“I have no other choice.” — Yoo Man-su

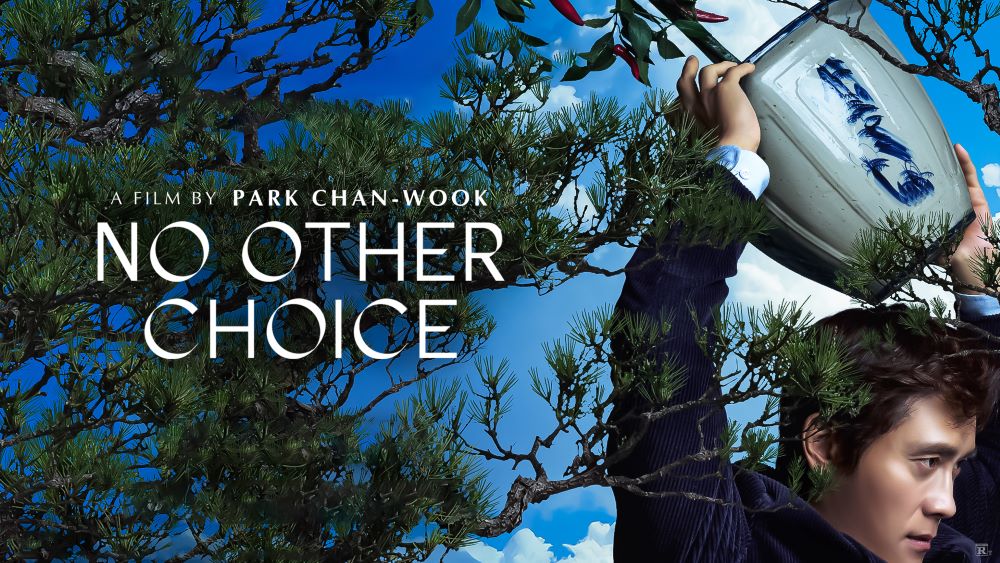

No Other Choice grabs you right away with its wild premise—a loyal company man gets canned and decides to literally eliminate his job competition to claw his way back up. It’s one of the standout international films from last year, popping up on countless top films of 2025 lists for its gutsy mix of workplace rage and murderous absurdity. Park Chan-wook delivers a dark, twisty ride blending sharp satire with outright farce, and while it doesn’t always stick the landing perfectly, that bold energy and uncomfortable laughs make it a must-watch.

The story kicks off in a picture-perfect suburban home where Man-su, a longtime paper factory manager played by Lee Byung-hun, basks in the comforts of a solid middle-class life. He’s got the big house, loving wife Mi-ri, two kids, and even those flashy dogs that scream success. Everything feels polished and stable, almost too good to be true, which is exactly the point. Then the axe falls—layoffs hit, and suddenly Man-su’s years of service mean nothing in a brutal job market stacked against him. Every opening has a ranked list of candidates, and he’s always near the bottom. Desperation sets in, and he hatches a grim plan: take out the guys ahead of him one by one.

What makes this setup pop is how Park turns a simple “what if” into a mirror for real-world frustrations. Man-su’s logic spirals from understandable rage to unhinged obsession, repeating his mantra of having “no other choice” like it’s gospel. Each target he stalks feels like a warped reflection of himself—aging has-beens clinging to relevance or eager young hotshots with families of their own. It’s not just about the kills; it’s the quiet horror of seeing your own fears staring back. The film nails that sinking feeling of obsolescence, where loyalty gets you nowhere and the system chews people up without a second thought.

The action sequences are where Park’s signature style shines brightest. That first murder attempt is a masterclass in chaos—a shaky standoff with an antique pistol turns into a frantic, slapstick melee in some oversized wooden house. Blood flies, furniture shatters, and it’s all choreographed with such precision it borders on balletic. He mixes genuine tension with cartoonish escalation, making you laugh even as things get gruesome. It’s the kind of over-the-top violence that recalls his classics like Oldboy, but lighter, almost playful in its excess. You never know if the next swing will end it or devolve into more absurdity, and that unpredictability keeps the pulse racing.

At home, though, the real damage unfolds. Mi-ri, brought to life by Son Ye-jin in a quietly devastating turn, starts as the supportive spouse but cracks under the strain. They cut back on luxuries like tennis lessons and fancy music classes, but it’s the growing paranoia that poisons everything. Snide arguments erupt, kids get tangled in cover stories for the police, and the once-idyllic house feels like a pressure cooker. Park smartly shifts focus here, showing how one man’s breakdown ripples out to fracture his family. Mi-ri’s mix of worry, resentment, and tough love grounds the madness, reminding us this isn’t just a lone wolf tale—it’s about collateral damage in the pursuit of “normalcy.”

As a jab at corporate culture, the movie lands some solid punches. Those sterile job interviews and endless applicant lists capture the dehumanizing grind perfectly, where workers are just numbers on a spreadsheet. Man-su’s humiliation builds layer by layer, from polite rejections to outright indifference, culminating in a factory scene that’s equal parts poetic and punishing. He ends up as the last human holdout amid a sea of machines, a stark symbol of misplaced faith in the grind. Park doesn’t pretend to offer solutions, but he forces you to confront how capitalism turns colleagues into rivals and dignity into a luxury good.

That said, the film isn’t content to just indict the system—it digs into Man-su’s flaws too. He’s no innocent victim; he’s vain, stubborn, and blinded by pride. Moments of potential redemption pop up—a heartfelt chat with a fellow job-seeker, a glimpse of empathy for a rival dad—but he barrels past them every time. This refusal to pivot makes him compellingly human, a portrait of wounded ego that stops short of full villainy. Lee Byung-hun sells it all with subtle shifts: the forced smile in interviews, the twitchy hands during stakeouts, the hollow justifications whispered to himself. He’s magnetic, drawing sympathy even as you root for his comeuppance.

Visually, Park pulls out all the stops. Bold camera moves, clever framing, and those vintage thriller tricks—fancy dissolves, sharp cuts—give it a retro flair amid modern polish. Conversations crackle with visual wit, turning mundane chats into tense standoffs. The color palette swings from warm domestic glows to cold, shadowy nights, mirroring Man-su’s slide. It’s indulgent stuff, the kind of filmmaking that demands a big screen, though it occasionally tips into showiness when the plot needs room to breathe.

The supporting cast fleshes out the world nicely. Victims aren’t faceless; each gets a quick, vivid sketch that humanizes the body count. Detectives poke around with dry humor, adding a procedural edge without stealing focus. Son Ye-jin steals scenes effortlessly, her Mi-ri evolving from enabler to antagonist in the subtlest ways— a raised eyebrow here, a weary sigh there. It’s ensemble work that elevates the whole, making the satire feel lived-in rather than preachy.

Where it stumbles is in the pacing and bloat. The cat-and-mouse games repeat a bit too faithfully—stalk, scheme, screw-up, repeat—and by the third or fourth loop, the formula shows. Subplots with cops and side characters tangle up the momentum, diluting the core spiral. Park juggles a lot: farce, thriller beats, family drama, economic allegory. It mostly coheres, but you sense he’s wrestling to tie it all together. The ending, while punchy, leans hard on irony, which might leave some wanting deeper catharsis or ambiguity.

Still, flaws and all, No Other Choice pulses with invention and earned its spot as one of 2025’s best international gems, racking up mentions across year-end top lists from critics worldwide. It’s a timely gut-punch for anyone who’s felt the job market’s cruelty, wrapped in enough dark humor and style to linger. Not Park’s tightest, but his wildest in years—a messy, mean-spirited blast that dares you to laugh at the abyss. If you’re up for a thriller that treats resumes like kill lists and HR as the true horror, dive in. Just don’t expect tidy morals or easy outs; this one’s as complicated as real desperation gets.