In 1950’s The Jackpot, James Stewart plays Bill Lawrence.

Bill has a job at a department store. He’s not the manager but he’s still a respected member of the staff and who knows? Maybe his boss (Fred Clark) will give him a promotion someday. He lives in a big, two-story home with his wife, Amy (Barbara Hale). He and Amy have two children, one of whom is played by a 12 year-old Natalie Wood. By all appearances, Bill is doing pretty good for himself. At one point, it’s mentioned that makes a grand total of $7,500 a year.

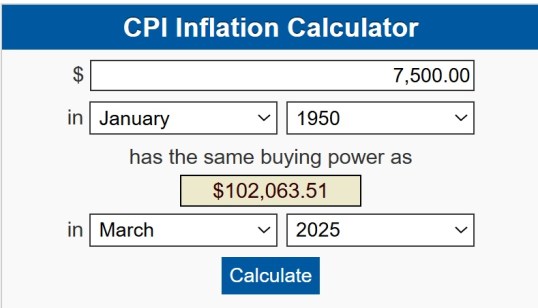

That definitely caught my attention. “I make more than that!” I snapped at the screen. I pulled up an inflation calculator and I discovered that $7,5000 in 1950 is the equivalent of — wait for it — $102,000 today! (Technically, I still make more than that but still, it’s six figures.)

When Bill answers a phone call from a radio station and guesses the correct answer to a trivia question, he wins $24,000-worth of prizes. (I didn’t bother to figure out how much that $24,000 would be be in 2025 dollars but we can safely assume that it would be quite a bit.) Unfortunately, a lot of the prizes end up costing more than their worth. Bill wins a side of beef , 7,500 cans of soup, and a 1,000 fruit trees but he doesn’t win anywhere to store it all. He also wins a maid, an interior designer, a pony, a swimming pool, a trip to New York, and a session with portrait painter Hilda (Patricia Medina). He also ends up with an income tax bill for $7,000. Remember, he only makes $7,500 a year. Damn the IRS!

Realizing that he’s going to have to sell the majority of his winnings, Bill loses his job when he’s caught trying to sell to the store’s customers. Needing money to pay off his tax bill, he tries to pawn a diamond ring and ends up getting arrested. With his anniversary coming up, he asks Hilda to paint a portrait of Amy from his description of her but Bill ends up spending so much time with Hilda that Amy becomes convinced that he’s having an affair.

Basically, one terrible thing after another happens to Bill, all the result of having won a contest. (The film is loosely based on a true story, with James Gleason playing a fictionalized version of the reporter who wrote the original story.) The movie’s a comedy but, as with the majority of the films that James Stewart made after World War II, there’s a sense of melancholy running through it. Even before he wins the money, Bill doesn’t seem satisfied with his life. Much like George Bailey, he’s restless and wondering if there will ever be more to his life than just his house in the suburbs and his job in the city. Also, like George, Bill learns to appreciate what he has as the result of getting what he wants and discovering that he was happier before. Few actors were as skilled at capturing ennui and dissatisfaction as Jimmy Stewart. The Jackpot is a silly comedy but it’s also an effective portrait of a middle-aged man trying to find peace with the way his life has turned out. That’s almost entirely due to Stewart’s likable but honest performance.

The Jackpot may not be one of Stewart’s most-remembered films but it’s entertaining, with the supporting cast all providing their share of laughs while Stewart provides the film with a heart. The film may be a comedy but it’s also a look at America and Americans adjusting to life in the years immediately following World War II. Suddenly, abundance is everywhere but, as Bill Lawrence, not without a price.