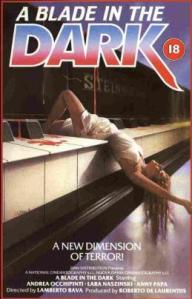

First released in 1983, Conquest takes place in a mystical land, one where humans, dolphins, and sheep live alongside witches, werewolves, and zombies. It’s a place of magic, evil, and multiple decapitations. As the film begins, a young man named Ilias (played by Andrea Occhipanti, who also appeared in Lucio Fulci’s The New York Ripper) has just turned 18 and is heading out on his first quest. His father gives him a magic bow, which shoots laser-like arrows. Illias boards a raft and sails off to do whatever people do on quests. To be honest, it’s always strange to me that people in films like this always want to go on quests. I mean, it never turns out well.

Ilias finds himself in a land that is ruled by Ocron (Sabrina Sian), a naked witch who spends her time fondling a snake and snorting what appears to be cocaine. During one of her drug binges, Ocron has a vision of a faceless man who carries a magic bow. She realizes that the man could potentially destroy her and end her reign of evil. She orders her werewolf soldiers to take a break from their usual routine of killing cave people so that they can scour the land and destroy the man with the bow.

Fortunately, Ilias has made a new friend! Mace (Jorge Rivero) is a wandering outlaw who claims that he doesn’t care about anyone but who takes an instant liking to Ilias. Soon, Mace and Ilias are inseparable as they walk through the countryside together, stopping only to kill a hunter and steal his food …. wait, that doesn’t sound very heroic. Mace’s argument is that hunters themselves are not heroic but still, it really does seem more like cold-blooded murder than anything else. It’s a weird scene but, then again, this Italian film is a weird movie.

Eventually, Ilias decides that his destiny is to destroy Orcan. Though Mace doesn’t think that it’s a good idea to cross the most powerful witch in this strange world, he does agree to escort Ilias to the seashore. (One gets the feeling that if Conquest had been released more recently, as opposed to 1983, Ilias and Mace would have launched a thousand ships.) But things get complicated on the way, with both Ilias and Mace going through several different changes of heart. Of course, they also run into zombies, underground monsters, and super-intelligent dolphins….

Conquest was directed by Lucio Fulci, the Italian filmmaker who was responsible for some of the most visually striking and narratively incoherent horror films ever made. With Zombi 2, Fulci launched the Italian zombie boom. With The Beyond trilogy, Fulci directed three of the most intriguingly surreal horror films ever made. With The New York Ripper and Don’t Torture A Duckling, Fulci took the giallo genre to its logical and most disturbing conclusion. Fulci made blood-filled films, ones in which the overall plot was never as important as the set pieces. That’s certainly the case of Conquest, which pays homage to the old sword-and-sorcery films while also including zombies and a few rather graphic torture scenes. (The scene in which one person is literally split in half is shocking, even by the standards of Fulci.) And yet there’s an odd earnestness to Conquest, as both Ilias and eventually Mace are horrified by Ocran’s cruelty and willing to risk their lives to put an end to it. The friendship between Ilias and Mace comes out of nowhere but the film takes it seriously and, as a result, the final scenes are far more emotional than you might expect from a director of Fulci’s reputation. It’s tempting to consider Conquest as a bit of a prequel to The Beyond trilogy. Perhaps we’re looking into the Beyond itself and discovering that, even in that disturbing world, there are people who are willing to risk their lives to battle evil.

Conquest was not one Fulci’s box office successes, which is a bit of a shame as it really does seem to be a film that he put his heart into. Unfortunately, Conquest was followed by the controversy surrounding The New York Ripper and the critical failure of Manhattan Baby. Fulci’s career went into decline and he soon found himself directing stuff like Aenigma. It’s a shame but I think many of Fulci’s so-called failures are ready to be rediscovered and reappraised. That’s certainly the case with Conquest.