David Lynch never won a competitive Oscar.

He received an honorary award from the Academy in 2019. He generated some minor but hopeful buzz as a possible nominee for Best Supporting Actor for his role in Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans. He was nominated for Best Director three times and once for Best Adapted Screenplay. But he never won an Oscar and indeed, even his nominations felt like they were given almost begrudgingly on the part of the Academy. In an industry that celebrated conformity and put the box office before all other concerns, David Lynch was an iconoclastic contrarian and the Academy often didn’t do know what to make of him. Of the many worthy films that he directed, only one David Lynch film was nominated for Best Picture and, in my opinion, it should have won.

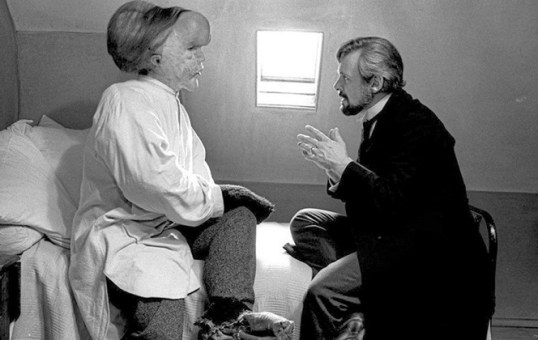

1980’s The Elephant Man is based on the true story of Joseph Merrick (renamed John for the film), a man who was horribly deformed and terribly abused until he was saved from a freak show by a surgeon named Dr. Frederick Treves. The sensitive and intelligent Merrick went on to become a celebrity in Victorian London, visited by members of high society and allowed to live at London Hospital. (Even members of the royal family dropped in to visit the man who had once been forced to live in a cage.) Merrick lived to be 27 years old, ultimately dying of asphyxiation when he attempted to lie down and, in Treves’s opinion, sleep like a “normal person” despite his oversized and heavy head. In the film, Merrick is played by John Hurt (who gives a wonderful performance that, despite Hurt acting under a ton on makeup, still perfectly communicates Merrick’s humanity) while Treves is played by Anthony Hopkins, who is equally as good as Hurt. (Hurt was nominated for Best Actor but Hopkins was not. Personally, I prefer Hopkins’s performance as the genuinely kind Dr. Treves to any of his more-rewarded work as Dr. Lecter.) The rest of the cast is made up of veteran British stars, including John Gielgud, Wendy Hiller, Freddie Jones, and Kenny Baker.

Lynch’s version of The Elephant Man is only loosely based on the facts of Merrick’s life. It opens with a disturbing fantasy sequence (one which I assume is meant to be from Merrick’s point of view) in which a herd of elephants strike down Merrick’s mother and then appear to assault her. Shot in stark black-and-white and often featuring the sounds of droning machinery in the background (in many ways, The Elephant Man feels like it takes place in the same world as Eraserhead), the first half of The Elephant Man feels like a particularly surreal Hammer film. (Veteran Hammer director Freddie Francis served as The Elephant Man‘s cinematographer.) Merrick is kept off-camera and, when we finally do see his face, it’s in a split-second scene in which Merrick is as terrified as the person who sees him. Before we really meet Merrick, we’ve already heard Treves and the hospital administrator (John Gielgud) discuss all of the clinical details of his condition. We know why he’s deformed. After we see him, we know how he’s deformed. After all of that, the audience is finally ready to know Merrick the human being. Without engaging in too much obvious sentimentality, Lynch shows us that Merrick is a kind soul, one who has been tragically mistreated by the world. Just as with the real Merrick, almost everyone who meets the film’s John Merrick is ultimately charmed by him. In the film, Merrick is kidnapped by his former owner, the alcoholic Bytes (Freddie Jones), who wants again puts Merrick on display in a cage. In the end, it’s Merrick’s fellow so-called “freaks” who set him free and allow him to return to the hospital, where he has one final vision of his mother. This vision is a much less disturbing than the one that opened the film. The film celebrates the humanity of John Merrick but is also reveals the genius of David Lynch. There’s so many moments when the film could have gone off the rails or become too obvious for its own good. But Lynch’s unique style so draws you into the film’s world that even the mysterious visions of his mother somehow feel completely necessary and natural. The Elephant Man is the David Lynch film that makes me cry. Lynch was a surrealist with a heart.

The Elephant Man was only David Lynch’s second film. He was hired to direct by none other than Mel Brooks, who produced the film but went uncredited to prevent people from thinking it would be a comedy. (Lynch, however, did cast Brooks’s wife, Anne Bancroft, as an actress who visits Merrick.) Brooks hired Lynch after seeing Eraserhead and recognizing a talent that many in Hollywood would never have had the guts to take a chance on. (Despite the success of Eraserhead on the midnight circuit, David Lynch was working as a roofer when he was offered The Elephant Man and had nearly given up on the idea of ever making another film.) Reportedly, Brooks stayed out of Lynch’s way and protected him from other executives who fears Lynch’s version of the story would be too strange to be a success. Lynch and Brooks proved those doubters wrong. Acclaimed by critics and popular with audiences, The Elephant Man was nominated for Best Picture and David Lynch was nominated for Best Director. I like Ordinary People. I like Raging Bull. But The Elephant Man was the film that should have won in 1980.

The Elephant Man remains a powerful movie and an example of how an independent artist can make a mainstream movie without compromising his vision. (Of course, I imagine it helps to have a producer who has the intelligence and faith necessary to stay out of your way.) David Lynch may be gone but his art will live forever. The Elephant Man will continue to make me cry for the rest of my life and for that, I’m thankful.

This movie, the book, and John Merrick touched me deeply. I even named my ginger cat at the time Merrick. Wonderful, wonderful film.

LikeLike

Pingback: Lisa Marie’s Week In Review: 1/13/25 — 1/19/25 | Through the Shattered Lens