I love movies and I love books so I guess it would stand to reason that I love books about movies the most of all. (I also love movies about books but there are far fewer of those, unfortunately.) Below are my personal favorites. I’m not necessarily saying that these are the ten greatest film books ever written. I’m just saying that they’re the ones that I’m always happy to know are waiting for me at home.

10) Soon To Be A Major Motion Picture by Theodore Gershuny — This is one of the great finds of mine my life. I found this in a used bookstore and I bought it mostly because it only cost a dollar. Only later did I discover that I had found one of the greatest nonfiction books about the shooting of a movie ever written! Gershuny was present during the filming of a movie called Rosebud in the early 70s. I’ve never seen Rosebud but, as Gershuny admits, it was a critical disaster that managed to lose a ton of money. The book provides a fascinating wealth of backstage gossip as well as memorable portraits of director Otto Preminger and actors Robert Mitchum (who was originally cast in the lead role), Peter O’Toole (who took over after Mitchum walked off the set), and Isabelle Huppert. If nothing else, this book should be read for the scene where O’Toole beats up critic Kenneth Tynan.

9) Suspects by David Thomson — A study of American cinema noir disguised as a novel, Suspects imagines what would happen if George Bailey from It’s a Wonderful Life fell in love with Laura from the movie of the same name. Well, apparently it would lead to Sunset Boulevard’s Norma Desmond having an affair with Chinatown’s Noah Cross and to one of George’s sons, sensitive little Travis, getting a job in New York City as a Taxi Driver. And that’s just a small sampling of what happens in this glorious mindfuck of a novel.

8 ) Profondo Argento by Alan Jones — Long-time fan Alan Jones examines each of Dario Argento’s films (even Argento’s obscure historical comedy The Five Days of Milan) and proceeds to celebrate and (in many cases) defend Argento’s career. Jones also interviews and profiles several of Argento’s most frequent collaborators — Daria Nicolodi, Asia and Fiore Argento, Simon Boswell, Claudio Simonetti, Keith Emerson, George Romero, Lamberto Bava, Michele Soavi, and many others. Jones’ sympathetic yet humorous profile of Luigi Cozzi is priceless.

7) Spaghetti Nightmares by Luca Palmerini — Spaghetti Nightmares is a collection of interviews conducted with such Italian filmmakers as Dario Argento, Ruggero Deodato, Umberto Lenzi, Lucio Fulci, and others. Among the non-Italians interviewed are Tom Savini (who, as always, comes across as appealingly unhinged) and David Warbeck. (Sadly, both Warbeck and Fulci would die shortly after being interviewed.) What makes this interesting is that, for once, Argento, Fulci, et al. are actually being interviewed by a fellow countryman as opposed to an American accompanied by a translator. As such, the subsequent interviews turn out to be some of the most revealing on record.

6) Sleazoid Express by Bill Landis and Michelle Clifford — Landis and Clifford’s book is both a history and a defense of the old grindhouse theaters of New York City. Along with describing, in loving and memorable detail, some of New York’s most infamous grindhouses, they also write about some of the more popular movies to play at each theater. Along the way, they also offer up revealing profiles of such legendary figures as David Hess and Mike and Roberta Findley. Reading this book truly made me mourn the fact that if I ever did find myself in New York City, I won’t be able to hit the old grindhouse circuit.

5) Beyond Terror: The Films of Lucio Fulci by Stephen Thrower — Fulci has always been a terribly underrated director and, indeed, it’s easy to understand because, in many ways, he made movies with the specific aim of alienating and outraging his audience. It requires a brave soul to take Fulci on his own terms and fortunately, Stephen Thrower appears to be one. Along with the expected chapters on Fulci’s Beyond Trilogy and on Zombi 2, Thrower also devotes a lot of space to Fulci’s lesser known works. Did you know, for instance, that before he became the godfather of gore, Fulci specialized in making comedies? Or that he also directed two very popular adaptations of White Fang? Thrower also examines Fulci’s often forgotten westerns as well as his postapocalyptic sci-fi films. And, best of all, Thrower offers up a defense of the infamous New York Ripper that, when I read it, actually forced me to consider that oft-maligned film in a new light. That said, Thrower does admit to being as confused by Manhattan Baby as everyone else.

4) Immoral Tales by Cathal Tohill and Pete Toombs — Tohill and Toombs offer an overview of European “shock” cinema and some of the genre’s better known masters. The book contains perhaps the best critical examination of the work of Jean Rollin ever written. The authors also examine the work of Jesus Franco and several others. This is a great book that reminds us that the Italians aren’t the only ones who can make a great exploitation film.

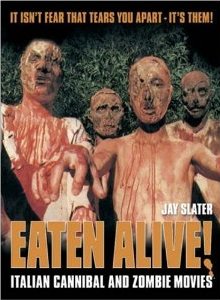

3) Eaten Alive by Jay Slater — This book offers an overview of the Italian film industry’s legendary cannibal and zombie boom. Along with reviewing every Italian movie to feature even the slightest hint of cannibalism or the living dead (this is one of the few books on Italian cinema that discusses both Pasolini and Lucio Fulci as equals), Eaten Alive also features some very revealing interviews with such iconic figures as Catriona MacColl, Ian McCullough, and especially Giovanni Lombardo Radice. Radice, in fact, also contributes a memorable “guest” review of one of the movies featured in the book. (“What a piece of shit!” the review begins.) Memorable reviews are also contributed by Troma film founder Lloyd Kaufman who brilliantly (and correctly) argues that Cannibal Holocaust is one of the greatest films ever made and Ramsey Campbell who hilariously destroys Umberto Lenzi’s infamous Nightmare City.

2) The Book of the Dead by Jamie Russell — If, like all good people, you love zombies then you simply must do whatever it takes to own a copy of this book. Starting with such early masterpieces as White Zombie and I Walked With A Zombie, Russell proceeds to cover every subsequent zombie film up through George Romero’s Land of the Dead. Russell offers up some of the best commentaries ever written on Romero’s Dead films, Fuci’s Beyond Trilogy, Rollin’s Living Dead Girl, and Spain’s Blind Dead films. The pièce de résistance, however, is an appendix where Russell describes and reviews literally ever zombie film ever made.

1) All The Colors Of the Dark by Tim Lucas — This is it. This is the Holy Grail of All Film Books. If you’ve ever asked yourself if any book is worth paying close to 300 dollars, now you have your answer. This one is. Tim Lucas offers up the most complete biography of director Mario Bava ever written. In fact, this may be the most complete biography of any director ever written! Lucas examines not only Bava’s life but also every single movie that Bava was ever in any way connected to, whether as a director or as a cameraman or as the guy in charge of the special effects. This is 1,128 pages all devoted to nothing but the movies. This is the type of book that makes me thankful to be alive and I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Tim Lucas for writing it.