cabinet room. This was not the first time that a Ayres played a Vice President called upon to succeed the President. Unlike in Advice and Consent, the Vice President announced that he cannot accept the honor of being sworn in because he’s too sick. (Since when does the Vice President have the option to refuse to do his Constitutional duty?) With Calvin putting the country ahead of his own ambition, Senator Watson announces that Secretary of State Eaton (William Windom) will be the new President. No, Eaton says, Dilman will be the new president. But once Dilman screws up and is either impeached or resigns, fifth-in-line Eaton will be sworn in.

Except …. it wouldn’t work that way. Excuse me while I put my history/political nerd hat on….

First off, Calvin is apparently still Vice President so if Dilman did step down, Calvin would once again be the successor. What if Calvin refused a second time? As soon as the Speaker of the House died, the House of Representatives would elect a new Speaker and that person would be third-in-line. And, as soon as Dilman became President, the Senate would elect a new President Pro Tempore and that person would be fourth-in-line. In other words, Eaton is no closer to being President than he was before.

My reason for going into all of this is to illustrate that The Man is a film about American politics that doesn’t really seem to know much about American politics. That said, it does feature the great James Earl Jones as Douglass Dilman and Jones gives such a good and thoughtful performance that it almost doesn’t matter that no one else in the film seems to be taking it all that seriously. Jones plays Dilman as being a careful and cautious man, one who understands that he occupies a huge place in history (Barack Obama was only 11 years old when this film came out) but whose main concern is just doing a good job as President. Dilman finds himself in the middle. On one side, he has advisors warning him not to scare America by being too radical. On the other side, his activist daughter (Janet MacLachlan) brands Dilman a sell-out. When a black student named Robert Wheeler (Georg Stanford Brown) is arrested for assassinating a South African government official, Dilman’s first instinct is to believe Wheeler’s been framed but, as the film progresses, doubts start to develop and Dilman must decide whether or not to risk an international incident. It’s an interesting story, well-played by James Earl Jones and Georg Stanford Brown.

It was originally mean to be a made-for-TV movie but, in order to capitalize on the excitement on the 1972 presidential election, it was released into theaters. As a result, the film often has the cheap look of a made-for-TV movie and quite a few members of the cast give performances that feel more appropriate for television than the big screen, (Some members of the cast, like Burgess Meredith, just overact with ferocious abandon.) In the end, The Man is mostly of interest from a historical point of view. (In 1972, the idea of a black man being elected President seemed so unrealistic that the movie actually had to drop the roof on 50% of the government just to get Dilman into the Oval Office.) James Earl Jones, who would have turned 94 today, is the main reason to watch.