“If it’s transgressive, addressing social or political ills, not pulling punches, and pushing the boundaries, then it’s Splatterpunk.” — Brian Keene

The Birth of Splatterpunk: A Rebellion Against Conventions

To understand splatterpunk, it’s important to grasp the context in which it arose. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, horror fiction was often pigeonholed within predictable tropes—haunted houses, vengeful spirits, and formulaic slasher stories. While these were popular, they had limited scope in pushing the boundaries of what horror might represent. Enter splatterpunk—a raw, unapologetic literary movement that sought to shatter expectations by depicting violence, depravity, and, crucially, sexual violence unmasked. Rather than hinting at horrors lurking in the shadows, splatterpunk authors chose to parade these monstrosities in graphic detail.

The term “splatterpunk” was adopted by writer David J. Schow during the 1986 Twelfth World Fantasy Convention, encapsulating the aesthetic of horror tales that embraced hyper-intense gore, moral extremity, and the inclusion of sexual violence as a core and unsettling element. But it is crucial to recognize that splatterpunk is much more than explicit depictions of blood and guts or sexual assault. At its core, it serves as a mirror reflecting society’s darkest anxieties—whether those arise from political corruption, existential dread, psychological disintegration, or the breakdown of human decency. The shock of violence and abuse serves a purpose beyond mere thrill—it demands readers confront the ugliness beneath civilization’s polished surface.

Philip Nutman’s Wet Work: Fusion of Espionage, Cosmic Horror, and Splatter

A prime example of splatterpunk’s genre-blurring capacity is Philip Nutman’s Wet Work (1993), a work that may be less known outside hardcore horror circles but exemplifies the subgenre’s versatility. What sets Wet Work apart is its remarkable weaving of government espionage thriller with apocalyptic zombie horror and an infusion of cosmic dread.

Originally appearing as a short story in the seminal 1989 collection Book of the Dead, Wet Work expanded into a novel that follows CIA operative Dominic Corvino and Washington D.C. cop Nick Packard as they navigate the chaos unleashed when a comet named Saracen passes close to Earth. The comet deposits a mysterious residue that triggers the rise of the dead, but Nutman’s zombies are not mere shambling corpses—they retain fragments of cognition, making them unpredictable threats.

What makes Wet Work an intriguing splatterpunk novel is how it weds the procedural authenticity of espionage with the surrealism of the undead outbreak. Nutman’s background as a journalist and film critic manifests in the meticulous detail of military operations, CIA bureaucracy, and police procedures, lending credibility even amid the nightmare. The narrative unfolds on two interwoven axes: Corvino’s obsessive quest to uncover betrayal within the CIA and Packard’s desperate, grounded attempts to save his wife amid an escalating societal breakdown.

Nutman’s writing style embodies splatterpunk’s hallmark—graphic, fast-moving, and unapologetically violent—while resisting descent into parody. The horror and violence, including underlying currents of sexual violence and abuse within the collapsing societal order, are not gratuitous but rather emphasize the erosion of social and moral codes. Unlike some zombie fiction limited to straightforward survival stories, Wet Work interrogates themes of loyalty, obsession, power, and the devastating consequences of moral decay when survival becomes personal.

Kathe Koja’s The Cipher: Psychological Abyss and Cosmic Terror

While Nutman’s warm-blooded action situates Wet Work within both thriller and horror traditions, Kathe Koja’s The Cipher (1991) takes splatterpunk into the realms of psychological fragmentation and cosmic existentialism. The Cipher is notable for its uncompromising dive into emotional and metaphysical abyss, presented through an experimental, impressionistic narrative voice that eschews linearity in favor of portraying the chaotic consciousness of protagonist Nicholas.

The story revolves around Nicholas and Nakota in a bleak urban environment, where they discover the Funhole—a nightmarish, reality-bending void with an unknowable malignance. Rather than external monsters, the book’s terror arises from the characters’ psychological unraveling, toxic relationships, and the Funhole’s corruptive influence. Koja’s prose often unfolds in long, surreal sentences that immerse readers in impressions, hallucinations, and emotional storms, demanding patience and openness to ambiguity.

This approach challenges traditional horror expectations by prioritizing atmosphere and mental disintegration over plot-driven scares. The horror here is symbolic and metaphysical—body horror and reality distortions become reflections of inner fragmentation and humanity’s insignificance before cosmic forces. While the novel largely focuses on psychological and existential themes, it does not shy away from portraying abusive and toxic dynamics, including sexual violence, as instruments of psychological torment and character breakdown. The Cipher’s bleak, ambiguous ending refuses comfort, emphasizing oppression, transformation, and loss, resonating profoundly with readers attuned to introspective and literary horror.

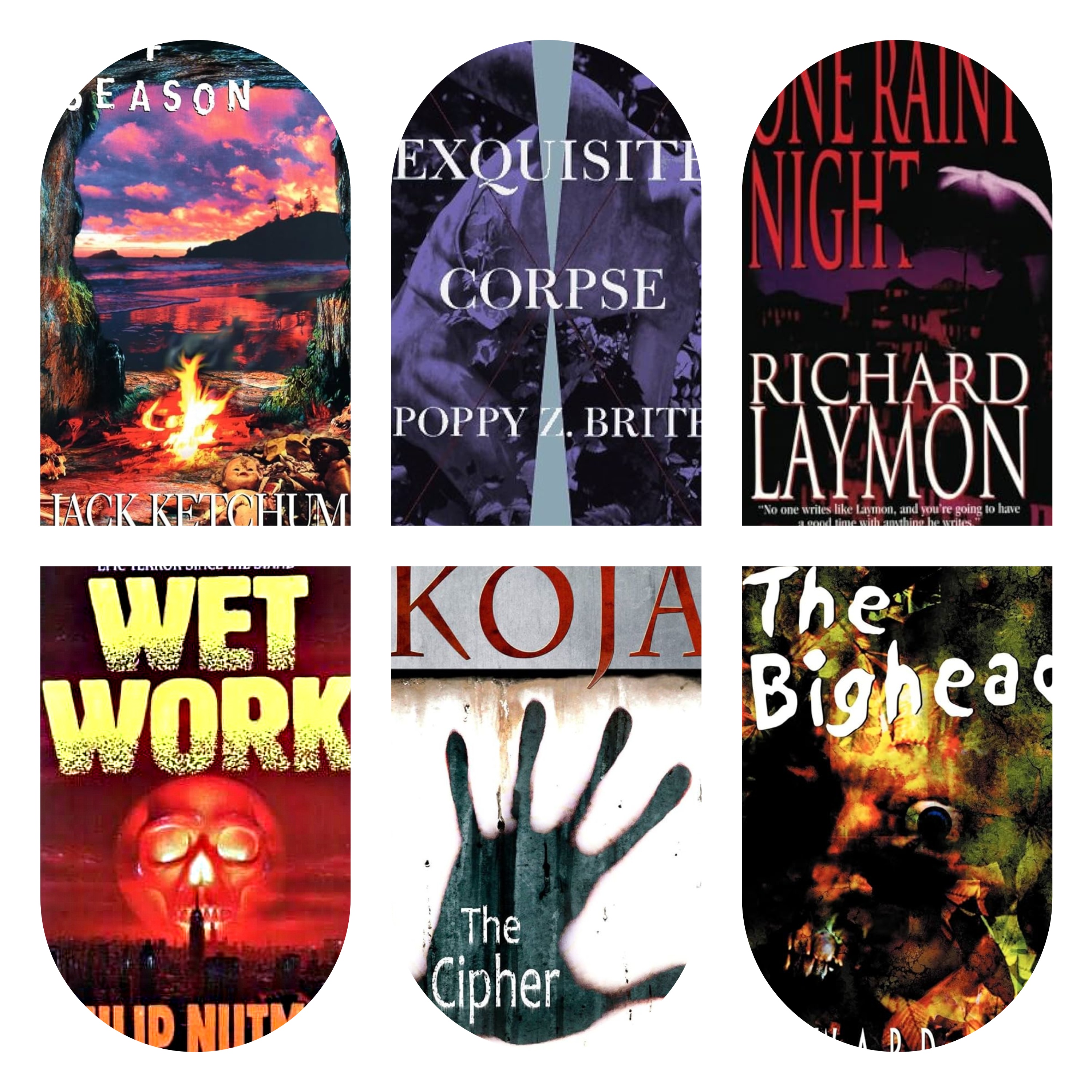

Jack Ketchum’s Off Season: Raw Human Horror and Primal Survival

In sharp contrast to Koja’s cerebral horror and Nutman’s hybrid apocalypse thriller is Jack Ketchum’s Off Season (1980), a foundational extreme horror novel that sinks its teeth into primal human savagery stripped of supernatural mediations. Loosely inspired by the legend of the Sawney Beane clan, Ketchum sets his story on the rugged Maine coast, depicting a group of urban friends facing a secluded clan of cannibals.

Off Season is known for its relentless pace and unapologetic portrayal of violence, sexuality, and survival instinct. Sexual violence and abuse permeate the narrative, presented in stark, unvarnished terms that are deeply disturbing yet integral to Ketchum’s exploration of human depravity. The horror stems from the inhumanity of other humans—feral descendants who embody basic drives like hunger, reproduction, and dominance without societal filters. Ketchum’s refusal to soften or sensationalize the unfolding carnage demands readers confront uncomfortable truths about violence, both physical and sexual, and regression. The victims are archetypal rather than deeply individualized, serving as symbolic representations of civilization confronting its darkest, hidden counterparts.

What sets Off Season apart is the absence of cathartic justice or narrative redemption. Survivors escape, but at immense psychological and physical cost, emphasizing that some horrors leave permanent scars rather than neatly tied endings. It is this brutal honesty—depicting horror not as spectacle but as unavoidable consequence—that cements Off Season’s legacy in splatterpunk and extreme horror.

The Broader Splatterpunk Landscape: Barker, Lee, Laymon, and Martin (aka Poppy Z. Brite)

A key progenitor of the splatterpunk aesthetic, Clive Barker’s Books of Blood (mid-1980s) was revolutionary in merging graphic, visceral horror with a literary sensibility that incorporated elements of dark fantasy and eroticism. Barker’s stories broke new ground by combining vivid, often grotesque imagery with profound explorations of human desire, morality, and the otherworldly. Sexual violence and transgressive sexuality appear throughout his work, often complicating the boundary between beauty and horror. In particular, Barker’s exploration of the sacred versus the profane is central, as the presence of sexual violence disrupts conventional moral frameworks and questions the nature of sin and desire. The collection’s influence was far-reaching, paving the way for horror fiction to be taken seriously as an art form capable of grappling with complex themes while delivering shocking, unforgettable scenes. Barker’s ability to balance poetic language with unsettling gore worked as a blueprint for many splatterpunk writers seeking depth beyond surface violence.

Edward Lee’s The Bighead epitomizes the extreme end of splatterpunk, reveling in unapologetically explicit violence, taboo subjects, and shock value. Lee’s storytelling mixes horror with dark humor and nihilism, pushing the boundaries of taste to explore the grotesque and the absurd. Sexual violence in Lee’s work is frequently explicit and controversial, serving to amplify the transgressive nature of his narratives. Furthermore, Lee uses sexual violence and deviancy as a way to examine the tension between the sacred and the profane—the clash between deeply ingrained cultural taboos and destructive carnal impulses. Though considered excessive by some, Lee’s books embody splatterpunk’s ethos of confronting the reader head-on with chaos and depravity. His work fuses visceral physical horror with nihilistic philosophical darkness, reflecting a world stripped of hope and full of monstrous extremes.

Richard Laymon’s One Rainy Night is notable for its blend of fast-paced plotting, graphic sexual and violent content, and elements of supernatural and psychological horror. Laymon’s work embodies a consistent use of sexual violence intertwined with sexual themes as part of the horror fabric, challenging readers with uncomfortable depictions of human depravity. His skillful pacing ensures that tension remains high, and his writing frequently navigates the intersection of splatterpunk gore with thrilling, page-turning storytelling. While his characters may sometimes function more as archetypes than fully nuanced figures, their plight against overwhelming horror rings true. Laymon’s stories helped solidify splatterpunk’s presence in mainstream horror by offering stories that are simultaneously intense, accessible, and relentlessly engaging.

William Joseph Martin (aka Poppy Z. Brite) stands apart for his elegant prose style and his exploration of identity, marginalization, and monstrosity through the lens of serial killers and dark romance. Martin (writing as Poppy Z. Brite) intertwines graphic violence with themes of homosexuality, queer identity, and sexual violence, challenging readers to consider the humanity amidst monstrosity. In doing so, Exquisite Corpse broadens splatterpunk’s thematic horizons, underscoring that horror’s most compelling stories often arise from complex characters whose transgressions are inseparable from their search for connection and self-understanding. Sexual violence in Martin’s work adds layers of suffering and violation that complicate the depiction of desire and identity, highlighting the fragile line between victim and monster. Martin’s fusion of stylistic beauty and bleak content enriches the genre’s emotional and intellectual depth.

Legacy and Impact of Splatterpunk Horror

A lasting impact of splatterpunk is evident in its refusal to compromise aesthetics for shock alone. Although its extreme visuals, sexual violence, and brutal thematic content led to limited mainstream acceptance, the genre’s influence persists. It demonstrated convincingly that graphic violence and sexual transgression could serve as a lens for social critique, psychological depth, and genre innovation. Works such as Wet Work exemplify its capacity for genre-blending; The Cipher exemplifies its introspective and cosmic depths; Off Season encapsulates its primal, uncompromising core. These stories continue to inspire writers who wish to push original boundaries, reshaping horror into a form that is as intellectually challenging as it is viscerally shocking.

Horror’s landscape has been irrevocably altered by splatterpunk. Its legacy persists not merely through the continued production of extreme horror but through its foundational principle—that horror is most potent when it does not flinch from the evils and truths of the human condition, including the often difficult subject of sexual violence. Its influence endures in the modern works that blend visceral impact with thematic richness, ensuring that horror remains a vital, evolving art form capable of confronting the darkest facets of existence while challenging cultural limits.

In embracing the fights, fears, and horrors that many shy away from, splatterpunk proves to be more than just a genre—it’s a bold call to confront the uncomfortable, an invitation to see horror not only as entertainment but as a mirror of our deepest truths. Its legacy remains a testament to the power of extremity paired with insight, forever pushing the boundaries of what horror can and should be.