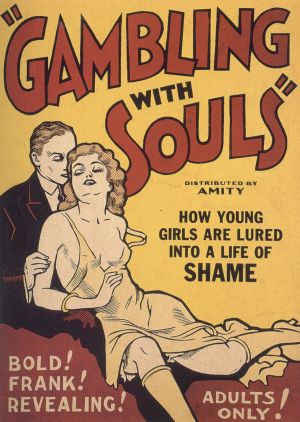

The 1948 film Good Time Girl is currently available on Netflix and I have to admit that, based on the name alone, I was expecting it to be another somewhat campy exploitation film about juvenile delinquency, something along the lines of Damaged Lives and Gambling With Souls.

And that’s certainly how the film began. A troubled teenager named Lyla (Diana Dors) has been arrested and is sent to the juvenile court where the concerned Miss Thorpe (Flora Robson) tells Lyla that if she doesn’t change her ways, she could end up just like Gwen Rawlings. Who is Gwen Rawlings? That’s what we spend the rest of this short film finding out.

The film shows how Gwen (Jean Kent) was raised in an abusive household and how, at the age of 16, she ran way from home. The first person she met was the handsome and charming Jimmy (Peter Glenville) who turns out to be a low-level gangster. (His pinstrip suit and mustache give him away.) Jimmy gets Gwen a job as a hat-check girl at a club run by the enigmatic Maxey (Herbert Lom). Gwen meets and falls in love with a musician named Red (Dennis Price) but Red explains that he’s not only too old for her but he’s married as well. Soon, Gwen is living with Jimmy and Jimmy is regularly abusing her. When Maxey sees that Jimmy has given her a black eye, he has Jimmy beaten up and fired. Jimmy responds by slashing Maxey’s face and then framing Gwen for jewelry theft.

Gwen is sent to reform school, where she falls under the influence of the somewhat demonic Roberta (played, in a genuinely menacing performance, by Daniel Day-Lewis’s mother, Jill Balcon). Reform school only succeeds in making Gwen tougher and angrier. When a mini-riot breaks out in the cafeteria, Gwen takes advantage of the confusion and escapes.

Back on the streets and with the police searching for her, Gwen falls in with a succession of different criminals. When she meets two military deserters, it leads to the type of tragedy that could just as easily befall Lyla if Lyla doesn’t change her ways.

This is one of those films where the worst possible thing that could happen always happens and, as a result, it’s all rather melodramatic. But, as opposed to a film like Reefer Madness or Sex Madness, it never gets so melodramatic that it becomes implausible. Instead, it’s actually a very watchable portrait of people living on the margins of acceptable society. Director David MacDonald fills the screen with menacing images and the pace never lags. The film is also full of great performances from character actors that you’ll probably recognize from countless Hammer horror films. Herbert Lom is especially impressive as the quietly intimidating Maxey.

I wasn’t expecting much from Good Time Girl but it’s definitely worth watching.