(SPOILERS BELOW! THE END OF THIS FILM WILL BE REVEALED! I will also be revealing who played George Gibbs but that’s probably not as big a spoiler. It depends how you look at it.)

I was only 15 years old when I first read Our Town. Because I was a theater nerd, I knew a little about the play. For instance, I knew it took place in a small town. I knew that it was narrated by a character known as the Stage Manager. I knew that the play was meant to be performed on a bare stage, with no sets or props. What I did not know, as I innocently opened up that booklet, is that Our Town is probably one of the most traumatically depressing plays ever written.

When the stage manager appears at the start of the play and talks about the town of Grover’s Corner, he lulls you into believing that you’re about to see a sentimental, comedic, and old-fashioned celebration of small town life. We meet the characters and they all seem to be quirky in a properly non-threatening way. Joe Crowell shows up delivers a newspaper to Doc Gibbs. The stage manager mentions that Joe will eventually grow up to attend to M.I.T.

“Awwwww! Good for Joe!” the audience says.

And, the Stage Manager goes on to inform us, as soon as Joe graduates, he will be killed in World War I, his expensive education wasted.

Okay, the audience thinks, that was a dark moment but this play was written at a time when World War I was still fresh on everyone’s mind. Surely the rest of the play will not be quite as dark…

And fortunately, George Gibbs and Emily Webb show up. They’re young, they’re likable, and they’re in love! George and Emily get married and they’re prepared to live a long and happy life in our town! Good for them! YAY!

And then Act III begins…

Oh my God, Act III. Act III begins with almost everyone dead. Emily died in child birth so she hangs out at the local cemetery and talks to all the other dead people, the majority of whom only have vague memories of their former lives. Emily relives the day of her 12th birthday and discovers that it’s too painful to remember what it was like to once be alive. Emily asks the Stage Manager if anyone truly appreciates life. The Stage Manager replies, “No.” In the world of the living, George Gibbs sobs over his wife’s grave….

And the play ends!

OH MY GOD!

Seriously, reading Our Town was probably one of the most traumatic experiences of my life!

The 1940 film version of Our Town is a little less traumatic because it changes the ending. In the film version, Emily doesn’t die. She nearly dies while giving birth to her second child and the entire third act of the play is basically portrayed as being a near-death hallucination. But, in the end, she survives and she comes through the experience with a new found appreciation for life.

And it’s certainly the type of happy ending that I was hoping for when I first read the play but, as much as I hate to admit it, the story works better with Emily dying than with Emily surviving. The play presents death as being as inevitable as life and love and it makes the point that there’s nothing we can do to truly prepare for it. By allowing Emily to live, the film gives us a ray of hope that wasn’t present anywhere else in Our Town. The happy ending feels inauthentic. If Emily could live then why couldn’t Joe Crowell? For that matter, why did Emily’s younger brother have to die of a burst appendix on a camping trip?

But, other than the changed ending, Our Town is a pretty good adaptation of the stage play. While the film features an actual set (as opposed to the bare stage on which theatrical versions of Our Town are meant to be performed), director Sam Wood does a good job of retaining the play’s surreal, metatheatrical style. Making good use of shadow and darkness, Wood and cinematographer Bert Glennon made Grover’s Corner seem like a half-remembered memory or a fragment of a barely cohesive dream.

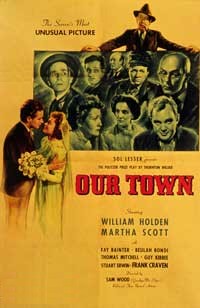

Frank Craven, who originated the role on Broadway, is properly dry as the Stage Manager and, in the role of Doc Gibbs, Thomas Mitchell is so sober and respectable that it’s hard to believe that, in just 6 years, the same actor would play the delightfully irresponsible Uncle Billy in It’s A Wonderful Life. Emily and George are played by Martha Scott and an impossibly young William Holden, both of whom give wonderfully appealing performances.

With the exception of that changed ending, Our Town is a worthy adaptation of a classic play. It was nominated for Best Picture but lost to another literary adaptation, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca.