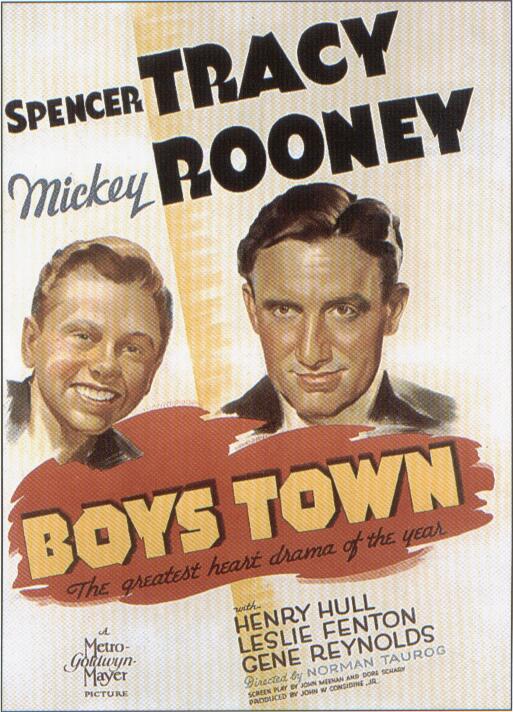

Before writing about the 1938 film Boys Town, I want to share a story that might be false but it’s still a nice little story. Call this an Oscar Urban Legend:

Boys Town is about a real-life community in Nebraska, a home for orphaned and homeless boys that was started by Father Edward Flanagan. In the film, which was made while Father Flanagan was still very much alive, he was played by Spencer Tracy. Boys Town was a huge box office success that led to the real Boys Town receiving a lot of favorable publicity. When Tracy won his Oscar for Boys Town, his entire acceptance speech was devoted to Father Flanagan.

However, a problem arose when an overeager PR person at MGM announced that Spencer Tracy would be donating his Oscar to Boys Town. Tracy didn’t want to give away his Oscar. He felt that he had earned it through his acting and that he should be able to keep it. Tracy, the legend continues, was eventually persuaded to donate his Oscar on the condition that he would get a replacement.

However, when the replacement arrived, the engraving on the award read, “Best Actor — Dick Tracy.”

That’s a fun little story, one that is at least partially true. (Tracy’s Oscar — or at least one of them — does currently reside at the Boys Town national headquarters.) It’s also a story that, in many ways, is more interesting than the film itself.

Don’t get me wrong. Boys Town is not a bad movie. For me, it was kind of nice to see a movie where a priest was portrayed positively as opposed to being accused of being a pederast. In a way, Boys Town serves as a nice counterbalance to Spotlight. But, with all that said, there’s not a surprising moment to be found in Boys Town. It’s pretty much a standard 1930s juvenile delinquency melodrama.

The movie opens when Father Flanagan giving last rites to a man who is about to be executed. (Boys Town takes a firm stand against the death penalty, which is one of the more consistent and laudable stands of the modern Church.) The man says the he never had a chance. From the time he was a young boy, he was thrown into the reform school system. Instead of being reformed, he just learned how to be a better criminal. Father Flanagan is so moved by the doomed man’s words that he starts Boys Town, under the assumption that “there’s no such thing as a bad boy.”

Father Flanagan’s techniques are put to the test when Whitey Marsh (Mickey Rooney ) arrives. Whitey is angry. He’s rebellious. He tries to run away every chance that he gets and, during one such escape attempt, he even gets caught up in a bank robbery. Can Father Flanagan reach Whitey and prove that there’s no such thing as a bad boy?

Well, you already know the answer to that. As I said, there’s really nothing surprising to be found in the plot of Boys Town. It’s just not a very interesting movie, though there is a great shot of a despondent Whitey walking past a several lines of former juvenile delinquents, all kneeling in prayer. As Father Flanagan, Spencer Tracy is the ideal priest but his role is almost a supporting one. Believe it or not, the film is dominated by Mickey Rooney, who gives a raw and edgy performance as the angry Whitey Marsh.

(That said, it’s hard to take Whitey seriously as a future gangster when he’s always wearing a bowtie. Then again, that may have been the height of gangster style in 1938.)

Boys Town was nominated for best picture but lost to You Can’t Take It With You.

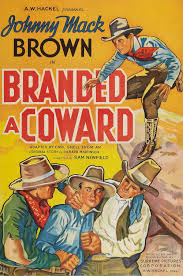

When Johnny Hume was just a young boy, he witnessed his entire family being killed by a group of bandits led by the mysterious Cat. Johnny grows up to be a trick-shot artist but, despite his skill with a gun, he can’t stand to point it at anyone or to be near any sort of gunfights. When a fight breaks out in a saloon, he hides behind a bar and is labeled a coward.

When Johnny Hume was just a young boy, he witnessed his entire family being killed by a group of bandits led by the mysterious Cat. Johnny grows up to be a trick-shot artist but, despite his skill with a gun, he can’t stand to point it at anyone or to be near any sort of gunfights. When a fight breaks out in a saloon, he hides behind a bar and is labeled a coward.