Though the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences claim that the Oscars honor the best of the year, we all know that there are always worthy films and performances that end up getting overlooked. Sometimes, it’s because the competition too fierce. Sometimes, it’s because the film itself was too controversial. Often, it’s just a case of a film’s quality not being fully recognized until years after its initial released. This series of reviews takes a look at the films and performances that should have been nominated but were, for whatever reason, overlooked. These are the Unnominated.

“Honorable men go with honorable men.” — Giovanni Cappa

1973’s Mean Streets is a story about Little Italy. The neighborhood may only be a small part of the sprawling metropolis of New York but, as portrayed in this film, it’s a unique society of its very own, with its own laws and traditions. It’s a place where the old ways uneasily mix with the new world. The neighborhood is governed by old-fashioned mafiosos like Giovanni Cappa (Cesare Danova), who provide “protection” in return for payment. The streets are full of men who are all looking to prove themselves, often in the most pointlessly violent way possible. When a drunk (David Carradine) is shot in the back by a teenage assassin (Robert Carradine), no one bothers to call the police or even questions why the shooting happened. Instead, they discuss how impressed they were with the drunk’s refusal to quickly go down. When a soldier (Harry Northup) is given a party to welcome him home from Vietnam, no one is particularly shocked when the solider turns violent. Violence is a part of everyday life.

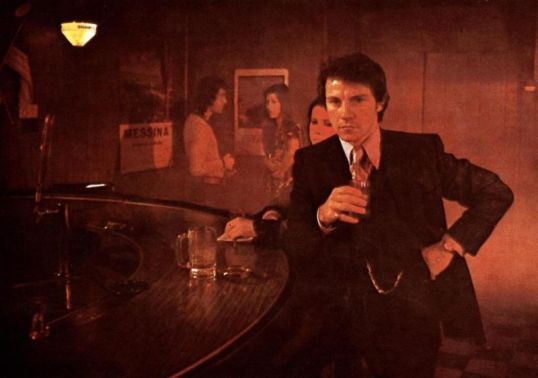

Charlie Cappa (Harvey Keitel) is Giovanni’s nephew, a 27 year-old man who still lives at home with his mother and who still feels guilty for having “impure” thoughts. Charlie prays in church and then goes to work as a collector for Giovanni. Giovanni is grooming Charlie to take over a restaurant, not because Charlie is particularly talented at business but just because Charlie is family. Giovanni warns Charlie not to get involved with Teresa (Amy Robinson) because Teresa has epilepsy and is viewed as being cursed. And Giovanni particularly warns Charlie not to hang out with Teresa’s cousin, Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro). Johnny Boy may be charismatic but everyone in the neighborhood knows that he’s out-of-control. His idea of a good time is to blow up mailboxes and shoot out street lamps. Charlie, who is so obsessed with sin and absolution that he regularly holds his hand over an open flame to experience the Hellfire that awaits the unrepentant sinner, finds himself falling in love with Teresa (though it’s debatable whether Charlie truly understands what love is) and trying to save Johnny Boy.

Charlie has other friends as well. Tony (David Proval) runs the bar where everyone likes to hang out and he seems to be the most stable of the characters in Mean Streets. He’s at peace with both the neighborhood and his place in it. Meanwhile, Michael (Robert Romanus) is a loan shark who no one seems to have much respect for, though they’re still willing to spend the afternoon watching a Kung Fu movie with him. Michael knows that his career is dependent on intimidation. He can’t let anyone get away with not paying back their money, even if they are a friend. Johnny Boy owes Michael a lot of money and he hasn’t paid back a single dollar. Johnny Boy always has an excuse for why he can’t pay back Michael but it’s obvious that he just doesn’t want to. Charlie realizes that it’s not safe for Johnny Boy in Little Italy but where else can he go? Brooklyn?

Mean Streets follows Charlie and his friends as they go about their daily lives, laughing, arguing, and often fighting. All of the characters in Mean Streets enjoy a good brawl, despite the fact that none of them are as tough as their heroes. A chaotic fight in a pool hall starts after someone takes offense to the word “mook,” despite the fact that no one can precisely define what a mook is. The fights goes on for several minutes before the police show up to end it and accept a bribe. After the cops leave, the fight starts up again. What’s interesting is that the people fighting don’t really seem to be that angry with each other. Fighting is simply a part of everyday life. Everyone is aggressive. To not fight is to be seen as being weak and no one is willing to risk that.

Mean Streets was Martin Scorsese’s third film (fourth, if you count the scenes he shot before being fired from The Honeymoon Killers) but it’s the first of his movies to feel like a real Scorsese film. Scorsese’s first film, Who’s That Knocking On My Door?, has its moments and feels like a dry run for Mean Streets but it’s still obviously an expanded student film. Boxcar Bertha was a film that Scorsese made for Roger Corman and it’s a film that could have just as easily been directed by Jonathan Demme or any of the other young directors who got their start with Corman. But Mean Streets is clearly a Scorsese film, both thematically and cinematically. Scorsese’s camera moves from scene to scene with an urgent confidence and the scene where Charlie first enters Tony’s bar immediately brings to mind the classic tracking shots from Goodfellas, Taxi Driver, and Casino. One gets the feeling that Pete The Killer is lurking somewhere in the background. The scenes between Keitel and De Niro are riveting. Charlie attempts to keep his friend from further antagonizing Michael while Johnny Boy tells stories that are so long and complicated that he himself can’t keep up with all the details. Charlie hold everything back while Johnny Boy always seems to be on the verge of exploding. De Niro’s performance as Johnny Boy is one that has been duplicated but never quite matched by countless actors since then. He’s the original self-destructive fool, funny, charismatic, and ultimately terrifying with his self-destructive energy.

Mean Streets was Scorsese’s first box office success and it was also the film that first brought him widespread critical acclaim. However, in a year when the totally forgotten A Touch of Class was nominated for Best Picture, Mean Streets did not receive a single Oscar nomination, not even for De Niro’s performance. Fortunately, by the time Mean Streets was released, De Niro had already started work on another film about the Mafia and Little Italy, The Godfather Part II.

Previous entries in The Unnominated:

Three Detroit auto workers (played by Harvey Keitel, Yaphet Kotto, and Richard Pryor) are fed up.

Three Detroit auto workers (played by Harvey Keitel, Yaphet Kotto, and Richard Pryor) are fed up.