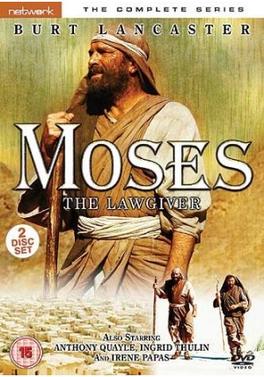

I should probably start this review by admitting that there’s a legitimate question concerning whether or not 1974’s Moses, the Law-Giver should be considered a film or a miniseries. Though there was an edited version of Moses that ran for 141 minutes and which was apparently released in theaters, the unedited version of Moses is 300 minutes long and was broadcast on television over a period of 6 nights. The long, unedited version is the one that I watched on Prime for five hours on Friday. Having watched the entire thing in one sitting, I personally consider Moses, the Law-Giver to be a film, albeit a very long one.

Moses, The Law-Giver tells the story of Moses and how he was exiled from Egypt, just to return years later to demand that Pharaoh set his people free. The first two and a half hours deal with Moses and Egypt. The second half of the film follows Moses and the Israelites as they seek the Promised Land. Moses covers the same basic ground as The Ten Commandments, just in a far less flamboyant manner.

For instance, Charlton Heston was a powerful and fearsome Moses in The Ten Commandments. In Moses, the Law-Giver, Burt Lancaster is a bit more subdued in the lead role. Even though Lancaster was far too old to play the role, he still gives a convincing performance. He plays Moses as a man who starts out unsure of himself but who grows more confident as the journey continues. He’s also a man who is constantly struggling to control his emotions because he knows that he doesn’t have the luxury of showing any sign of weakness. Whereas Heston bellowed in rage at the sight of the Golden Calf, Lancaster comes across more like a very disappointed father who is about to ground his children. Lancaster’s low-key performance pays when, towards the end of the film, Moses is told that he will see the Promised Land but that he will not enter it. The sudden look of pain on Moses’s face is powerful specifically because we’ve gotten so used to him holding it all back. For a brief moment, he drops his mask and we realize the toll that the years have taken on him.

In The Ten Commandments, Yul Brynner was a determined and arrogant Pharaoh. In Moses, the Pharaoh (who is played by Laurent Terzieff) is far more neurotic. He’s portrayed as being Moses’s younger cousin and he seems to be personally hurt but Moses’s demand that the slaves be granted freedom. It creates an interesting dynamic between the two characters, though it also robs the film of a credible villain. Whereas Brynner’s Pharaoh was a fearsome opponent, Terzieff plays the character as being weak and indecisive. Even if one didn’t already know the story, it’s till impossible to be surprised when Terzieff finally relents and allows the Israelites to leave Egypt.

Most importantly, Moses, The Law-Giver devotes more time to the relationship between Aaron and Moses than The Ten Commandments does. In The Ten Commandments, John Carradine’s Aaron was an often forgotten bystander. In Moses, Anthony Quayle plays Aaron and he’s pretty much a co-lead with Lancaster. The film is as much about Aaron as it is about Moses and it actually takes the time to try to logically develop how Aaron could have been duped into creating the Golden Calf. Quayle gives the best and most compelling performance in Moses, playing Aaron as a well-meaning and loyal sibling who, unfortunately, is often too worried about keeping everyone happy. For all of his loyalty to Moses, Aaron still struggles with feelings of envy and Quayle does a wonderful job portraying him and turning him into a relatable character.

As a film, Moses, The Law-Giver is never as much as fun as The Ten Commandments. It’s almost too subdued for its own good. On the one hand, it’s possible to appreciate Moses for taking a somewhat realistic approach to the story but …. well, is that really what we want? Or do we want the spectacle of decadent Egypt and the excitement of the red sea crashing down on Pharaoh’s army? You can probably guess where I come down on that.

Of note to fans of Italian cinema, the film’s score — which is pretty good — was composed by Ennio Morricone. The film’s special effects are credited to none other than Mario Bava! This was one of Bava’s final credits. Unfortunately, the special effects are never really that spectacular and there’s a few scenes where it’s obvious that stock footage has rather awkwardly been utilized. But, no matter! It still made me happy to see Bava’s name listed in the end credits.

Moses, The Law-Giver has its moments but, ultimately, The Ten Commandments remains the Moses film to watch.