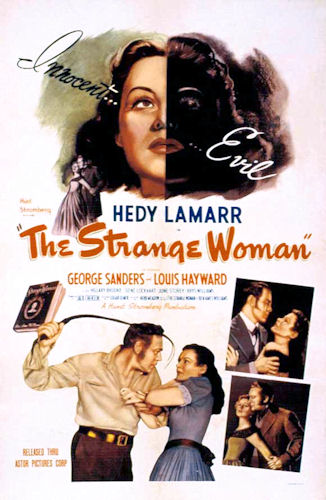

The eleventh film in Mill Creek’s Fabulous Forties box set was 1946’s The Strange Woman. The Strange Woman is one of those film noir/small town melodrama hybrids that seem to have been something of a cinematic mainstay in the mid to late 40s.

The Strange Woman of the title is Jenny Hager (Hedy Lamarr) and she’s not just strange because she’s got an Eastern European accent despite having grown up in Bangor, Maine. The film opens in 1824 and we watch as tween Jenny pushes one her classmates into a river, despite the fact that he can’t swim. At first, she seems content to let him drown. However, once she realizes that an adult is watching, Jenny jumps into the river and saves his life.

Ten years later, Jenny has grown up to be the most beautiful woman in Maine. However, her father is abusive and regularly whips her as punishment for being too flirtatious. Jenny has plans, though. She wants to marry the richest man in town, a store owner and civic leader named Isaiah Poster (Gene Lockahrt). Isaiah also happens to be the father of Ephraim (Louis Hayward), the young man who Jenny tried to drown at the beginning of the film.

And eventually, Jenny’s dream does come true. She marries Isaiah, even though she doesn’t love him. She just wants his money and is frustrated when the sickly Isaiah keeps recovering from his frequent illnesses. She starts to flirt with the weak-willed Ephraim, trying to manipulate him into killing his father.

Of course, even as she’s manipulating Ephraim, she’s also flirting with John Everd (George Sanders), despite the fact that John is already engaged to the daughter of the local judge. Though Everd is a good and decent guy, he still finds himself tempted by Jenny.

What makes all of this interesting is that Jenny isn’t just a heartless femme fatale. Throughout the film, there are several instances when she wants to do good but can’t overcome her essentially heartless nature. She gives money to charity and, whenever she listens to one of the local fire-and-brimstone preachers, she finds herself tempted to give up her manipulative ways.

The Strange Woman was directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, who is probably best known for directing the ultimate indie film noir, Detour. He was a childhood friend of Hedy Lamarr’s and she specifically asked that he direct her in The Strange Woman. As a result, this film represents one of the few times that Ulmer was given a budget that was equal to his talents. What makes The Strange Woman stand out from other 40s melodramas — like Guest In The House, for example — is that, even with the larger budget, Ulmer’s direction retains the same deep cynicism and dream-like intensity that distinguished his work in Detour. The film remains sympathetic to Jenny, even as she often suffers the punishments that were demanded by the production code.

In the role of Jenny , Hedy Lamarr is a force of a nature. She is so intense and determined that watching her as Jenny is a bit like seeing what Gone With The Wind would have been like if Scarlet O’Hara had been a total sociopath. Even the fact that Lamarr’s accent is definitely not a Maine accent seems appropriate. It sets Jenny apart from the boring people around her.

It reminds us that, even if she is “strange,” there is no one else like Jenny Hager.