After watching Inherent Vice last weekend, I decided to get on Netflix and do a search for film noirs. This led to me watching four film noirs from the 50s, all of which were previously unknown to me.

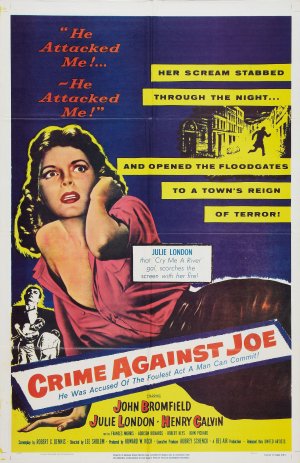

For my first Netflix Noir, I watched a little something called Crime Against Joe. It’s a 69 minute film from 1956. It’s about a guy named Joe. There’s been a crime. Oddly enough, the crime really against Joe. Instead, he’s been wrongly accused of committing a crime against a nightclub singer named Irene. So, perhaps a better title for this film would have been It Sucks To Be Joe.

But anyway —

Crime Against Joe was directed by Lee Sholem. According to Wikipedia, Lee Sholem had a 40 year career as a director. During that time, he directed over 1,300 television episodes and feature films and he finished every single one of them either on time or early. And you can certainly see evidence of that in Crime Against Joe, a film that starts out in a rush and pretty much never slows down until the final fade out.

Joe (John Bromfeld) was voted “most likely to succeed” in high school but — surprise! surprise! — he’s failed to live up to the expectations set for him by the 1945 yearbook. Instead, he enlisted in the army, served in the Korean War, and was diagnosed with “battle fatigue.” (I assume that battle fatigue was the 1950s version of PTSD.) He spent a while in a mental hospital and it was there that he first started painting. When he was released, he moved in with his widowed mother (Frances Morris). While she works to support him, Joe spends his time drinking and painting.

As the movie begins, a drunken Joe has just destroyed his latest painting. (“I can see it in my head but it doesn’t come out on canvas!” Joe shouts, which is actually a pretty good way to describe the dark feeling that all artists occasionally get.) He wanders around town, drunk. He talks to a waitress named Slacks (Julie London), who is obviously in love with him. He gets some sage advice from Red (Henry Calvin), a taxi driver. He stumbles into a nightclub where he harasses a singer (Alika Louis) before finally getting thrown out of the club. In the parking lot, as he stumbles away, a mysterious cowboy (Rhodes Reason) glares at him.

Joe stumbles about until, around two in the morning, he runs into a young woman wearing a nightgown. He tries to talk to her but she only stares at him, her placid face frozen in a zombie-like state. Joe leads her to a nearby house where the woman’s father thanks him for his help and then slams the door in his face.

Later that night, the nightclub singer is found dead on the side of the road. Found near her body is a high school pin that belonged to someone from the class of 1945. Knowing that Joe was drunk that night and had been seen in the nightclub, Detective Hollander (Robert Keys) goes to Joe’s house. Hollander demands to see Joe’s high school pin. Joe says he doesn’t know where it is. Hollander stares at Joe’s paintings. “You always paint half-naked women?” Hollander sneers before arresting Joe for murder.

At the station, Joe says that he was leading the woman back to her house at the same time that the singer was murdered. The woman’s father shows up at the police station. No, he says, Joe was nowhere near his house at two in the morning. Joe is arrested for murder…

Fortunately, Slacks is willing to risk her life to prove that Joe is innocent. And Joe knows that the murderer had to have been someone who he went to high school with…

Crime Against Joe is one of those low-budget, obscure B-movies that actually a lot more interesting than you might think. John Bromfeld does a good job as Joe and the character’s PSTD gives the film a bit more depth than you might otherwise expect. Julie London is great in the role of brave and selfless Slacks (though it’s interesting that this film felt the need to give a masculine nickname to a strong female character) and Rhodes Reason is genuinely menacing as the mysterious cowboy. Crime Against Joe is also full of unexpected and occasionally surreal details. The most obvious example would be the zombie-like woman who Joe runs into on the night of the murder. However, my favorite little oddity is the fact that signs reading “Corey for Councilman” keep popping up in the strangest locations.

(It eventually turns out that Joe went to high school with Corey and the scene where Joe confronts his old classmate is a fun little piece of political satire. That said, there was a part of me that hoped the significance of the sings would just remain an odd and unexplained little detail.)

There’s actually a surprisingly subversive streak running through Crime Against Joe. We usually tend to think of the 50s as being a time when authority figures (like the police) were viewed with blind trust. In Crime Against Joe, however, nobody in power is portrayed positively. The police, for instance, come across like a bunch of close-minded bullies who are prepared to convict Joe based solely on his paintings and his less-than-sterling war record. The scenes where Hollander interrogates Joe are full of menace. In the end, this film is on the side of those living on the margins of respectable society. When Joe and Slacks try to prove Joe’s innocence, they’re also attempting to prove their own right to exist in a society that has rejected both of them.

Crime Against Joe may not be a well-known film but there’s a lot more going on under its surface than you might originally think. It’s on Netflix so check it out when you’ve got 70 minutes to spare.