Though the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences claim that the Oscars honor the best of the year, we all know that there are always worthy films and performances that end up getting overlooked. Sometimes, it’s because the competition too fierce. Sometimes, it’s because the film itself was too controversial. Often, it’s just a case of a film’s quality not being fully recognized until years after its initial released. This series of reviews takes a look at the films and performances that should have been nominated but were, for whatever reason, overlooked. These are the Unnominated.

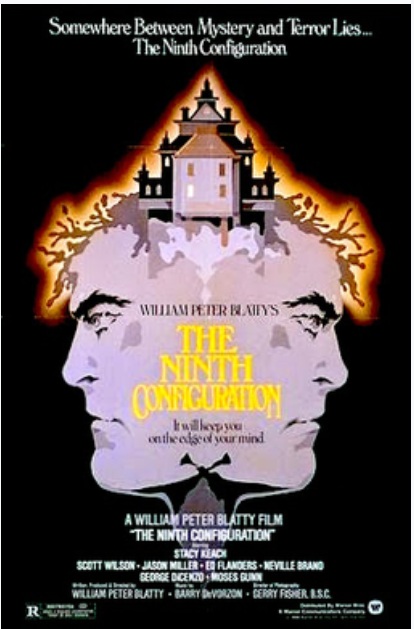

Some films defy easy description and that’s certainly the case with 1980’s The Ninth Configuration.

The film opens with a shot of a castle sitting atop of a fog-shrouded mountain. A voice over tells us that, in the early 70s, the castle was used by the U.S. government to house military personnel who were suffering from mental illness. Inside the castle, the patients appear to be left to their own devices. Lt. Reno (Jason Miller) is trying to teach dog how to perform Shakespeare. Astronaut Billy Cutshaw (Scott Wilson) is haunted by the thought of being alone in space and refuses to reveal why he, at the last minute, refused to go to the moon. The men are watched over by weary and somewhat sinister-look guards, who are played by actors like Joe Spinell and Neville Brand.

Colonel Kane (Stacy Keach) shows up as the new commandant of the the castle. From the first minute that we see Kane, we get the feeling that there might be something off about him. Though he says that his main concern is to help the patients, the man himself seems to be holding back secrets of his own. With the help of Colonel Fell (Ed Flanders, giving an excellent performance), Kane gets to know the patients and the guards. (Despite the objections of the guards, Kane says that his office must always be unlocked and open to anyone who want to see him.) He takes a special interest in Cutsaw and the two frequently debate the existence of God. The formerly religious Cutshaw believes the universe is empty and that leaving Earth means being alone. Kane disagrees and promises that, should he die, he will send proof of the afterlife. At night, though, Kane is haunted by dreams of a soldier who went on a murderous rampage in Vietnam.

The film start out as a broad comedy, with Keach’s smoldering intensity being matched with things like Jason Miller trying to get the dogs to perform Hamlet. As things progress, the film becomes a seriously and thoughtful meditation on belief and faith, with characters like Kane, Billy, and Colonel Fell revealing themselves to be quite different from who the viewer originally assumed them to be. By the time Kane and Cutshaw meet a group of villainous bikers (including Richard Lynch), the film becomes a horror film as we learn what one character is truly capable of doing. The film then ends with a simple and emotional scene, one that is so well-done that it’ll bring tears to the eyes of those who are willing to stick with the entire movie.

Considering all of the tonal shifts, it’s not surprising that the Hollywood studios didn’t know what to make of The Ninth Configuration. The film was written and directed by William Peter Blatty, the man who wrote the novel and the script for The Exorcist. (The Ninth Configuration was itself based on a novel that Blatty wrote before The Exorcist.) By most reports, the studio execs to whom Blatty pitched the project were hoping for another work of shocking horror. Instead, what they got was an enigmatic meditation on belief and redemption. The Ninth Configuration had the same themes as The Exorcist but it dealt with them far differently. (Because he wrote genre fiction, it’s often overlooked that Blatty was one of the best Catholic writers of his time.) In the end, Blatty ended up funding and producing the film himself. That allowed him complete creative control and it also allowed him to make a truly unique and thought-provoking film.

The Ninth Configuration was probably too weird for the Academy. Though it received some Golden Globe nomination, The Ninth Configuration was ignored by the Oscars. Admittedly, 1980 was a strong year and it’s hard to really look at the films that were nominated for Best Picture and say, “That one should be dropped.” Still, one can very much argue that both Blatty’s script and the atmospheric cinematography were unfairly snubbed. As well, it’s a shame that there was no room for either Stacy Keach or Scott Wilson amongst the acting nominee. Keach, to date, has never received an Oscar nomination. Scott Wilson died in 2018, beloved from film lovers but never nominated by the Academy. Both of them give career-best performances in The Ninth Configuration and it’s a shame that there apparently wasn’t any room to honor either one of them.

The Ninth Configuration is not a film for everyone but, if you have the patience, it’s an unforgettable viewing experience.

Previous Entries In The Unnominated: