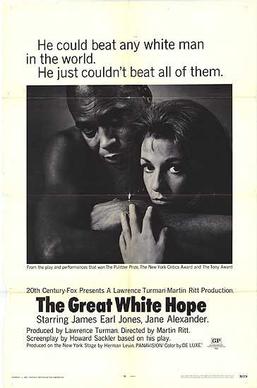

The year is 1910 and the sports world is in a panic. For the first time, a black man has won the title of the heavyweight champion of the world. Jack Jefferson (James Earl Jones) had to go to Australia because no American city would agree to host the fight but he came out of it victorious. The proud and outspoken Jefferson finds himself targeted by both the white establishment and black activists who claim that Jefferson has not done enough for his community.

The year is 1910 and the sports world is in a panic. For the first time, a black man has won the title of the heavyweight champion of the world. Jack Jefferson (James Earl Jones) had to go to Australia because no American city would agree to host the fight but he came out of it victorious. The proud and outspoken Jefferson finds himself targeted by both the white establishment and black activists who claim that Jefferson has not done enough for his community.

It’s not just Jefferson’s success as a boxer that people find scandalous. It’s also that the married Jefferson has a white mistress, a socialite named Eleanor Brachman (Jane Alexander, in her film debut). While boxing promoters search for a “great white hope” who can take the title from Jefferson, the legal authorities attempt to arrest Jefferson for violating the Mann Act by supposedly taking Eleanor across state lines for “immoral purposes.” Jefferson and Eleanor end up fleeing abroad but even then, their relationship is as doomed as Jefferson’s reign as the heavyweight champ.

Based on a Pulitzer-winning stage play by Howard Sackler, The Great White Hope features Jones and Alexander recreating the roles for which they both won Tonys. Both Jones and Alexander would go on to receive Oscar nominations for their work in the film version. It was the first nomination for Alexander and, amazingly, it was the only nomination that Jones would receive over the course of his career. (It surprises me that he wasn’t even nominated for his work in Field Of Dreams.) Both Jones and Alexander give powerful performances, with Jones dominating every scene as the proud, defiant, and often very funny Jack Jefferson. Jones may not have had a boxer’s physique but he captured the attitude of a man who knew he was the best and who mistakenly believed that would be enough to overcome a racist culture. (Speaking of racist, legendary recluse Howard Hughes reportedly caught the film on television and was so offended by the sight of Jones kissing Alexander that he thought about buying NBC to make sure that the movie would never be aired again.) Hal Holbrook, Chester Morris, Moses Gunn, Marcel Dalio, and R.G. Armstrong all do good work in small roles.

Unfortunately, The Great White Hope still feels like a filmed stage play, despite the attempts made to open up the action. Martin Ritt was a good director of actors but the boxing scenes are never feel authentic and the middle section of the film drags. Jones and Alexander keep the film watchable but The Great White Hope is never packs as strong of a punch as its main character.