As Brad mentioned earlier, today is Bruce Dern’s birthday!

Bruce Dern is a favorite actor of mine. He’s one of those performers who, over the course of his very long career, has appeared in all sorts of different and occasionally odd films, sometimes as a lead but most often as a character actor. He appeared in biker films, westerns, literary adaptations, and Oscar-winners. He killed John Wayne in The Cowboys. He introduced Peter Fonda to acid in The Trip. (Dern, for his part, has said that he the only person on the set of that film who has never done acid.) He captured the trauma of Vietnam in Coming Home. He played one of the great hyperactive cops in The Driver. He came close to playing Tom Hagen in The Godfather and was the original choice for the attorney who was eventually played by Jack Nicholson in Easy Rider.

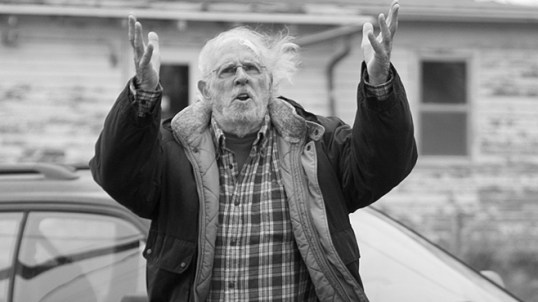

In 2013’s Nebraska, he broke my heart.

In Nebraska, Dern plays Woody Grant, an elderly man who is convinced that he’s won a million-dollar sweepstakes. Everyone around him, including his wife (June Squibb) and his oldest son (Bob Odenkirk), realizes that the sweepstakes is a scam and that Woody has actually won nothing. But Woody is convinced that a million dollars is waiting for him. All he has to do is somehow make it from Montana to Nebraska. At first, Woody attempts to walk along the interstate. When that doesn’t work and the police end up arresting him and sending him home, his youngest son, David (Will Forte), agrees to drive Woody down to Lincoln, Nebraska. David knows that there’s not any money waiting for Woody but, unlike his mother and his older brother, David hasn’t given up on the idea of connecting with his father.

Nebraska is a road movie, with the majority of the film following David and Woody as the drive through rural and smalltown America. They stop off in Woody’s former hometown, where they meet Woody’s brother (Rance Howard) and also Woody’s former business partner, a bully named Ed (Stacy Keach). Ed is convinced that Woody stole money from him. Woody blames Ed for the loss of his air compressor. Their anger has simmered for years and, at first, it’s tempting to assume that it’s simply one of those grudge matches that old men seem to have a weakness for. But Ed turns out to truly be a rotten human being and Woody …. well, Woody his own problems but at least he’s not as bad as Ed.

Before I say anything else, I want to praise the entire cast. June Squibb, Bob Odernkirk, Stacy Keach, Rance Howard, Melinda Simonsen (who has a small role as a receptionist in Lincoln), they all bring their characters to memorable life. Will Forte is the heart of the film, trying to keep his family together and standing up for his father when it matters. If you only know Will Forte as MacGruber, you need to see Nebraska. That said, this film is dominated by Bruce Dern’s poignant, sad, and often very funny performance as Woody Grant. Woody is a flawed character and Dern wisely doesn’t try to sentimentalize or downplay any of those flaws. He drinks too much, he neglected his family when he was younger, he holds a grudge, and he’s incredibly stubborn. But, as played by Dern, you just can’t help but like Woody and hope that he finds some sort of happiness. Even though the viewer, like everyone else in Woody’s life, knows that the sweepstakes is a scam, it’s still hard not to spend the film hoping that Woody will prove everyone wrong when he makes it to Nebraska.

Nebraska was nominated for Best Picture while both Bruce Dern and June Squibb picked up acting nominations. That year, the Best Picture race was dominated by 12 Years A Slave. Matthew McConaughey won Best Actor for Dallas Buyers Club while Lupita Nyong’o won Best Supporting Actress for 12 Years A Slave. Alexander Payne lost Best Director to Gravity’s Alfonso Cuaron. Gravity also won the Oscar for Best Cinematography, defeating Nebraska’s gorgeous black-and-white imagery.

Oscars or not, Nebraska is a wonderful, late career showcase for the great Bruce Dern.