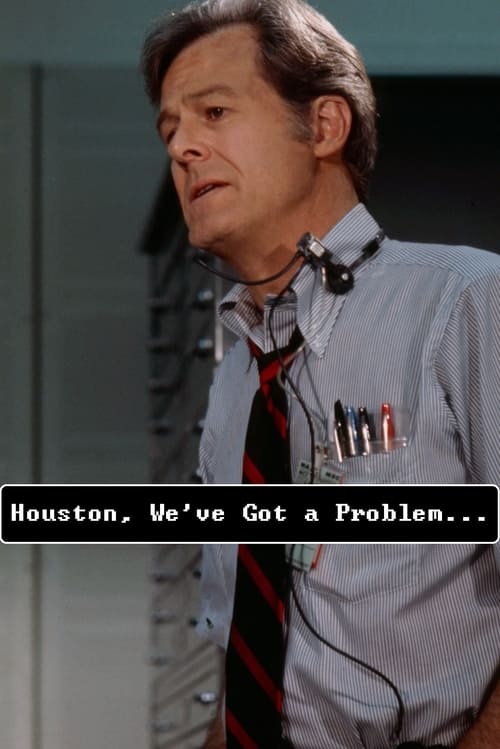

Welcome to Retro Television Reviews, a feature where we review some of our favorite and least favorite shows of the past! On Sundays, I will be reviewing the made-for-television movies that used to be a primetime mainstay. Today’s film is 1974’s Houston, We’ve Got A Problem! It can be viewed on YouTube!

The year is 1970 and Apollo 13 is the latest manned NASA mission into space. The head of the mission of Jim Lovell and the destination is the Moon. Unfortunately, the American public has gotten so used to the idea of men going to the Moon that hardly anyone is paying attention to Apollo 13. That changes when Lovell contacts mission control in Houston and utters those famous words, “Houston …. we’ve had a problem.” An oxygen tank has exploded, crippling the spacecraft and leaving the three men in danger. If Houston can’t figure out how to bring them home, Apollo 13 could turn into an orbiting tomb.

Yes, this film tells the story of the same crisis that Ron Howard recreated in Apollo 13. The difference between Houston, We’ve Got A Problem and Apollo 13 (beyond the fact that one was a big budget Hollywood production and the other a low-budget made-for-TV movie), is that Apollo 13 largely focused on the men trapped in space while Houston, We’ve Got A Problem is totally Earthbound. In fact, Jim Lovell does not even appear in the ’74 film, though his voice is heard. (The film features the actual communications between the crew and Mission Control.) Instead, the entire film follows the men on the ground as, under the leadership of Gene Kranz (Ed Nelson), they try to figure out how to bring the crew of Apollo 13 home. Houston, We’ve Got A Problem is a far more low-key film than Apollo 13, one that features narration from Eli Wallach to give it an effective documentary feel but one that also lacks the moments of wit and emotion that distinguished Apollo 13.

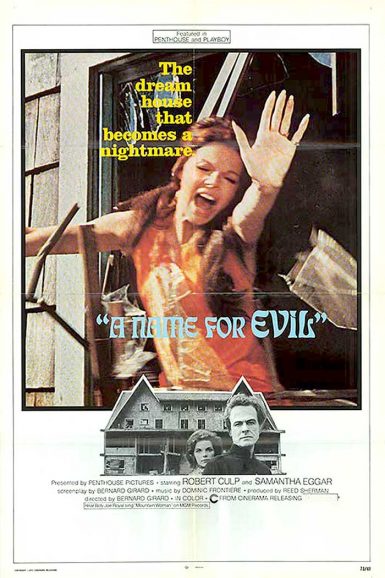

NASA cooperated with the making of the film and it works best when it focuses on the men brainstorming on how to solve the biggest crisis that the American space program had ever faced to that date. The film is less effective when it tries to portray the effects of the men’s work on their home lives. Sandra Dee is wasted as the wife who can’t understand why her engineer husband (reliably bland Gary Collins) can’t spend more time at home. Clu Gulager plays the guy who fears he’s missing out on time with his son. Robert Culp plays the man with a heart condition who places his hand over his chest whenever anything stressful happens. Steve Franken has to choose between his religious obligations and his obligation to NASA. The melodrama of those fictional moments are awkwardly mixed with the based-in-fact moments of everyone calmly and rationally discussing the best way to save the crew. Jim Lovell, as a matter of fact, complained that Houston, We’ve Got A Problem did a disservice to the flight controllers by presenting them all as being hopelessly inept in their lives outside of mission control. (Lovell was reportedly much happier with Apollo 13.)

Because it features the actual conversations between the crew and Mission Control, Houston, We’ve Got A Problem is interesting as a historical document but it never escapes the shadow of Ron Howard’s better-known film.