It’s been a strange Oscar season and it could get even stranger. Several critics and industry insiders are speculating that, on February 24th, Argo might win the Oscar for best picture without winning in any other category. As strange as that may sound, Argo would not be alone in achieving this distinction. In the past, 3 films have won best picture without winning anything else.

Mutiny on the Bounty, the best picture of 1935, is one of those films.

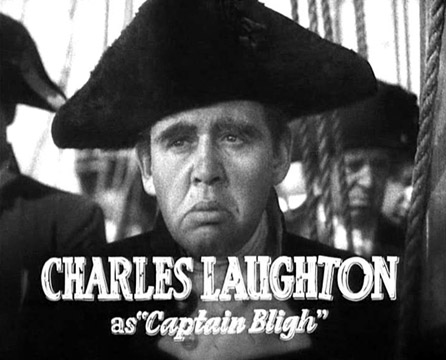

Based (rather loosely, according to many historians) on a true story, Mutiny on the Bounty tells the story of one of the most controversial events in maritime history. The HMS Bounty leaves England in 1787 on a two-year voyage to Tahiti. The Bounty is manned by a disgruntled crew (many of whom have been forced into Naval service) and is captained by a tyrant named William Bligh (Charles Laughton). Bligh has little use for the majority of his crew and thinks nothing of having a man whipped until he is dead for even the pettiest of infractions.

Blight’s lieutenant is Fletcher Christian (Clark Gable), a compassionate man who disapproves of Bligh’s methods. As the voyage continues, Christian grows more and more vocal with his disgust towards Bligh. When the ship finally reaches Tahiti, Christian falls in love with a local Tahitian girl and defies Bligh’s direct orders so that he can spend time with her.

It’s only after the ship leaves Tahiti and Bligh’s tyranny leads to the death of an alcoholic crew member that Christian finally leads the mutiny of the film’s title. The rest of the film is divided between Bligh’s surprisingly heroic efforts to survive after being set adrift in a lifeboat and Christian’s attempts to avoid being captured by British authorities. Caught up in the middle of all of this is Christian’s friend (and audience surrogate), Roger Byam (Franchot Tone).

Mutiny on the Bounty was one of the biggest box office hits of 1935 and it received 8 Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, and a record-setting 3 nods for Best Actor with Clark Gable, Charles Laughton, and Franchot Tone all receiving nominations. However, out of those 8 nominations, Mutiny only won the award for Best Picture while John Ford’s The Informer took home the Oscars for Best Director and Actor. Mutiny on the Bounty was the third (and, as of this writing, the last) best picture winner to fail to win any other categories.

For a film that lost dramatically more awards than it won, Mutiny on the Bounty still holds up pretty well. Director Frank Lloyd keeps the film moving at a quick pace and perfectly captures not only the misery of the Bounty but the joyful paradise of Tahiti as well. Lloyd is at his best during the short sequence of scenes that depict Bligh’s efforts to reach safety after being forced off of the Bounty. During this sequence, the audience is forced to reconsider both Captain Bligh and everything that we’ve seen before. It introduces an intriguing hint of ambiguity that is not often associated with films released in either the 1930s or today.

Of the three nominated actors, Clark Gable and Charles Laughton both give performances that remain impressive today. In the role of Fletcher Christian, Gable is the literal personification of masculinity and virility. Meanwhile, in the role of Bligh, Laughton is hardly subtle but he is perfectly cast. If Gable’s performance is epitomized by his charming smile than Laughton’s is epitomized by his constant glower. Wisely, neither the film nor Laughton ever make Bligh out to be an incompetent captain. As is shown after the mutiny, the film’s Bligh truly is as capable a navigator and leader as everyone initially believes him to be. Unlike many cinematic tyrants, Blight’s tyranny is not the result of insecurity. Instead, Bligh is simply a tyrant because he can be. Laughton and Gable are both so charismatic and memorable that Franchot Tone suffers by comparison. However, even Tone’s bland performance works to the film’s advantage. By being so normal and boring, Roger Byam is established as truly being the sensible middle between Gable’s revolutionary and Laughton’s tyrant.

Mutiny on the Bounty remains an exciting adventure film and it certainly holds up better than some of the other films that were named best picture during the Academy’s early years. If Argo only wins one Academy Award next Sunday, it’ll be in good company.