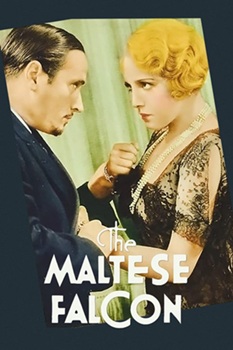

Detective Sam Spade (Ricardo Cortez) may be an immoral lech but when his partner, Miles Archer, is murdered, Sam sets out to not only figure out who did it but to also eliminate himself as a suspect. Sam was having an affair with Miles’s wife, Ivy (Thelma Todd). Sam’s investigation leads to him falling for the mysterious Miss Wonderly (Bebe Daniels) and getting involved with a trio of flamboyant criminals who are searching for a famous relic, the Maltese Falcon. Dudley Digges plays Casper Gutman. Otto Matieson plays Dr. Joel Cairo. Dwight Frye plays the gunsel, Wilmer, who Gutman says he “loves … like a son.”

Detective Sam Spade (Ricardo Cortez) may be an immoral lech but when his partner, Miles Archer, is murdered, Sam sets out to not only figure out who did it but to also eliminate himself as a suspect. Sam was having an affair with Miles’s wife, Ivy (Thelma Todd). Sam’s investigation leads to him falling for the mysterious Miss Wonderly (Bebe Daniels) and getting involved with a trio of flamboyant criminals who are searching for a famous relic, the Maltese Falcon. Dudley Digges plays Casper Gutman. Otto Matieson plays Dr. Joel Cairo. Dwight Frye plays the gunsel, Wilmer, who Gutman says he “loves … like a son.”

The first film adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s classic detective novel is overshadowed by the version that John Huston would direct ten years later. That’s not surprising. There’s a lot of good things about the first version but it’s never as lively than John Huston’s version and neither Dudley Digges nor Otto Matieson can compare to Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre. Of the supporting cast, Dwight Frye makes the best impression as the twitchy Wilmer and Bebe Daniels and Thelma Todd are both sexy as the story’s femme fatales. That doesn’t mean that they’re better than their counterparts in John Huston’s film. It just means they all bring a different energy to their roles and it’s interesting to see how the same story can be changed by just taking a slightly different approach. Elisha Cook, Jr. was perfect for Huston’s version of the story. Dwight Frye is similarly perfect for Roy Del Ruth’s version.

Needless to say, Ricardo Cortez can’t really compare to Humphrey Bogart. But, if you can somehow block the memory of Bogart in the role from your mind, Cortez actually does give a good performance as Spade. Because this was a pre-code film, Cortez can lean more into Spade’s sleaziness than Bogart could. Also, because this was a pre-code film, the first Maltese Falcon doesn’t have to be as circumspect about the story’s subtext. Spade obviously tries to sleep with every woman he meets and is first seen letting a woman out of his office. (The woman stops to straighten her stockings.) Gutman and Cairo’s relationship with Wilmer becomes much more obvious as well. What’s strange is that, even though this Maltese Falcon is pre-code, it still ends with the type of ending that you would expect the production code to force onto a film like this.

If you’re going to watch The Maltese Falcon, the Huston version is the one to go with. But the first version isn’t bad and it’s worth watching for comparison.