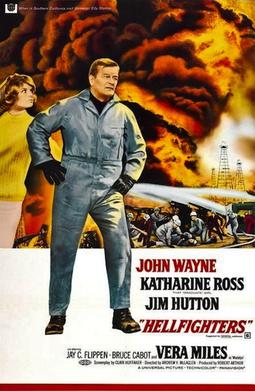

Chance Buckman (John Wayne) is the best there is when it comes to fighting oil fires. Along with Greg Parker (Jim Hutton), Joe Horn (Bruce Cabot), and George Harris (Edward Faulkner), Chance travels the world and puts out fires that the regular authorities can’t handle. Chance loves his job but he also loves his ex-wife, Madelyn (Vera Miles). When Madelyn indicates that she wants to remarry Chance but only if he pursues a less dangerous line of work, Chance retires from firefighting and becomes an oil executive. He leaves his firefighting company to his new son-in-law, Greg. When Greg and Chance’s daughter (Katharine Ross) head down to Venezuela to battle a fire and find themselves not only having to deal with the flames but also with a band of revolutionaries, Chance is the only one who can help them.

Chance Buckman (John Wayne) is the best there is when it comes to fighting oil fires. Along with Greg Parker (Jim Hutton), Joe Horn (Bruce Cabot), and George Harris (Edward Faulkner), Chance travels the world and puts out fires that the regular authorities can’t handle. Chance loves his job but he also loves his ex-wife, Madelyn (Vera Miles). When Madelyn indicates that she wants to remarry Chance but only if he pursues a less dangerous line of work, Chance retires from firefighting and becomes an oil executive. He leaves his firefighting company to his new son-in-law, Greg. When Greg and Chance’s daughter (Katharine Ross) head down to Venezuela to battle a fire and find themselves not only having to deal with the flames but also with a band of revolutionaries, Chance is the only one who can help them.

When I was growing up, Hellfighters was one of those movies that seemed to turn up on the local stations a lot. The commercials always emphasized the idea of John Wayne almost single-handedly fighting fires and made it seem as if the entire movie was just the Duke staring into the flames with that, “Don’t even try it, you SOB” look on his face. As a result, the sight of John Wayne surrounded by a wall of fire is one of the defining images of my childhood, even though I didn’t actually watch all the way through until recently. When I did watch it, I discovered that Hellfighters was actually a domestic drama, with an aging Wayne passing the torch to youngster Jim Hutton but then taking it back.

The fire scenes are the best part of Hellfighters and I wish there had been more of them. The movie gets bogged down with all of Chance’s family dramas but it comes alive again as soon as John Wayne and his crew are in the middle of a raging inferno, putting their lives at risk to try to tame the fire. Wayne was always at his best when he was playing strong, no-nonsense men who were the best at what they did. Hellfighters is slow in spots but the fire scenes hold up well. There’s no one I’d rather follow into an inferno than Chance Buckman.