It was in 1988 that one of the darkest, least-discussed episodes of World War II history was thrust into public consciousness through the work of Chinese filmmaker T.F. Mou. The film in question is Men Behind the Sun, an infamous fusion of historical drama and horror that still provokes debate nearly forty years later. Unlike traditional war films that depict heroic battles, military strategy, or patriotic sacrifice, this film ventures deep into the murky shadows of wartime atrocity, unearthing the story of Unit 731—a chapter that had remained largely buried outside of East Asia.

The film is set during Japan’s occupation of Manchuria, beginning in the 1930s and stretching into the final years of the Pacific War. Mou frames much of the story through the perspective of a group of young Japanese boys who have been conscripted into service with the Imperial Army. These youths, filled with notions of loyalty and honor, find themselves assigned to Unit 731, a supposedly scientific research group whose true mission soon becomes horrifyingly clear. What they encounter—and what the audience is forced to witness—exposes both the capacity for cruelty and the terrifying ease with which human beings can normalize horror under the authority of war.

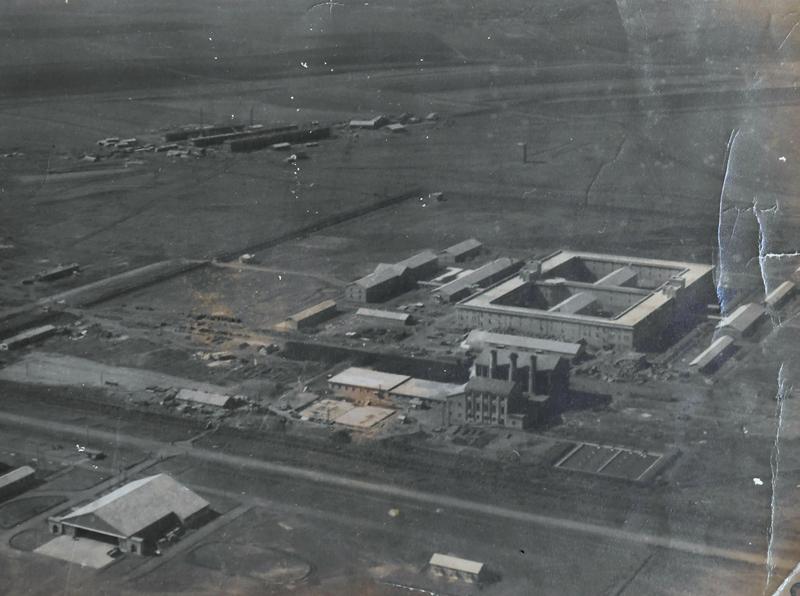

Unit 731 was not a fictional invention, but a very real military research facility overseen by General Shirō Ishii, a figure who still looms as one of World War II’s most notorious war criminals. Under the guise of developing defenses against epidemics and advancing medical knowledge, Ishii ran a program devoted to biological and chemical warfare research. The methods employed were monstrous: prisoners were intentionally infected with plague and anthrax, subjected to vivisections while still alive, had organs harvested for study, and were sealed within hypobaric chambers to measure the effects of barometric pressure. Others were exposed to grenades, chemical agents, or lethal extremes of cold and heat. The victims—callously referred to by their tormentors as “logs”—were largely drawn from the local Chinese population, though Russians, Koreans, and even children and pregnant women were subjected to the same fate. Official records suggest there were no survivors of these experiments.

In the film, the reaction of the Youth Corps to these atrocities provides the closest thing to a moral anchor. Initially repulsed, the boys attempt to adhere to the strict code of loyalty and duty impressed upon them by the Imperial Army. They are torn between horror at what they observe and fear of disobedience. But when a young Chinese boy whom they had befriended is selected as one of Unit 731’s subjects, the mask of discipline begins to crumble. Their attempt at resistance becomes both a moral turning point and a tragic acknowledgment of the futility of challenging the machinery of the Japanese war state.

What makes Men Behind the Sun stand out is its fragmented, almost documentary-like structure. Rather than weaving a straightforward dramatic narrative, Mou constructs the film as a series of stark vignettes, each showcasing one monstrous experiment after another. This disjointed quality mirrors the cold and methodical way Unit 731 carried out its work, giving the audience little comfort or space to detach. While the special effects often carry the look of late-1980s low-budget filmmaking, they remain powerfully effective in provoking revulsion. Time has not dulled their impact: the crude visual horror still conveys the visceral reality of suffering more effectively than polished stylization ever could.

To some, the film crosses too far into exploitation, presenting misery in a way that risks sensationalism. To others, it serves as a vital cultural reckoning, a way of exposing truths that were long suppressed not just in Japan but internationally. Men Behind the Sun may not offer the catharsis of traditional war cinema, but its unflinching confrontation with atrocity ensures it occupies a singular place in film history. Even more unsettling is the knowledge that outside the world of film, General Shirō Ishii himself escaped accountability. After Japan’s surrender, he cooperated with U.S. military authorities, trading his research findings for immunity from prosecution. As the Cold War escalated, his expertise in biological and chemical warfare was deemed too valuable to dismiss, and so the crimes of Unit 731 were quietly buried in exchange for data. This chilling epilogue—rooted not in cinema but in historical fact—ensures that the horror of Men Behind the Sun lingers long after the credits roll.