Taking place in a vaguely futuristic world, the 1974 Australian film, The Cars That Ate Paris, opens with an attractive and impossibly happy couple going for a drive in the countryside and getting killed in a truly horrific car accident, one that apparently was deliberately set up.

Meanwhile, two brothers — Arthur (Terry Camilleri) and George (Rick Scully) — are traveling across Australia, in search of work. Everywhere they go, they see long lines of desperate people looking for a way to make money, suggesting that the economy has basically collapsed. George does the driving, largely because Arthur’s license was taken away after he accidentally killed a pedestrian. Arthur is struggling with both the guilt and a phobia of cars in general.

That phobia only gets worse after Arthur and George are involved in a automotive accident of their own. George is killed but Arthur survives. Taken to the small, rural town of Paris, Arthur is adopted as a bit of a mascot by the town’s seemingly friendly mayor, Len Kelly (John Mellion). At first, Arthur is relieved to have survived but he soon comes to realize that the residents of Paris have no intention of ever letting him leave.

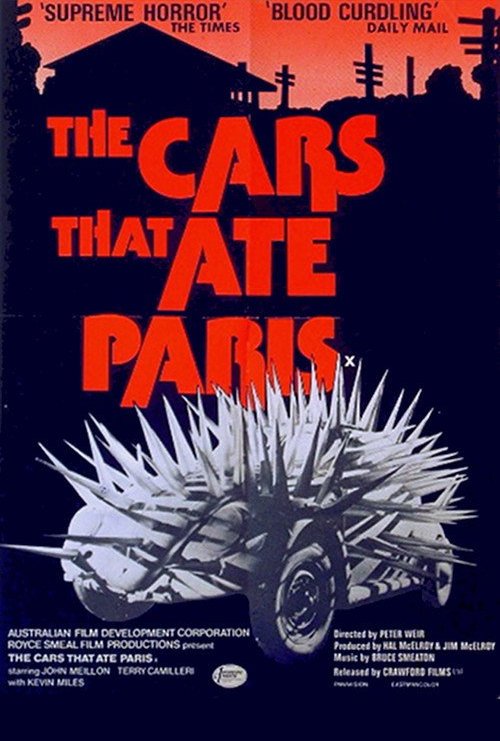

Paris, it turns out, is a bit of a strange place. The entire economy is based on collecting scrap metal from the many cars that crash within the city limits. The local hospital is full of car crash victims, the majority of whom end up getting lobotomized and used as test subjects for the local doctor. Indeed, the only thing that kept Arthur from a similar fate was that the mayor assured everyone that Arthur’s phobia of driving has rendered him “harmless.” (And just to make sure that Arthur doesn’t lose that phobia, he’s sent to a psychologist who spends nearly the entire session showing him grotesque pictures of car accident victims.) Though the mayor continually talks about how Paris represents the “pioneer spirit” that made Australia great, the town’s teenagers don’t seem to be too impressed with the place. They spend all of their time driving around in cars that they’ve modified into small tanks. (Their leader drives a compact car that has been covered in metal spikes, transforming it into a motorized porcupine.) Arthur wants to escape the town but can he conquer not only his own fears but also avoid being killed by the citizens who have adopted him?

The Cars That Ate Paris is a rather uneven film. It gets off to a good start and the town is memorably creepy but, once Arthur had been adopted by the mayor, it starts to drag and not much happens until the teens finally get around to turning on their elders during the final fifteen minutes of the film. Arthur is a frustratingly passive character and his car phobia never really feels credible. The film attempts to mix horror, science fiction, and satire but it comes across as being rather disjointed. Thematically, it’s probably most interesting as a precursor to the Mad Max films, having been inspired by the same Australian car culture that inspired George Miller. In fact, The Cars That Ate Paris almost feels like a prequel to the Mad Max films. One half expects a young Mel Gibson to pop up at the end, wearing Max’s patrolman uniform and shaking his head at the madness of it all.

That said, the film features a few striking images and Paris is a memorably desolate town. This really isn’t that surprising, given that The Cars That Ate Paris was directed by Peter Weir. This was Weir’s first feature film, though he had previously directed several shorts, and the film very much comes across as being the work of a talented artist who was still learning how to use those talents to tell a compelling story. In the end, Peter Weir’s involvement is the main reason to watch The Cars That Ate Paris. The film doesn’t really work but it does provide a chance to see an early effort from someone who would eventually become one of the most interesting directors of his time.