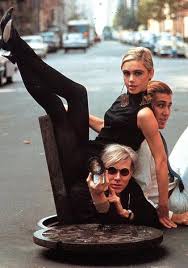

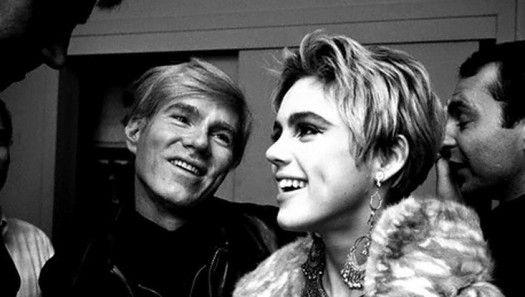

In March of 1965, Andy Warhol, Gerard Malanga, and Chuck Wein went to the New York City apartment of Edie Sedgwick and made a movie. Edie Sedgwick, at that time, was a 22 year-old model who had been christened a “youthquaker” by Vogue. She was also, for a year or so, the best-known member of Andy Warhol’s ensemble. Of all the so-called superstars that spent time with Warhol and appeared in his films, Edie was the one who actually was a star.

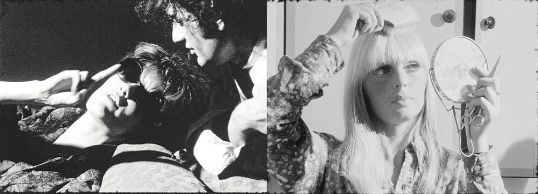

The film opens with Edie waking up, walking around her bedroom, smoking a cigarette, popping pills, exercising, and lounging in bed. (That’s pretty much my morning routine too, except for the cigarettes.) She doesn’t speak. The only sound that we hear is a record being played in the background and the whirring of Warhol’s camera. Because of a faulty lens, the first 30 minutes of Poor Little Rich Girl are out-of-focus. We can see Sedgwick’s form as she moves and we can, for the most part, tell what she’s doing but we can’t see any exact details. Her face is a blur and sometimes, her body seems to disappear into the walls of the room itself. It’s a genuinely disconcerting effect, even if it was an accident on Warhol’s part. Edie is there but she’s not there. The blurry image seems to reflect an unfocused life. Edie is the poor little rich girl of the title and indeed, she was known as a socialite before she even became a part of Warhol’s circle. The blurriness indicates that she has everything but it can’t be seen.

After 30 minutes, the film comes into focus. Clad in black underwear, Edie answers questions from Chuck Wein, who remains off-camera. Sometimes, we can hear Chuck’s questions and sometimes, we can’t. Our focus is on Edie’s often amused reaction to the questions, even more so than her actual answers. Edie smokes a pipe and looks at herself in her mirror and she talks about how she blew her entire inheritance in just a manner of days. She raids her closet and tries on clothes while Wein offers up his opinions. Edie is living the ultimate fantasy of trying on different outfits while your gay best friend makes you laugh with his snarky comments. Edie comes across as someone who is living in the present and not worrying about what’s going to happen in the future. It’s only when she nervously smiles that we get hints of the inner turmoil that came to define her final years. The camera loves Edie and, even appearing in what is basically a home movie, Edie has the screen presence of a star. There was nothing false about Edie Sedgwick.

Watching the film today, of course, it’s hard not to feel a bit sad at the sight of a happy Edie Sedgwick. While Edie would become an underground star as a result of her association with Andy Warhol and his films, their friendship ended when Edie tried to establish a career outside of Warhol’s films. Edie’s own struggle with drugs and her mental health sabotaged her career and she died at the age of 28. I first read George Plimpton’s biography of Edie Sedgwick when I was sixteen and I immediately felt a strong connection to her and her tragic story, so much so that I was actually relieved when I made it to my 29th birthday. Though most people ultimately see Edie Sedgwick as being a tragic figure, I prefer to remember Edie as she appeared in the second half of Poor Little Rich Girl, happy and in focus.