4 Shots From 4 Films is just what it says it is, 4 shots from 4 of our favorite films. As opposed to the reviews and recaps that we usually post, 4 Shots From 4 Films is all about letting the visuals do the talking.

4 Shots From 4 Films

4 Shots From 4 Films is just what it says it is, 4 shots from 4 of our favorite films. As opposed to the reviews and recaps that we usually post, 4 Shots From 4 Films is all about letting the visuals do the talking.

4 Shots From 4 Films

While the goth ballerina side of me will always have a special place in my heart for Suspiria and its two sequels, I think that 1982’s Tenebrae may very well be director Dario Argento’s best film. Certainly, it was (to date) his last truly great film before he entered the current, frustratingly uneven stage of his career.

Tenebrae was a return to Argento’s giallo roots after the supernatural-themed horror of Suspiria, Zombi, and Inferno. It was also the work of an audaciously confident director. That confidence is fully on display in the scene below in which the film’s killer menaces a journalist and her lover. Featuring a truly impressive tracking shot in which the camera appears to literally swoop in, out, and over a journalists house without a single cut, the scene ends with one of Argento’s more memorable murders.

The music, by the way, is from Goblin.

Because I’m not real certain that I’ll be online this weekend (well, that plus the fact that I love you), I’m posting the latest installment of Lisa Marie’s favorite grindhouse and exploitation trailers a few days early. Enjoy!

1) Scream and Scream Again — This is actually a pretty good British horror film from 1970. It even has a political subtext for those of you who need your horror to mean something. I love the whole “swinging” vibe of the trailer.

2) The Spook Who Sat By The Door — This 1973 film apparently used to be something of a legend because it was extremely difficult to see. It was sold, obviously, as a blaxploitation film but quite a few people apparently saw it as being a blueprint for an actual revolution. I’ve never seen this movie though, believe it or not, I did find a copy of the novel it was based on at Half-Priced books shortly after I first saw this trailer. I bought the book but I haven’t read it yet.

3) The Black Gestapo — This is another one of those old school blaxploitation trailers that, to modern eyes, just seems so wrong. I’ve actually seen this film. It’s surprisingly dull, to be honest.

4) Sunset Cove — This one of the many trailers that I first came across on one of Synapse’s 42nd Street Forever compilations. I’ve never seen the actual film and probably never will as apparently it’s like the uncut version of Greed — lost to the ages. That’s okay because the film really does look really, really bad. However, the trailer fascinates me because it has got such an oddly somber tone to it. Just from the narration and one or two of the clips shown, you get the feeling that this movie ends with the National Guard gunning down a lot of teenagers while the tide comes in. However, I think that might just be my own overactive imagination. The film was apparently directed by Al Adamson who, in the mid-90s, was apparently murdered and buried in wet cement.

5) Autopsy — This 1975 Italian classic is one of my favorite examples of the giallo genre. I can’t recommend it enough. This is one of the most intense and disturbing films ever made. The trailer’s pretty good too.

6) Visiting Hours — I don’t know much about this movie, other than it appears to be a slasher film from the early 80s. I’m posting it here for one reason and one reason only — the skull.

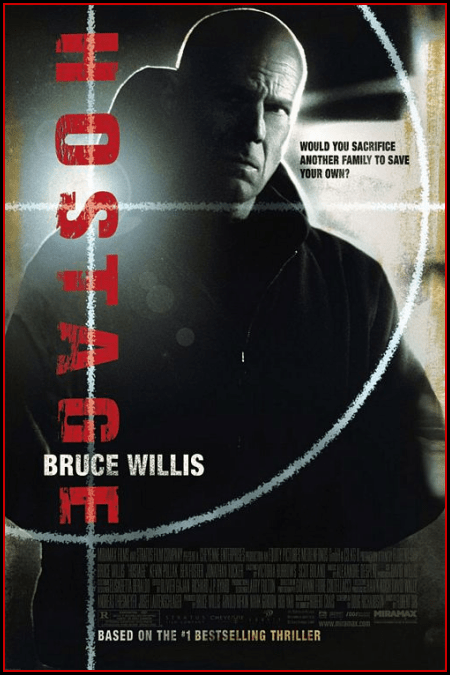

The five years or so has seen the rise of several new directors from France who’ve made quite a splash with their Hollywood debuts. There’s Alejandro Aja with Haute Tension (or Switchblade Romance/High Tension) who brought back the late 70’s early 80’s sensibilities of what constitutes a good slasher, exploitation film. Then there’s Jean-Francois Richet whose 2005 remake of John Carpenter’s early classic, Assault on Precinct 13 surprised quite a bit in the industry. Neither film made too much in terms of box-office, but they did show that a new wave of genre directors may not be coming out of the US but from France of all places. Another name to add to this list is Florent Siri and his first major Hollywood project Hostage shows that he has the style and skills to make it in Hollywood.

Hostage is another Bruce Willis vehicle that was adapted by Doug Richardson (wrote the screenplay for Die Hard 2) from Robert Crais’ novel. Hostage is a very good thriller with a unique twist to the hostage-theme. Willis’ character is a burn-out ex-L.A. SWAT prime hostage negotiator whose last major case quickly ended up in the death of suspect and hostages. We next see him as chief of police of a small, Northern California community where low-crime is the norm. We soon find out that his peace of mind and guilt from his last case may have eased since taking this new job, but his family life has suffered as a consequence. All of the peace and tranquility is quickly shattered as a trio of local teen hoodlums break into the opulent home of one Walter Smith (played by Kevin Pollak). What is originally an attempt to steal one of the Smith’s expensive rides turn into a hostage situation as mistakes after mistakes are made by the teens.

From this moment on Hostage would’ve turned into a by-the-numbers hostage thriller, but Richardson’s screenplay ratchets things up by forcing Willis’ character back into the negotiator’s role as shadowy character who remain hooded and faceless throughout the film kidnap his wife and daughter. It would seem that these individuals want something from the Smith’s home and would kill Willis’ character’s family to achieve their goals. The situation does get a bit convoluted at times and the final reel of the film ends just too nicely after what everyone goes through the first two-third’s of the film.

The character development in the film were done well enough to give each individual a specific motivation and enough backstory to explain why they ended up in the situation they’ve gotten themselves into. Willis’ performance in Hostage was actually one of better ones in the last couple years. The weariness he gives off during the film was more due to his character’s state of mind rather than Willis phoning in his performance. I would dare say that his role as Chief of Police Jeff Talley was his best in the last five years or so. The other performance that stands out has to be Ben Foster as the teen sociopath Mars. Foster’s performance straddles the line between being comedic and over-the-top and could’ve landed on either side. What we get instead is one creepy individual who almost becomes the boogeyman of the film. In fact, the last twenty minutes of Hostage makes Mars into a slasher-film type character who can’t seem to die.

The real star of the film has to be Florent Siri’s direction and sense of style. From the very first frame all the way to the last, Siri gives Hostage the classic 70’s and 80’s Italian giallo look and feel. Siri’s use of bright primary colors in conjuction with the earthy, desaturated look of the film reminds me of some of the best work of Argento, Bava and Fulci. In particular, Siri’s film owes alot of its look to films such as Tenebrae, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, and The Psychic. Certain scenes, especially the penultimate climax in the Smith home, take on an almost dreamlike quality. Siri’s homage to the classic gialli even gives Hostage some sequences that would comfortably fit in a 70’s slasher film.

Florent Siri’s Hostage is not a perfect film and at times its increasing tension without any form of release can be unbearable to some people, but it succeeds well enough as a thriller. It also shows that Siri knows his craft well and instead of mimicking and cloning scenes from the gialli he’s fond of, he emulates and adds his own brushstrokes. The film is not for everyone and some people may find the story convoluted if not dull at times, but for me the film works well overall. Siri is one director that people should keep an eye on.

If you’re lucky, you remember your first time. I know I do. I was 17 years old and I was trying very hard to convince myself that I was an adult. It had been less than a year since I was first diagnosed as being bipolar and I was still struggling to understand what that truly meant about me. My days were spent wondering if I was crazy or if I was just misunderstood. In the end, I just desperately wanted to be loved. As for the event itself, I remember being more than a little anxious and, once things really got going, pleasantly surprised. However, the main thing I remember is thinking to myself, “Wow, that’s a lot of blood.”

Yes, everyone should remember the experience of seeing their first giallo as clearly as I do.

Over the years, I’ve read a lot of different definitions of what a giallo is and none of them have really managed to capture what makes this genre of film so strangely compelling. The simplest and quickest definition is that a giallo is an Italian thriller. Typically (though not always), the film features a protagonist who witnesses and then proceeds to investigate a series of increasingly gory murders. Often times, solving the murders means uncovering some dark and sordid sin of the past and, just as often, the film’s “hero” turns out to be as damaged a soul as the killer. However, the plot is rarely the important in a giallo film. What’s important is how the director chooses to tell the story. When I watch the classic giallo films of the 60s and 70s, I get a sense of a small group of directors who were all competing to say who could come up with the most startling camera angle, who could pull off the bloodiest death scene, and who could pull off the most audacious tracking shot. Giallo is a uniquely Italian genre of film, an unapologetic opera of mayhem and murder. For the most part, the films seems to have a polarizing effect on viewers. You either get them or you don’t. (From my own personal experience, I think it helps if you come from a Catholic background but, again, that’s just my opinion.)

My first giallo was Lamberto Bava’s 1983 shocker, A Blade in the Dark.

The protagonist of A Blade in the Dark is Bruno, a popular young composer who has been hired to score a horror movie. The film’s director has arranged for Bruno to stay in an isolated villa while he works. Every night, Bruno sits in front of his piano and searches for the perfect note. Occasionally, his actress girlfriend calls him from the other side of Italy and demands to know if he’s cheating on her. He’s not despite the fact that he has two attractive neighbors who tend to come by at the most inconvenient of times and who make cryptic comments about the woman who lived at the villa before him. Bruno would probably be even more frustrated if he knew that, on most night, he’s being watched by someone outside hiding outside the villa. One night, Bruno listens to the movie’s soundtrack and hears a menacing voice whispering on the recording. Meanwhile, the mysterious watcher begins to brutally murder anyone who has any contact with Bruno.

(Despite all these distractions, Bruno continues to vainly try to create the perfect score. Much like Kubrick’s Shining, A Blade in the Dark is as much about the horrors of the artistic process as it is about anything else.)

As it typical of most giallo films, the plot of A Blade in the Dark makes less and less sense the more that you think about it. However, this is a part of the genre’s charm. One doesn’t watch a giallo for the story. One watches to see how the story is told and that is where A Blade in the Dark triumphs. Wisely, director Lamberto Bava keeps things simple. Working with a small cast and one main set, Bava fills every scene with a palpable sense of dread and uneasiness. As Bruno finds himself growing more and more paranoid, so does the audience. Watching the movie, you feel that anyone on the screen could die at any moment and, for the most part, that turns out to be the case.

A Blade in the Dark is probably best known for the brutality of its violence. Even after repeat viewings, the murders are still, at times, difficult to watch. In the most infamous of them, one of Bruno’s neighbors is killed while washing her hair over a sink. The violence here is so sudden and so much blood is spilled (and spurted) that its easy to miss just how well-directed and effectively shocking this scene really is. In this current age of generic cinematic mayhem, the violence of A Blade In The Dark still packs a powerful punch.

(The scene is so effective that, for quite some time after seeing it, I actually got uneasy whenever I found myself standing in front of a sink. A Blade in the Dark does for the bathroom sink what Psycho did for showers.)

Bruno is played by Andrea Occhipinti, an actor whose non-threatening, Jonas Brotheresque handsome earnestness was used to great effect by Lucio Fulci in the earlier New York Ripper. Since I’ve only seen the dubbed version, it’s difficult to judge his performance here. He’s never quite believable as a great composer though you could easily imagine him writing whatever syrupy ballad that James Cameron chooses to play at the end of his next blockbuster. However, Occhipinti does have a likable enough presence that you don’t want to see him killed and that’s all that the film really requires anyway.

A far more interesting presence in the cast is that of Michele Soavi. Soavi plays Bruno’s landlord and, even with limited screen time and even with his dialogue dubbed into English, Soavi is such a charismatic presence that he dominates every scene that he’s in. Before being cast, Soavi was already serving as Bava’s assistant director on Blade in the Dark and, of course, he later went on to have a significant directorial career of his own. Soavi is perhaps best known for directing one of the greatest films of the 1990s, Dellamorte Dellamore.

While Soavi would go on to great acclaim, the same cannot be said of this movie’s director. Among fans of Italian horror, it’s become somewhat fashionable to be dismissive of Lamberto Bava. It’s often pointed out that the majority of his filmography is actually made up of cheap knock-offs that he made for Italian television (and, admittedly, A Blade in the Dark started life as a proposed miniseries). Most of the credit for Bava’s most succesful film — Demons — is usually given to producer Dario Argento. Perhaps the most common complaint made about Lamberto Bava is that he isn’t his father, Mario Bava. With films like Blood and Black Lace, Lisa and the Devil, Black Sabbath, and Bay of Blood, Mario Bava developed a deserved reputation for being the father of Italian horror and Lamberto is often accused of simply trading in on his father’s reputation.

It’s true that Lamberto Bava is no Mario Bava but then again, who is? Blade in the Dark was Lamberto’s second film (as a director) and its a tightly constructed, quickly paced thriller. Bava makes good use of the vila and creates a truly claustrophobic atmosphere that keeps the viewer on edge throughout the entire film. Even when viewed nearly three decades after they were filmed, the film’s murders are still shocking in both their violence and their intensity. There’s a passion and attention-to-detail in Bava’s direction here that, sadly, is definitely lacking in his later films. If most of Bava’s film seem to be the work of a disinterested craftsman, A Blade in the Dark is the work of an artist.

I’ve decided to share my love of grindhouse films by posting periodical daily grindhouse choices. To inaugurate this new feature I’ve chosen a favorite early 80’s grindhouse flick straight from the mind of the maestro himself, Lucio Fulci.

The New York Ripper is one of Fulci’s contribution to the Italian cinema genre of gialli films. Giallo (gialli – plural) films have a colorful, no pun intended, history in Italian filmmaking and it’s Golden Age last from the 70’s all through the mid-80’s when the public’s appetite for them started to wane. This Lucio Fulci entry into the giallo genre was not his first but it was one of his most infamous one’s for the fact that many people thought it’s depiction of women and their deaths on-screen was labeled as extremely misogynistic and cruel. The New York Ripper wasn’t even one of the better films in Fulci body of work, but the label of misogynism and having been banned from many countries or being shown only as a X-rated feature film brought it attention and made it a staple in the so-called “grindhouse” cinemas that were prevalent in the 70’s and 80’s.

The film liberally lifts its ideas from the famous “Jack the Ripper” true-crime investigation and transplants it, where else, but New York City. The killings were brutal to the point that I understood the outrage many had over them. What made this film a favorite of mine is not the controversy revolving over calls of misogynism or the near-pornographic scenes of violence, but the killer himself. As you shall see in the attached trailer for the film the duck voice and quacking you will hear is not a joke added into the trailer but part of the film’s titular character’s personality.

Yes, ladies and gents…Donald Duck is the New York Ripper!