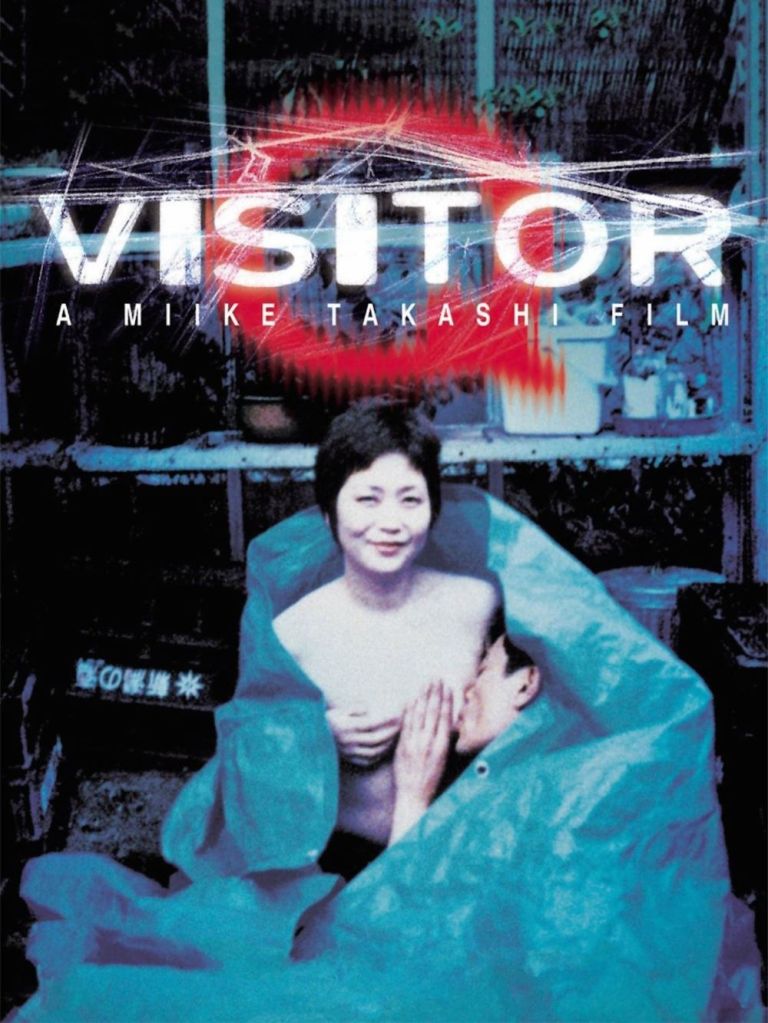

Miike Takashi’s 2001 film Visitor Q (called Bizita Q in Japan) is definitely one of the most bizarre and disturbing movies out there. It often gets compared to the work of Quentin Tarantino, but that comparison really doesn’t do Miike justice. Tarantino’s style is all about showing violence in a flashy, stylized way that sometimes feels more like entertainment or homage than outright shock. Miike, on the other hand, takes a very different approach—his films are much more raw, unfiltered, and transgressive. Where Tarantino’s violence can almost feel like a performance, Miike’s hits you in a way that’s meant to provoke and unsettle on a deeper level.

Visitor Q is a wild, surreal ride that dives headfirst into the messy mix of violence and sex that’s so common in today’s media, with a cheeky nod toward reality TV culture. The film came out of Japan at a really interesting time, when the culture was pretty conflicted about Western influences. Japan often points fingers at the West for “decadence” and moral decline, but at the same time, it produces some of the most intense and boundary-pushing entertainment around—like anime and manga filled with everything from weirdly sexualized creatures (yes, tentacles, lots of tentacles) to ultra-violent stories that Western media would blush at.

The plot itself is maybe the simplest part of the whole thing. It’s about a down-on-his-luck former TV reporter named Q Takahashi who’s trying to support his dysfunctional family by filming a documentary about how violence and sex in media affects young people today. From there, the story quickly spins into something much darker and more uncomfortable, focusing on his family’s raw problems: drug abuse, emotional numbness, incest, necrophilia, and other twisted stuff that’s hard to even put into words.

What really makes Visitor Q stand out is how Miike doesn’t hold anything back. This film isn’t trying to make you comfortable or distract you with flashy effects. Instead, it confronts you with some very real, very uncomfortable issues. Miike has a fearless way of showing violence and sex that feels totally unfiltered and even brutal, forcing you to face parts of human nature and society that most movies would shy away from or sugarcoat.

It’s easy to see how this movie channels the spirit of the Marquis de Sade, that infamous figure known for embracing taboo and shock to criticize societal hypocrisy. Miike takes this spirit and uses it to spotlight the way media—and especially the voyeuristic culture of reality TV—turns personal pain and dysfunction into public spectacle. The movie asks us to think about how watching violence and sex over and over might warp not just society’s values, but how people actually relate to one another.

One thing Visitor Q pokes at pretty hard is voyeurism, the idea of watching other people’s lives like it’s entertainment. The former TV reporter filming his family for the documentary is both an observer and a participant, and the film forces viewers to question the ethics of watching intimate, often tragic moments unfold just for the sake of entertainment. It’s a powerful reminder of what media voyeurism can do to real lives.

Another theme that hits home is how desensitized people have become to violence and sex. The family in the movie often reacts to brutal, horrible things with complete indifference—almost like they’re numb from being exposed to this stuff all the time. Miike seems to be saying that when we see violence and sex as everyday entertainment, it dulls our emotions and disconnects us from the human suffering behind those images. This is especially relevant for young people growing up in a media-saturated world, which is exactly what the film’s documentary narrator is trying to get at.

Some of the film’s more extreme themes, like incest and necrophilia, are obviously shocking, but Miike uses them to highlight just how broken the family is. These aren’t just there for shock value—they’re symbols of how far relationships can fall apart when love, respect, and communication break down entirely. The film uses these taboos as metaphors for emotional neglect and societal decay, asking us to look hard at the dark corners of family life and human nature that most media avoids.

Watching Visitor Q is definitely not an easy ride. At first, most people find themselves looking away or flinching because the content is so wild and graphic. But it’s interesting how, over time, viewers start watching the movie without turning away, even if what they see is still deeply disturbing. The film somehow pulls you in with its surreal style and brutal honesty, making you confront just how far you’re willing to go in understanding these messed-up family dynamics and cultural critiques.

Stylistically, the film bounces between stark realism and surreal, almost absurd imagery. This gives it a rollercoaster tone that keeps you off balance—one moment it’s brutally raw, the next it’s almost darkly comedic or bizarre. This mix mirrors the instability of the family and the unpredictable nature of their world. Miike really embraces both the artistic and the extreme exploitation sides of filmmaking here, unapologetically pushing boundaries with each scene.

Despite all the shocking stuff, the film comes with a clear message about the relationship between media, sex, and violence. It’s not just reflecting society’s problems; it’s suggesting that media actually shapes how we think, feel, and behave—especially for kids. The film also takes a swipe at reality TV, highlighting how people get a twisted sense of pleasure from watching others’ suffering and humiliation. This is even more relevant today with social media and constant livestreams making all aspects of life a public show.

Miike’s gritty and unfiltered take makes it clear he isn’t just copying Western transgressive directors—he’s got his own voice and style that’s as challenging as it is unique. Where Tarantino’s films entertain and provoke with wit and style, Miike’s work disturbs and pushes, asking viewers to get uncomfortable and reflect. Comparisons to Pasolini, the Italian filmmaker known for his raw and provocative films, fit well here. Like Pasolini, Miike straddles the line between art and exploitation, using shock to force deeper questions about society.

In the end, Visitor Q isn’t a movie for casual watching or easy enjoyment. It’s intense, often repugnant, and demands a tough kind of attention. But for those willing to dive into its messy, surreal, and disturbing world, it offers a powerful look at how media influences family, society, and morality. Miike Takashi is definitely not Japan’s Tarantino—he’s a far more transgressive filmmaker who dares to challenge audiences by taking them into the most uncomfortable and raw parts of human experience. If one has the courage and curiosity, Visitor Q is an unforgettable, provocative film that forces us to think hard about voyeurism, media excess, and just how dark and strange life can get behind closed doors.