“I mean, in a sense we’re all vampires. We drain energy from other life forms. The difference is one of degree. That girl was no girl. She’s totally alien to this planet and our life form… and totally dangerous.” — Dr. Hans Fallada

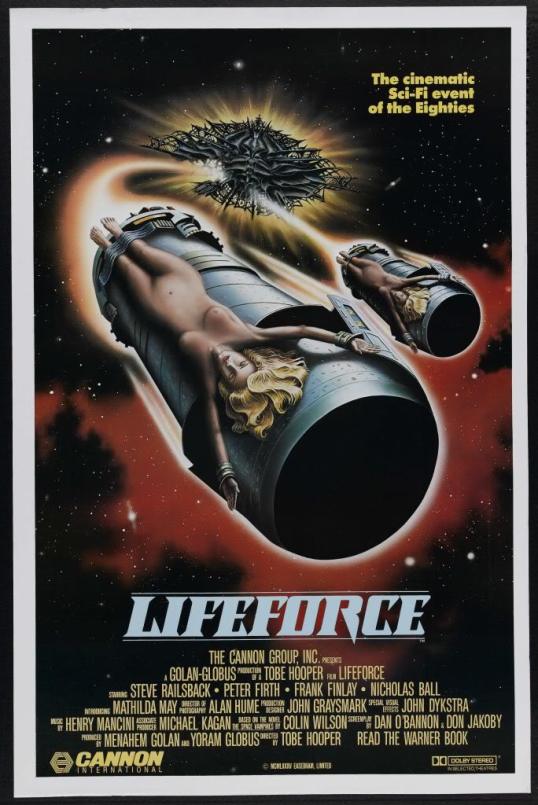

1985’s Lifeforce, directed by Tobe Hooper, was critically panned and barely registered at the box office. Yet in the decades since its release, something curious has happened: the film has gathered a loyal cult following among fans of science fiction and horror. Hooper’s film fuses so many genre conventions that it resists classification—too strange for pure sci-fi, too grandiose for standard horror. The result is a striking and eccentric reinvention of the vampire myth, a lavish but uncanny blockbuster that feels imported from an alternate cinematic timeline.

The film begins squarely in the realm of science fiction. Conceived during the public fascination with Halley’s Comet ahead of its 1986 return, Lifeforce rode the wave of comet-themed media flooding the decade. Most were cheap cash-ins. Hooper’s film stood out for its ambition and its visual scale.

Coming off Poltergeist, Hooper received an unusually large budget—a far cry from the lean, feral energy of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The story follows the crew of the shuttle Churchill as they discover a massive alien spacecraft hidden in the comet’s tail. Inside, frozen in suspended animation, are three humanoid figures. The ship’s dignified name feels ironic, even doomed; considering what’s to come, Demeter might have been more fitting. Like the sailors of Stoker’s novel, these astronauts inadvertently ferry an ancient predatory force home—yet this time, the threat arrives from the stars.

The horror unfolds once the crew retrieves its mysterious “specimens.” Members die in gruesome succession until only one survivor, Colonel Tom Carlsen (Steve Railsback), escapes in a pod back to Earth. Railsback’s performance is an intriguing mix of unhinged emotion and grim conviction. His intensity suits a film that constantly walks the line between pulp spectacle and cosmic tragedy.

When the story shifts to London, Lifeforce transforms into a supernatural thriller with procedural undertones. Peter Firth’s Colonel Colin Caine becomes the viewer’s compass: calm, authoritative, and determined to impose order on mounting chaos. As London succumbs to panic and outbreak, his steady professionalism anchors the outlandish events. His partnership with Railsback’s haunted, psychic Carlsen gives the middle act its volatile energy.

Among the supporting cast, Frank Finlay leaves one of the strongest impressions as Dr. Hans Fallada, a scientist fascinated by death and metaphysical energy. He serves as both philosopher and investigator, treating the vampiric invasion as a riddle of life itself. His restrained curiosity lends weight to scenes that might otherwise descend into absurdity. While the city collapses, Fallada studies the phenomenon with eerie calm, treating catastrophe as an experiment in cosmic entropy.

Patrick Stewart also makes a memorable, if brief, appearance as Dr. Armstrong, the head of a psychiatric hospital linked to the Space Girl’s psychic presence. His role builds to the film’s most grotesque and bizarre sequence: an exchange of minds, sudden possession, and an unnervingly intimate kiss with Railsback. The moment condenses everything Lifeforce represents—erotic, macabre, and unconcerned with boundaries. Stewart brings a gravitas that makes the absurd strangely compelling, a counterweight to Railsback’s volatility and Mathilda May’s silent allure.

May, as the unnamed Space Girl, says little but dominates the film through presence alone. She embodies an alien ideal of beauty and destruction, gliding through scenes with a composure that’s both sensual and predatory. Her nudity, much debated at the time, plays less as exploitation and more as elemental symbolism—the human body as an expression of both creation and death, desire and annihilation.

Supporting figures from the British military and government round out the ensemble, emphasizing the film’s descent into bureaucratic chaos. Michael Gothard’s Kane, a Ministry of Defence officer struggling to reconcile logic with the inexplicable, captures the helplessness of institutional order collapsing under cosmic threat. His pragmatic exchanges with Firth highlight competing instincts between reason and survival.

As the infection spreads, Lifeforce expands into a vision of urban apocalypse that fuses British science fiction and American spectacle. London becomes a nightmare tableau—crowds of shriveled corpses feed on energy while arcs of blue plasma swirl through the sky. The city’s fall evokes both George A. Romero’s zombie apocalypse and the metaphysical unease of Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass stories. Amid the insanity, Finlay and Firth remain the emotional touchstones, keeping the audience oriented as narrative logic begins to dissolve.

For all its ambition, however, Lifeforce suffers from erratic pacing and tonal whiplash. The first act unfolds with deliberate, moody wonder, then abruptly veers into frenzied exposition and psychic melodrama once the story reaches Earth. The balance between unsettling mystery and outright spectacle often collapses under its own weight. Scenes that should evoke cosmic terror sometimes tip into unintended camp, particularly in the dialogue-heavy middle stretch. Hooper’s direction, though visually imaginative, occasionally struggles to maintain coherence amid the script’s shifting identities—part creature feature, part disaster epic, part metaphysical drama. The editing, especially in the theatrical cut, undercuts tension with rushed transitions that leave emotional beats hanging. Railsback’s manic performance, while strangely compelling, can also verge on excess, blurring the line between conviction and chaos.

Tonally, the film wavers between awe and amusement. For some viewers, its earnest delivery will read as self-parody; for others, its collision of erotic horror and science fiction grandeur gives it a singular vitality. Lifeforce’s flaws are inseparable from its daring. It dares to fail boldly, and in that failure finds a kind of messy transcendence—larger than reason, too strange to fade.

In the end, Lifeforce lingers as one of the strangest hybrids of its era: part gothic fable, part erotic horror, part apocalyptic science fiction. It was too eccentric to find mainstream success, yet its sincerity and scope give it lasting resonance. The ensemble performances and tonal daring hold the film together, transforming potential chaos into something mythic—a story about possession, contagion, and humanity’s fatal pull toward the unknown.

Beneath its spectacle, the film engages in a deeper dialogue between gothic and cosmic horror traditions. Its characters represent a spectrum of responses to the incomprehensible: Fallada’s intellectual curiosity, Firth’s stoic resolve, Railsback’s frenzy, and May’s serene seduction. Together they form a portrait of human fragility in confrontation with the infinite. Where gothic horror finds fear in the collapse of reason, cosmic horror finds it in the vast indifference of the universe.

By fusing these lineages, Lifeforce becomes a mythic apocalypse that feels both intimate and vast—an encounter between flesh and void, terror and temptation. Its fusion of genres, ideas, and performances ensures its peculiar power endures, a reminder that some of the strangest failures of 1980s cinema are also its most visionary.