Though the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences claim that the Oscars honor the best of the year, we all know that there are always worthy films and performances that end up getting overlooked. Sometimes, it’s because the competition too fierce. Sometimes, it’s because the film itself was too controversial. Often, it’s just a case of a film’s quality not being fully recognized until years after its initial released. This series of reviews takes a look at the films and performances that should have been nominated but were,for whatever reason, overlooked. These are the Unnominated.

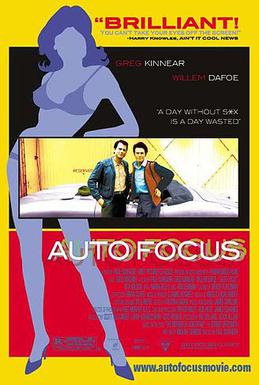

The 2002 film Auto Focus start out as almost breezy satire of the perfect all-American life and it ends with an act of shocking violence. It’s based on a real-life mystery, a murder that revealed a secret life.

When we first see Bob Crane (Greg Kinnear), he’s a disc jockey and a drummer living in the suburbs of Los Angeles in the mid-60s. He’s got what would appear to be the ideal life. He’s got a nice house. He and his wife (Rita Wilson) seem to be devoted to each other. His children are adorable. He goes to church. He tells corny Dad jokes. He’s got a quick smile and a friendly manner and it’s impossible not to like him. When he gets offered the lead in a sitcom, his happiness and enthusiasm feels so generous that it’s impossible not to be happy for him.

Of course, the show is a comedy that takes place in World War II POW camp, which doesn’t really sound like a surefire hit or really anything that should be put on the air. (“Funny Nazis?” Crane says in disbelief when he’s first told about the project.) Still, with Crane in the lead role, Hogan’s Heroes becomes a hit and, for a while, Bob Crane becomes a star and it seems like it couldn’t have happened to a more deserving guy.

The problem, of course, is that Crane seems like he’s too good to be true and we all know what they say about things like that. From the start, there are hints that Crane may be hiding another side of his personality. His wife, for instance, is not happy when she discovers his stash of pornographic magazines in their garage. (“They’re photography magazines!” Crane protests with a smile that’s a bit too quick.) Crane obviously enjoys the recognition that comes from being the star of a top-rated show. He starts hanging out at strip clubs, occasionally playing drums with the club’s band and watching the dancers with a leer that’s really not all that different from the smile that he flashes whenever he asks anyone if they want an autograph.

Crane also meets John Carpenter (Willem DaFoe), an electronics expert who introduces him to the then-expensive and exclusive world of home video. As opposed to the clean-cut and smoothly-spoken Crane, Carpenter is so awkward that it’s sometimes painful to watch him move or listen to him speak. He’s the epitome of the Hollywood hanger-on, the type who has deluded himself into thinking that his celebrity clients genuinely like him and enjoy his company. He and Crane become fast friends, though it’s always obvious that Crane considers himself to be better than Carpenter. However, Carpenter is the only person with whom Crane can share the details of his secret life.

The film covers several years, from the late 60s to the mid-70s. Crane goes from being so clean-cut that he neither drinks nor curses to being so addicted to sex that he can stop himself even when it starts to destroy his career and leads to him losing everything that he loves. Carpenter and Crane’s friendship becomes progressively more and more self-destructive until the film ends in violence and tragedy.

Auto Focus begins on a light and breezy note but, as Crane’s addiction grows, the film grows darker. By the time the movie enters the 70s, the camerawork becomes more jittery and the once soft-spoken Crane seems to be drowning in his own anxiety. He becomes the type who causally goes from talking to Carpenter about how he wants to direct the world’s greatest sex film to cheerfully announcing that Disney has decided to cast him in a film called SuperDad. Auto Focus‘s key scene comes towards the end, when Crane is a guest on a silly cooking show and shocks the audience by harassing a woman sitting in the front row. When the audience boos, Crane flashes his familiar smile and it becomes obvious just how much of Crane’s life has been spent hiding behind that smile. By the end of the film, not even Crane himself can keep track of whether or not he’s a wholesome comedy star or a self-destructive sex addict.

Both Greg Kinnear and Willem DaFoe gave Oscar-worthy performance in Auto Focus, performances that hold your interest even after their characters sink to some truly low depths. The film makes good use of Kinnear’s amiable screen presence and Kinnear convincingly creates a man who wishes that he could be the person that he’s fooled everyone into thinking that he is. By the time he’s reduced to begging his agent (well-played by Ron Leibman) to find him a game show so that he can finally stop doing dinner theater, it’s hard not to have a little sympathy for him, even if the majority of his problems are self-created. As Carpenter, DaFoe is convincingly creepy but, at times, he’s also so pathetic that, again, you can’t help but feel a little sorry for him. At his worst, Carpenter is the 70s equivalent of the twitter user who stans a celebrity by sending them adoring tweets and then picking fights with anyone who disagrees.

Unfortunately, the Academy nominated neither Kinnear for Best Actor nor DaFoe for Best Supporting Actor. The competition for Best Actor was fierce that year, with Nicolas Cage, Michael Caine, Daniel Day-Lewis, and Jack Nicholson all losing to Adrien Brody in The Pianist. While Kinnear deserved a nomination, it’s hard to say who I would drop from that line-up to make room for him. As for DaFoe, I would argue that he was more deserving of a supporting actor nomination than The Hours‘s Ed Harris or The Road To Perdition’s Paul Newman. Perhaps DaFoe was just too convincing as the type of clingy groupie that most members of the Academy probably dread having to deal with.

Nominated or not, Auto Focus is a disturbing and ultimately sad look at the darkness that often hides behind a perfect facade.