(With the Oscars scheduled to be awarded on March 4th, I have decided to review at least one Oscar-nominated film a day. These films could be nominees or they could be winners. They could be from this year’s Oscars or they could be a previous year’s nominee! We’ll see how things play out. Today, I take a look at the 1931 best picture winner, Cimarron!)

“Be careful, Hank! Alabaster may be a little dude but he’ll mess you up.”

“No offense … but he’s from Oklahoma.”

— King of the Hill Episode 5.13 “Ho Yeah”

Some best picture winners are better remembered than others. Some, like The Godfather, are films that will be watched and rewatched until the end of time. Others, like Crash, seems to be destined to be continually cited as proof that the Academy often picks the wrong movie. And then you have other films that were apparently a big deal when they were first released but which, in the decades to follow, have fallen into obscurity.

1931’s Cimarron would appear to be a perfect example of the third type of best picture winner.

Based on a novel by Edna Ferber (who would later write another book, Giant, that would be adapted into an Oscar-nominated film), Cimarron is an epic about Oklahoma. The film opens in 1889 with the Oklahoma land rush. Settlers from all across America rush into Oklahoma, searching for a new beginning. Among them is Yancey Cravat (Richard Dix) and his wife, Sabra (Irene Dunne). Yancey is hoping to become a rancher but, upon arriving at the settlement of Osage, he discovers that the land he wanted has already been claimed by Dixie Lee (Estelle Taylor).

So, Yancey gives up on becoming a rancher. Instead, he becomes a newspaper publisher and an occasional outlaw killer. Soon, Yancey and Sabra are two of the most prominent citizens in Osage. Under the guidance of Yancey, Osage goes from being a wild outpost to being a respectable community. It’s not always easy, of course. Criminals like The Kid (William Collier, Jr.) still prey on the weak. As the town grows more respectable, some citizens try to force out people like Dixie Lee. Struck by a combination of personal tragedy and wanderlust, Yancey occasionally leaves Osage but he always seems to return in time to make sure that people do the right thing. When even his wife reveals that she’s prejudiced against Native Americans, Yancey writes a vehement editorial demanding that they be granted full American citizenship.

The film follows Sabra and Yancey all the way to the late 1920s. Oklahoma becomes a state. Sabra becomes a congresswoman. Oil is discovered. Throughout it all, Yancey remains a firm voice in support of always doing the right thing. In fact, he’s such a firm voice that you actually start to get tired of listening to him. Yancey may be a great man but he’s not a particularly interesting one.

By today’s standards, Cimarron is a painfully slow movie. The opening land rush is handled well but once Yancey and Sabra settle down in Osage, the film becomes a bit of a chore to sit through. Richard Dix is a dull lead and the old age makeup that’s put on Dix and Dunne towards the end of the movie is notably unconvincing. Considering some of the other films that were eligible for Best Picture that year — The Front Page, The Public Enemy, Little Caesar, Frankenstein — Cimarron seems even more out-of-place as an Oscar winner.

And yet, back in 1931, it would appear the Cimarron was a really big deal. Consider this:

Cimarron was not only well-reviewed but also a considerable box office success.

Cimarron was the first film to ever receive more than 6 Academy Award nominations. (It received seven and won 3 — Picture, Screenplay, and Art Direction.)

Cimarron was the first film to be nominated in all of the Big Five categories (Picture, Actor, Actress, Director, and Screenplay).

Cimarron was the first film to be nominated in every category for which it was eligible.

Cimarron was the first RKO film to win Best Picture. The second and last RKO film to win would be The Best Years of Our Lives, a film that has held up considerably better than Cimarron.

Cimarron was the first Western to win Best Picture. In fact, it would be 59 years before another western took the top award.

Though Cimarron may now be best known to those of us who watch TCM, it’s apparent that it was a pretty big deal when it was first released. Though it seems pretty creaky by today’s standards, they loved it in 1931.

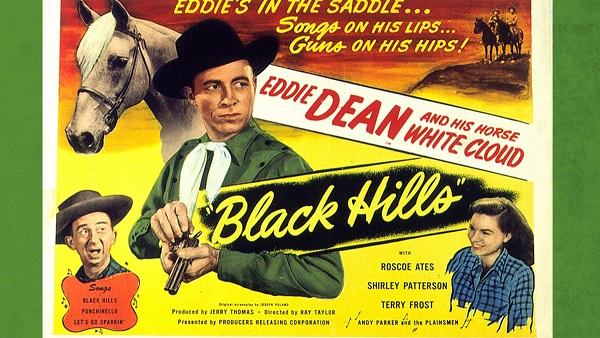

Singing Ranger Eddie Dean (played by the same-named Eddie Dean) and his sidekick, Soapy Jones (Roscoe Ates), are sent to track down the Tioga Kid, an outlaw who happens to look just like Eddie. Soapy suggests that The Tioga Kid could be a long lost twin brother. Eddie isn’t sure because his parents were killed in an Indian ambush when he was just a baby. This seemed to be the backstory for many of Poverty Row’s favorite western heroes.

Singing Ranger Eddie Dean (played by the same-named Eddie Dean) and his sidekick, Soapy Jones (Roscoe Ates), are sent to track down the Tioga Kid, an outlaw who happens to look just like Eddie. Soapy suggests that The Tioga Kid could be a long lost twin brother. Eddie isn’t sure because his parents were killed in an Indian ambush when he was just a baby. This seemed to be the backstory for many of Poverty Row’s favorite western heroes.