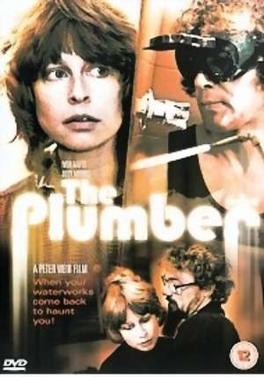

Peter Weir’s 1979 film, The Plumber, is essentially a battle of wills between two very different characters.

Jill Cowper (Judy Morris) is a masters student in anthropology. She’s educated, articulate, liberal-minded, and upper middle class. She’s married to Dr. Brian Cowper (Robert Coleby), a highly respected academic who is on the verge of being offered a position with the World Health Organization.

Max (Ivar Kants) is the plumber at the Cowpers’s building. We don’t find out much about his background, though it’s hinted that he’s had some previous trouble with the law. Max is friendly and talkative and, as soon becomes clear, amazingly determined. When he shows up at the Cowpers’s apartment, he tells Judy that he’s simply doing a check on all the building’s bathrooms. When Judy lets him in to do his inspection, Max announces that he needs to fix something with the plumbing. It should only take a day or two.

Except, of course, it takes more than a day or two. Max continually shows up at the apartment, usually waiting until Brian has left for the day. His comments to Jill become more and more intrusive and, whenever Jill takes offense, Max says that she’s misinterpreting him and that he’s just trying to be friendly. When Jill tells Brian that she thinks Max is intentionally destroying the plumbing so that he’ll have an excuse to be in the apartment, Brian refuses to believe her. When Jill tells her best friend, Meg (Candy Raymond), about what’s going on, Meg says that Max seems handsome and harmless.

Meanwhile, Max continues to work in the apartment’s bathroom, eventually turning it into a maze of pipes that seems to be constructed specifically to trap anyone unfortunate enough to enter the room….

The Plumber was originally made for Australian television. Though it was given a limited theatrical release in the United States (largely due to the arthouse success of Peter Weir’s previous films, The Last Wave and Picnic at Hanging Rock), The Plumber feels very much like a made-for-TV movie or perhaps an extended episode of an anthology series. It has a brisk 76-minute running time and visually, it features none of the striking imagery that one typically associates with Weir’s cinematic work. There’s no beautiful or majestic shots of the outback (like in Picnic at Hanging Rock) or the ocean (like in Master and Commander: Far Side of the World). Instead, the film takes place in the type of ugly and soulless cityscape that Harrison Ford was escaping from in Witness.

That said, The Plumber is still a memorable piece of work, one that feels perhaps more relevant today than when it was first released. Anyone who has ever dreaded having to take their car in for repairs or having to call someone out to fix an appliance will be able to relate to what Judy goes through with Max. The film is a reminder that, as much as we tell ourselves otherwise, we really are at the mercy of strangers. Judy may be better educated than Max and she may have more money than Max but what she doesn’t have, at least until the end of the film, is Max’s animal cunning. Max knows exactly what to say to get inside of the apartment and, once he’s inside, he knows exactly what to do to make it impossible for Judy to keep him from returning.

As upsetting as Max’s actions are, what’s even more upsetting is how everyone refuses to believe Judy when she tries to tell them what’s going on. Judy is told she is overreacting. Judy is told that she just doesn’t understand how these things work. Max gets offended that Judy doesn’t appreciate all of the hard work that he’s doing for her, despite the fact that she never asked him to do any of it. He does everything short of telling her that she needs to smile more. He’s the ultimate toxic presence, invading Judy’s life and refusing to leave. Everyone has had to deal with a Max but, for women, he’s an especially familiar and loathsome figure. The film may have clearly been made for Australian television but its themes are universal.

Because almost all of the action takes place in one small apartment, The Plumber is undeniably stagey. (It’s easy to imagine it as being a two-act play.) However, it’s also very well-acted and occasionally even darkly humorous. (As loathsome as Max is, it’s hard not to laugh a little when you see the maze of pipes he’s constructed in the bathroom.) It occasionally shows up on TCM so keep an eye out.