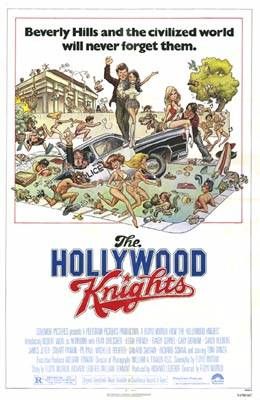

Halloween Night, 1965. While the high school holds a pep rally and the Beverly Hills Homeowners Association debate the best way to tackle the problem of juvenile delinquency, the Hollywood Knights hang out at Tubby’s Drive-In, their favorite burger joint. The Hollywood Knights are a car club and a group of fun-loving rebels, determined to have a good time and to always humiliate Officers Clark (Sandy Helberg) and Bimbeau (Gailard Sartain). In practice, this amounts to a lot of jokes about flatulence and Newcomb Turk (Robert Wuhl) mooning the cops every chance the he gets. I’m hoping a stunt butt was used for the mooning shots. If I had known watching Hollywood Knights would mean seeing Robert Wuhl’s bare ass a dozen times over 91 minutes, I wouldn’t have started the movie.

Halloween Night, 1965. While the high school holds a pep rally and the Beverly Hills Homeowners Association debate the best way to tackle the problem of juvenile delinquency, the Hollywood Knights hang out at Tubby’s Drive-In, their favorite burger joint. The Hollywood Knights are a car club and a group of fun-loving rebels, determined to have a good time and to always humiliate Officers Clark (Sandy Helberg) and Bimbeau (Gailard Sartain). In practice, this amounts to a lot of jokes about flatulence and Newcomb Turk (Robert Wuhl) mooning the cops every chance the he gets. I’m hoping a stunt butt was used for the mooning shots. If I had known watching Hollywood Knights would mean seeing Robert Wuhl’s bare ass a dozen times over 91 minutes, I wouldn’t have started the movie.

The humor is crude but the movie has a serious side, one that was cribbed from American Graffiti. Duke (Tony Danza), a senior member of the club, is upset that his girlfriend (Michelle Pfeiffer, in her film debut) is working as a car hop. He’s also sad that his buddy, Jimmy Shine (Gary Graham), is leaving in the morning for the Army. Jimmy’s not worried about being sent to Vietnam because Americans are only being sent over there as advisors. Hollywood Knights doesn’t end with a Graffiti-style epilogue but if it did, Jimmy would be the one who never came home. The serious scenes work better than the comedy, due to the performances of Gary Graham, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Tony Danza. I can’t believe I just said that either. Danza, though he’s way too old to be playing a high school student, is actually really good in this movie. Pfeiffer doesn’t get to do much but, from her first scene, it’s easy to see why she became a star. The camera loves her and she brings her character to life, despite not having much screen time.

Unfortunately, the drama takes a back seat to a lot of repetitive humor. The problem isn’t that the humor is crude. One thing that has always been true is that, regardless of the year, teenage boy humor is the crudest humor imaginable. Even back in prehistorical times, teenage boys were probably drawing dirty pictures on the walls of their caves. The problem is that the humor is boring and Robert Wuhl is even more miscast as a high school student as Tony Danza was. Fran Drescher plays a high school student with whom Turk tries to hook up. Drescher, like Pfeiffer, comes across as being a future star in the making. Robert Wuhl comes across as being the future creator of Arli$$.

The Hollywood Knights has a bittersweet ending, the type that says, “It’ll never be 1965 again.” This movie made me happy that it will never be 1965 again. 1965 should have sued The Hollywood Knights for slander. Hollywood Knights tried to mix the nostalgia of American Graffiti with the raunchiness of Animal House but it didn’t have the heart or creativity of either film. At least some of the member of the cast went onto better things.