This is the story of two rival snooker players and their grudge match.

This is the story of two rival snooker players and their grudge match.

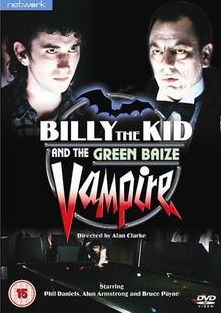

Billy The Kid (Phil Daniels) is an up-and-coming snooker player. Cocky and cockney, Billy is arrogant but he is also beloved by the working class. His manager, The One (Bruce Payne), has fallen into debt to a loan shark known as The Wednesday Man (Don Henderson). The Wednesday Man agrees to release The One if he can convince Billy The Kid to play a 17-frame snooker match against Maxwell Randall (Alun Armstrong).

Maxwell Randall is the reigning world champion snooker player. Supported by the upper class, Randall has been playing snooker for centuries. He’s known as the Green Baize Vampire, both because of his resemblance to Bela Lugosi and also because he actually is a vampire, complete with fangs, a casket that doubles as a snooker table, and a London mansion that looks like a castle.

With the help of an unscrupulous tabloid reporter (Louise Gold), The One generates a generational and class rivalry between Billy The Kid and the Green Baize Vampire. The two agree to meet in a snooker match, with the requirement that the loser of the match never play another game of snooker.

Billy The Kid and the Green Baize Vampire is many things. It’s a satire of sports films and the British class system and it is certainly no coincidence that the upper class is represented by a vampire. It’s also a musical, with the cast performing Brechtian songs about how snooker is life. Unintentionally, it’s a tribute to the ability of the British to get caught up in some of the most boring sports even invented. At first, it seems like the last thing that you would expect to be directed by Alan Clarke, though the film does feature his usual political subtext and a few of his trademark tracking shots.

The film is memorably strange and it features strong performances from Phil Daniels, Alun Armstrong, and Bruce Payne but, at times, it can be a chore to sit through. If you’re not already a fan of snooker, this film won’t change your mind. (However, if you are a fan of snooker, you’ll probably enjoy the match between Billy and Maxwell.) For me, the main problem was the songs, none of which are really good enough to justify their inclusion in a film that already felt too self-indulgent even without being a musical. I can understand why this film has a cult following but it didn’t really work for me.