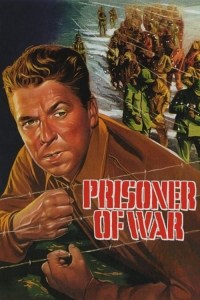

The setting is the Korean War. After getting information that American POWs are being tortured and brainwashed in North Korean prisoner-of-war camps, Major Hale (Harry Morgan) assigns Webb Sloane (Ronald Reagan) to go undercover. After parachuting behind enemy lines, Webb spots a group of POWs being marched through the snow and joins the group. From the minute that Webb joins the march, he begins to observe war crimes. The death march itself, with the POWs being forced to move in freezing weather, is itself a war crime. At the POW camp, Webb discovers the presence of an arrogant Soviet interrogator (Oscar Homolka) and a routine designed to break the POWs down until their ready to betray their native country. Some POWS, like Captain Stanton (Steve Forrest), refuse to break. Others, like cowardly Jesse Treadman (Dewey Martin), break all too quickly. Webb sends the information back to Hale and eventually tries to make his escape.

The setting is the Korean War. After getting information that American POWs are being tortured and brainwashed in North Korean prisoner-of-war camps, Major Hale (Harry Morgan) assigns Webb Sloane (Ronald Reagan) to go undercover. After parachuting behind enemy lines, Webb spots a group of POWs being marched through the snow and joins the group. From the minute that Webb joins the march, he begins to observe war crimes. The death march itself, with the POWs being forced to move in freezing weather, is itself a war crime. At the POW camp, Webb discovers the presence of an arrogant Soviet interrogator (Oscar Homolka) and a routine designed to break the POWs down until their ready to betray their native country. Some POWS, like Captain Stanton (Steve Forrest), refuse to break. Others, like cowardly Jesse Treadman (Dewey Martin), break all too quickly. Webb sends the information back to Hale and eventually tries to make his escape.

It’s not terrible. That the North Koreans and, later, the North Vietnamese tortured their POWs and forced some of them to denounce America is a matter of the historical record and, for a 1954 film, Prisoner of War doesn’t shy away from the brutality of the torture that POWs were often subjected too. Of all of Reagan’s film, Prisoner of War had the strongest anti-communist message, though Reagan himself feels miscast as a hard-boiled secret agent. (Reagan’s affability comes through even in a film set in a POW camp.) Sending someone undercover into a prisoner of war camp and then hoping that they’ll find a way to escape doesn’t sound like the most efficient way to determine if the Geneva Convention is being violated.

The film features a dog who is found by one of the POWs. Don’t get attached.