Hentai: slang for the Japanese term “hentai seiyoku” which literally means sexual perversion. A word used by Western fans of anime to signify anime/manga as being of the pornographic variety.

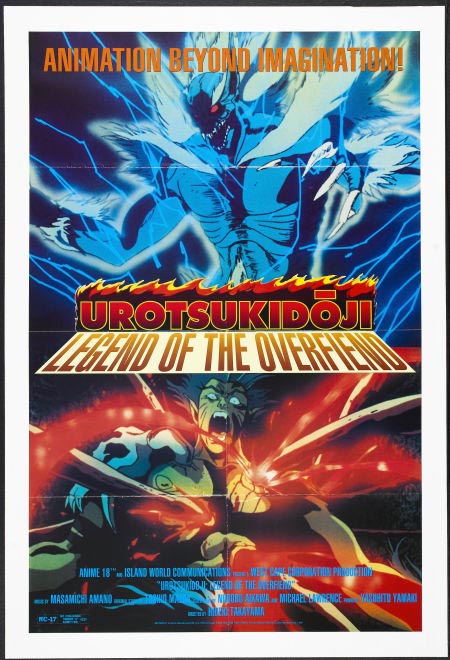

In 1990, during my junior year of high school, I was introduced to a form of animation unlike anything I had known before—the darkly imaginative and transgressive world of hentai. While explicit Japanese media had existed long before, the particular title that marked my first encounter with the genre was Chōjin Densetsu Urotsukidōji. The work did not simply define hentai; it transformed how adult animation would be viewed by audiences in both Japan and the West.

Prior to its release, erotic or explicit manga had long circulated quietly within Japan, often categorized separately from mainstream entertainment. Yet when mangaka Maeda Toshio’s Chōjin Densetsu Urotsukidōji was adapted into animation by director Takayama Hideki in the late 1980s, something shifted. The result was a film that combined the grotesque, the apocalyptic, and the erotic into a single overwhelming experience. Takayama’s adaptation was not content to merely illustrate Maeda’s ideas—it amplified them into a fever dream of violence and desire that pushed the medium into territory rarely explored in animation.

This era in Japanese media was also defined by strict obscenity laws. Direct depictions of genitalia or explicit intercourse were prohibited, both in live-action and animation. To circumvent these limitations, artists employed mosaics or invented visual metaphors. Takayama approached the problem with disturbing creativity: he replaced human anatomy with monstrous, tentacle-like appendages. These served a dual purpose—they satisfied censors while reinforcing the story’s occult and otherworldly atmosphere. Inadvertently, this gave rise to one of the most infamous tropes in hentai culture: “tentacle rape.” What began as a method of evading censorship evolved into a symbol of perversion, horror, and fascination.

Though Maeda initially regarded Takayama’s interpretation as excessively cruel and sadistic, he expressed admiration for the director’s ability to explore the darker undercurrents of his story. In time, Maeda’s own works would adopt similar motifs, blending eroticism with the supernatural. His later projects—including Yōjū Kyōshitsu Gakuen, Adobenchā Kiddo, and the enduring Injuu Gakuen La Blue Girl—refined the sensibilities born from Urotsukidōji, mixing violence, humor, and demonic imagery. These works often shifted in tone but never strayed far from the genre’s defining combination of horror and sexual excess.

Chōjin Densetsu Urotsukidōji can best be described as a collision of disparate influences: the mythic nihilism of H. P. Lovecraft, the explicit confrontational style of Larry Flynt, and the occult transgression of Aleister Crowley, all underscored by the philosophical cruelty associated with the Marquis de Sade. The film’s narrative combines apocalypse with pornography, constructing a universe where gods, demons, and humans become locked in violent and erotic cycles of destruction and rebirth. It is both a nightmare and a spectacle, a work that examines desire as an extension of cosmic chaos.

Watching the OVA as a seventeen-year-old was an experience of shock and bewilderment. Nothing in my understanding of animation prepared me for it. The optimism and adventure of series like Robotech, Starblazers, and Voltron stood in stark contrast to the nihilistic intensity of Urotsukidōji. If such a term had been common at the time, “culture shock” would have described it perfectly. Yet beyond my initial disorientation, I recognized something compelling beneath the shock value—a strange vision that treated eroticism not as mere indulgence but as a reflection of human fear and fascination.

Takayama’s film succeeded because it used obscenity as both spectacle and metaphor. The sexualized violence was horrifying, but it also emphasized the collapse of moral order within its world. The boundaries between sensuality and monstrosity blurred, suggesting that both sprang from the same primal source. In this way, Urotsukidōji transformed its limitations into aesthetic strength. Censorship forced invention, and invention created symbolism: the tentacle became an image of corruption, domination, and inhuman desire.

When Urotsukidōji began circulating in the West through VHS imports in the early 1990s, it acquired immediate notoriety. For many international viewers, the notion that animation could contain such extreme imagery was almost unthinkable. Western audiences, accustomed to animation as a medium for children or adolescent adventure, suddenly encountered a work that combined cinematic brutality with mythology and eroticism. Owning or viewing it became an act of curiosity and defiance. Accessing such media often meant seeking imported tapes or attending small conventions—a process that only heightened its sense of exclusivity and taboo.

Not everyone perceived Urotsukidōji as art. Its reputation became divisive; for some, it represented the most exploitative and grotesque tendencies of Japanese culture, while to others, it was a bold exercise in creative freedom. Regardless of one’s stance, its influence was undeniable. The film inspired countless imitators, establishing a visual and thematic template for subsequent hentai and “erotic horror” animation. Even as later works diversified into comedy, fantasy, and romance, the long shadow of Urotsukidōji remained.

There is also a deeper irony in its legacy. The same adaptation Maeda once criticized expanded the reach and visibility of his creation beyond what any manga publication could have achieved. The collaboration between artist and director—however fraught—produced a convergence of imagination that shaped both the erotic and horror dimensions of modern anime. In a broader sense, it demonstrated that the animated form could explore the same depths of transgression, myth, and existential dread that live-action cinema often reserved for its most daring auteurs.

Seen through this lens, Urotsukidōji becomes more than a piece of pornographic shock cinema. It emerges as a cultural artifact—one that reflects how desire, repression, and fantasy intersect within specific historical and artistic contexts. The work exposes how censorship and creativity can collide to produce unexpected invention, and how audiences, whether through fascination or outrage, help define a genre’s legacy.

For those of my generation, encountering Urotsukidōji was a defining moment that reshaped perception. It suggested that animation could express not only beauty and adventure but also the darker instincts of the human psyche. What began as disbelief evolved into a kind of reluctant respect for its ambition. Beneath the grotesque imagery lay a thematic depth that continues to invite examination—questions about power, violation, and the thin line separating horror from desire.

Today, both Maeda Toshio’s manga and Takayama Hideki’s adaptation occupy a controversial yet essential place in the history of Japanese media. They are remembered not only for their sensational content but for their cultural and aesthetic audacity. The story of Chōjin Densetsu Urotsukidōji endures because it refuses simplification—it is at once abhorrent and visionary, obscene yet strangely philosophical.

From the most ardent anime historian to the casual viewer, its reputation persists. Whether reviled or revered, Urotsukidōji remains the ultimate symbol of hentai’s origins and its infamous reach. It stands as both a warning and a testament: that art, when unfettered by convention and driven by instinct, can explore places society dares not name.