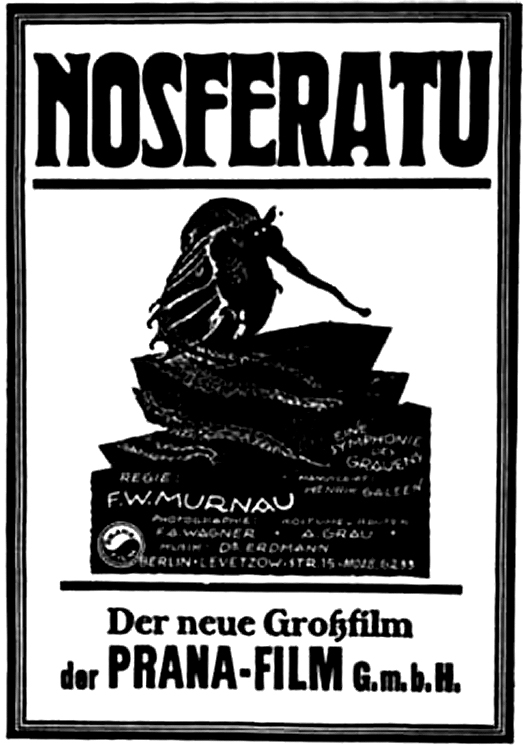

First released in 1922, the original and silent Nosferatu remains a masterpiece.

The story …. well, we all know that story. Even if you’ve never seen any of three film versions of Nosferatu, you still know the story because it’s basically just Dracula with the names and the locations change. Dracula is now Count Orlok (Max Schreck), a mysterious nobleman with bat-like features and a fascination with blood. Jonathan Harker, the estate agent who traveled from England to Transylvania to visit with Dracula, is now Thomas Hutter (Gustav van Wangenheim), a real estate agent who travels from Germany to Transylvania to see Count Orlok. The mad, bug-eating Renfield is now the mad, bug-eating Knock (Alexander Granach). Mina Harker is now Ellen (Greta Schroder). Prof. Van Helsing is now Professor Bulwer (John Gottowt). Dracula came to England aboard the Demeter. Count Orlok comes to Germany about the Empusa.

There are a few differences, of course. Director F.W. Murnau may have used Dracula as his starting point but he brought his own ideas and sensibility to the project as well. In Nosferatu, Orlok received his vampiric powers from the demon Belial and he not only drinks blood but he also brings with him the threat of plague. The Empusa brings not just Orlok but also thousands of rats who spread disease in the German town of Wisburg. The town, which is so vibrant during the early parts of the film, soon becomes a dark and ominous place where the people blame Knock for every curse the Orlok has brought to them. If Dracula could be destroyed by a stake to the heart and stopped by a cross, Orlok can be stopped by a pure woman sacrificing herself and allowing him to drink her blood as the sun rises. Orlok, for all of his feral cleverness, cannot resist the twin temptation of blood and innocence. It leads to an ending that’s quite a bit different from the ending of Bram Stoker’s novel. In Werner Herzog’s 1979 remake of the film, the insinuation was that the town itself was not worth the sacrifice. F.W. Murnau is far less cynical.

Typically, it takes some effort to adjust to watching a silent movie. Everything from the frequently melodramatic title cards to the overly expressive acting can tend to make silent cinema seem more than a little campy. Nosferatu, however, requires less adjustment than most because it’s a film that it still being imitated to this day. The images of Orlok standing on the bridge of the ship or slowly entering Hutter’s room or leaning down over Ellen’s neck are so haunting and dream-like that it doesn’t matter that they are found in a silent film. Fear is the universal language and Murnau’s visuals still carry a lot of power.

Made at a time when the world was still recovering from the carnage of the First World War, Nosferatu perfectly captures the feeling of innocence and optimism being replaced by despair and paranoia. It’s been argued that Nosferatu reflected the fears and anxieties of post-war German society, with the vampire representing the fear of Germany being taken over by outside forces. There’s probably something to that. Tragically, those fears also led to the rise of Hitler so I’ll just say that the majority of the cast of Nosferatu fled Germany when Hitler came to power. John Gottowt, the film’s version of Van Helsing, was murdered by the SS. Director F.W. Murnau died in a car accident before Hitler came to power but, as a gay man, he would not have been welcome in Hitler’s Germany.

The film itself was a hit when it was first released in Germany. Unfortunately, calling the vampire Orlok instead of Dracula did not dissuade Bram Stoker’s widow from suing for copyright infringement. Mrs. Stoker won her case and all copies of Nosferatu were ordered destroyed. Fortunately, a few prints survived and Nosferatu continues to be regarded as one of the greatest horror films ever made.