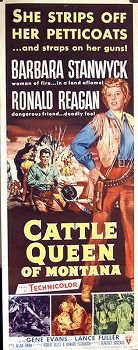

Pop Jones (Morris Ankurm) and his daughter Sierra Nevada (Barbara Stanwyck) leave their ranch in Texas and head up to Montana to take over some land that Pop has inherited. Evil Tom McCord (Gene Evans) wants the land for himself and conspires with a member of the local Blackfoot tribe, Natchakoa (Tony Caruso), to take it over. After a surprise attack leaves Pop dead, Sierra is nursed back to health by Colorados (Lance Fuller), the son of the Blackfoot chief. Sierra tries to reclaim her land from McCord, with the eventual help of the mysterious gunslinger Farrell (Ronald Reagan).

Pop Jones (Morris Ankurm) and his daughter Sierra Nevada (Barbara Stanwyck) leave their ranch in Texas and head up to Montana to take over some land that Pop has inherited. Evil Tom McCord (Gene Evans) wants the land for himself and conspires with a member of the local Blackfoot tribe, Natchakoa (Tony Caruso), to take it over. After a surprise attack leaves Pop dead, Sierra is nursed back to health by Colorados (Lance Fuller), the son of the Blackfoot chief. Sierra tries to reclaim her land from McCord, with the eventual help of the mysterious gunslinger Farrell (Ronald Reagan).

There are a lot of reasons why this B-western doesn’t really work, a huge one of them being that Barbara Stanwyck was several years too old to be playing Morris Ankrum’s innocent daughter. The biggest problem though was casting Ronald Reagan as a mysterious gunslinger. Farrell is a character who is supposed to keep us guessing. We’re not supposed to know if he’s a good guy or a bad guy. But as soon as Ronald Reagan shows up and starts to speak, we know everything we need to know about Farrell. There was nothing enigmatic or even dangerous about Ronald Reagan’s screen persona. He came across as being more open and honest as just about any other actor from Hollywood’s Golden Age. For the role of Farrell, it appears that he went a day without shaving and he tried not to smile while on-camera but he’s still good old dependable Ronald Reagan. That pleasantness and lack of danger may have kept him from becoming an enduring movie star but it did serve him very well when he moved into the political arena.

Cattle Queen of Montana was one of the 200 westerns that Allan Dwan directed over his long career. It’s not one of his more interesting films, though he does manage a few good action sequences. A far better Dwan/Reagan collaboration was Tennessee’s Partner, which was released four years after this film.