“Stick to your plan. Anticipate, don’t improvise. Trust no one. Never yield an advantage. Fight only the battle you’re paid to fight. Forbid empathy. Empathy is weakness. Weakness is vulnerability.” — The Killer

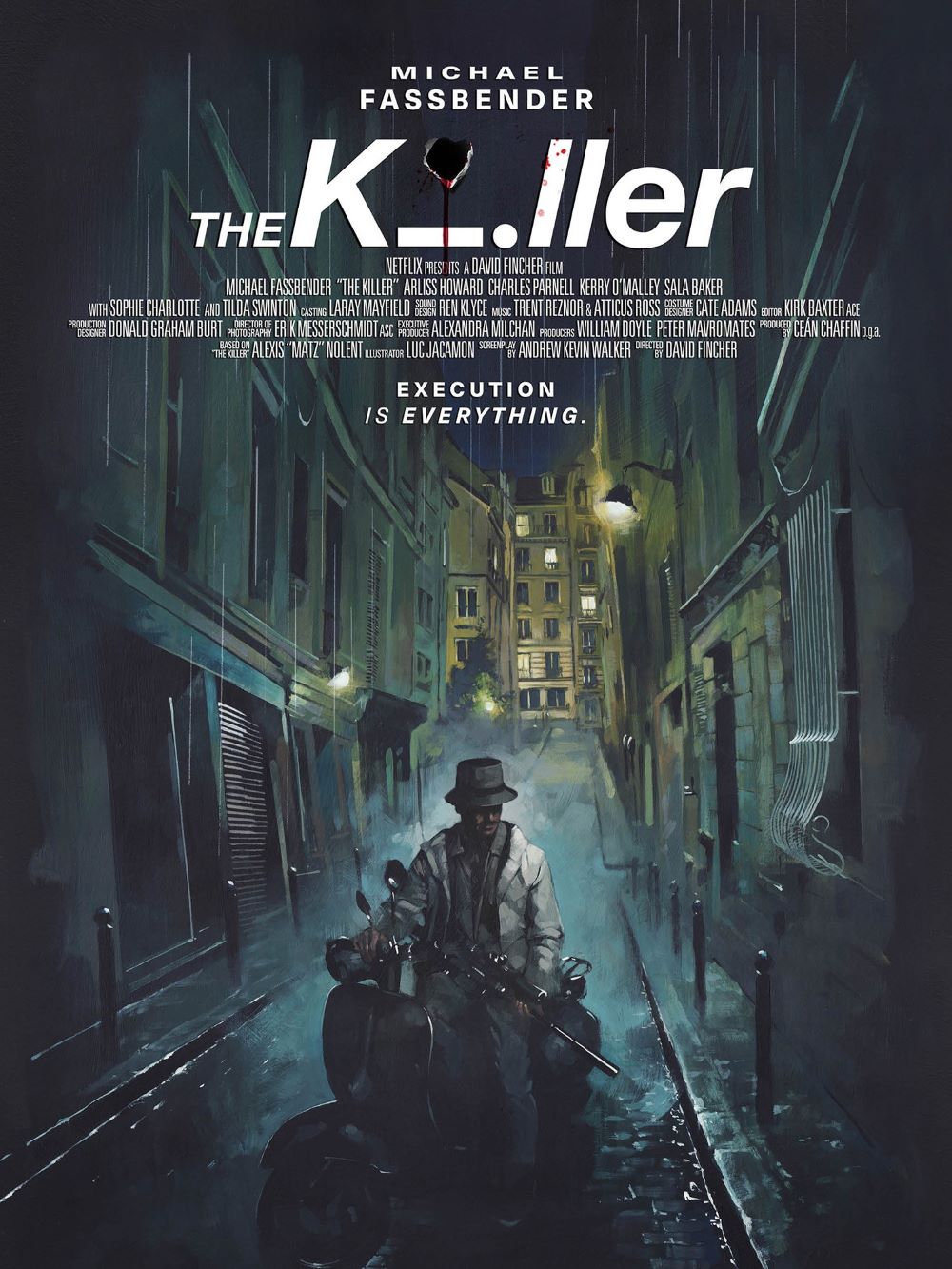

David Fincher’s The Killer lands like a perfectly aimed shot: clean, methodical, and laced with just enough twist to make you rethink the whole trajectory. At its core, the film follows an elite assassin—brilliantly played by Michael Fassbender—who suffers a rare professional failure during a high-stakes hit in Paris. After days of obsessive preparation in a WeWork cubicle, complete with hourly surveillance checks, yoga breaks, protein bar sustenance, and a nonstop loop of The Smiths, he pulls the trigger only to miss his target entirely.

This one slip shatters his world of ironclad redundancies and contingencies. Retaliation soon hits close to home, striking his secluded Dominican Republic hideout and drawing in his girlfriend. What begins as a routine job quickly escalates into a personal cleanup mission, spanning cities like New Orleans, Florida, New York, and Chicago. Fincher transforms these stops into taut, self-contained vignettes, layering precise bursts of violence over the protagonist’s gradual psychological fraying—all while keeping major reveals under wraps to maintain the film’s coiled tension.

The structure dovetails perfectly with Fassbender’s commanding performance. He embodies a man radiating icy zen on the surface, while a relentless machine churns underneath. His deadpan voiceover delivers self-imposed rules like a deranged productivity gospel—”forbid empathy,” “stick to your plan,” “anticipate, don’t improvise”—even as he slips seamlessly into civilian guises: faux-German tourist, unassuming janitor, casually ordering tactical gear from Amazon like it’s toothpaste.

The result is darkly hilarious, conjuring a corporate bro reborn as high-functioning sociopath, where bland covers clash absurdly with lethal intent. Yet as stakes mount, subtle cracks appear: split-second hesitations, flickers of unexpected mercy that betray buried humanity. Fassbender nails this evolution through sheer minimalism—piercing stares, economical gestures, weaponized silence—morphing the killer from untouchable elite into a flawed, expendable player in the gig economy’s brutal grind.

These nuances echo the film’s episodic blueprint, quintessential Fincher territory. On-screen city titles act as chapters in a shadowy assassin’s handbook, with tension simmering through drawn-out prep rituals: endless surveillance, gear assembly, contingency mapping that drags just enough to immerse you in the job’s soul-numbing tedium. The Paris mishap ignites the chase—he evades immediate pursuit, sheds evidence, and races home to fallout, then pursues leads through handlers, drivers, and rivals in a chain of escalating confrontations.

Fincher deploys action sparingly but with devastating impact. A standout brawl erupts in raw, prolonged chaos—captured in extended, crystal-clear shots with improvised weapons and no shaky-cam crutches—perfectly embodying the killer’s ethos even as it splinters around him. Each sequence builds without excess, from tense interrogations to standoffs that flip power dynamics, underscoring how the world’s rules bend unevenly.

This kinetic progression meshes flawlessly with Fincher’s visual command. Cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt crafts a hypnotic palette of cool desaturated blues, sterile symmetries, and digital hyper-reality, evoking unblinking surveillance feeds into an emotional void. Tactile details obsess: the rifle case’s satisfying zip, suppressed gunfire’s sharp snick, shadows creeping across WeWork pods, dingy motels, and gleaming penthouses—all mirroring the killer’s frantic grasp for order amid encroaching disarray.

Sound design heightens every layer, sharpening ambient clacks of keyboards, hallway breaths, and gravel footsteps to a razor’s edge. Integral to the immersion is the minimalist electronic score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, Fincher’s trusted collaborators from The Social Network to Mank. Their eerie ambient drones and ominous rhythmic pulses bubble like a suppressed heartbeat—swelling subtly in stakeouts, throbbing through violence, threading haunting motifs into voiceovers. It mirrors the protagonist’s inner turmoil without overwhelming the chill precision, turning silences between notes into weapons as potent as any sniper round.

This sonic and visual restraint powers the film’s bone-dry irony, which methodically punctures the protagonist’s god-complex. He preaches elite status among the “few” lording over the “many sheep,” yet reality paints him as sleep-deprived, rule-bending, and perpetually improvising—empathy leaking through denials in quiet, humanizing beats. Fincher weaves these into his signature obsessions—unmasked control freaks, dissected toxic masculinity, exposed capitalist churn—but with playful lightness, sidestepping the heavier preachiness of Fight Club or Seven.

The killer’s neurotic Smiths fixation injects quirky isolation amid globetrotting nomadism; their melancholic lyrics (“How Soon Is Now?”) punctuate stakeouts and flights like wry commentary on his fraying detachment. It all resolves in a low-key homecoming: no grand redemption or downfall, just weary acknowledgment that even “perfect” plans crack under chaos’s weight.

This sleight-of-hand elevates The Killer beyond standard assassin tropes into a sharp study of elite evil’s banality. Supporting roles deliver pitch-perfect economy: Tilda Swinton’s poised, lethal rival in mind-game restaurant tension; Arliss Howard’s obliviously entitled elite; Charles Parnell’s wearily betrayed handler; Kerry O’Malley’s poignant bargainer; Sala Baker’s raw, physical menace. Under two hours, Fincher packs density without bloat—layered subtext, rewatchable craft everywhere.

Gripes about its procedural chill or emotional distance miss the sleight entirely: this is a revenge thriller masking profound dissection of a borderless mercenary world, where pros prove as disposable as their untouchable clients. Fans of methodical slow-burns like Zodiac, The Game, or Gone Girl will devour the razor wit, process immersion, and unflinching thematic bite.

Ultimately, The Killer crystallizes as a sly late-period Fincher gem, fusing pitch-black humor, visceral horror, and surprising humanism into precision-engineered sleekness. It dismantles mastery illusions in unforgiving reality, leaving Fassbender’s killer stubbornly human: loose ends mostly tied, slipping back to obscurity as a survivor adapting. In a flood of bombastic action sludge, it offers bracing cerebral air—proving restraint, dark laughs, and surgical insight remain the filmmaker’s deadliest tools. For obsessive breakdowns of the human machine at its breaking point, it’s Netflix essential.