The year is 1972 and the news is grim. The fighting continues in Vietnam. The protests continue at home. Crime is rising. The economy is struggling. Groups like the Weathermen and the SLA are talking about taking the revolution to the streets. In New York, the notorious murderers Krug Stillo (David Hess) and Fred “Weasel” Podowksi (Fred Lincoln) have broken out of prison and are one the run. They are believed to be traveling with Krug’s drug-addicted son, Junior (Marc Sheffler), and a woman named Sadie (Jeramie Rain), who is said to be feral and bloodthirsty.

However, Mari Collingwood (Sandra Cassel) doesn’t care about any of that. She’s just turned seventeen and she can’t wait to go to her first concert with her best friend, Phyllis (Lucy Grantham). Mari is naive, optimistic, and comes from from a comfortably middle-class family. Phyllis is a bit more worldly and tougher. As she explains it, her family works in “iron and steel.” “My mother irons, my father steals.”

While Mari’s parents (Richard Towers and Eleanor Shaw, though they were credited as Gaylord St. James and Cynthia Carr) bake a cake and prepare for Mari’s birthday party, Mari heads into the city with Phyllis. Before they go to the concert, they want to buy some weed. When they see Junior Stillo hanging out on a street corner, they assume he must be a dealer and they approach him. Junior takes them to an apartment, where they are grabbed by Weasel and Krug.

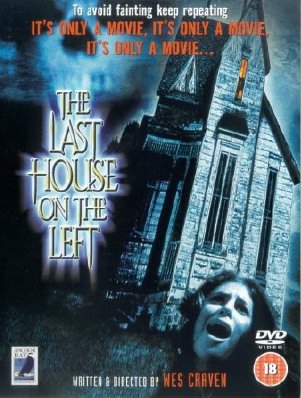

1972’s The Last House On The Left was advertised with the classic (and much-repeated line), “To avoid fainting, keep repeating, ‘It’s only a movie …. it’s only a movie…. it’s only a movie….” That advice is easy to remember during the first part of the film because, up until Mari and Phyllis approach Junior, the movie is fairly cartoonish, with Richard Towers giving an incredibly bad performance as Mari’s father. This film was Wes Craven’s debut as both a director and a writer. By his own admission, Craven had no idea what teenage girls would talk about and, as such, he just wrote a lot of dialogue in which Mari talked about her breasts and Mari’s mother complaining that young women no longer wore bras. (On the commentary that he recorded for the film’s DVD release, Craven succinctly explained, “I guess I was obsessed with breasts.”) This part of the film plays out like a weird counter-culture comedy. Even when we first meet Krug, he’s using his cigar to pop a little kid’s balloon.

The tone of the film jarringly shifts the minute that Mari and Phyllis step into that apartment. That’s largely due to the performances of David Hess and Fred Lincoln, who are both so convincing in their roles that it can be difficult to watch them. In real life, Fred Lincoln was a stuntman (he’s in The French Connection) and an adult film actor. David Hess, meanwhile, was a songwriter who was looking to break into acting. (Hess’s songs — some of which are beautifully sad and some of which are disturbingly jaunty — are heard throughout the movie.) Hess, in particular, is so frightening as Krug that he spent the rest of his career typecast as sociopathic murderers. The middle part of the film alternates between disturbingly realistic scenes of Mari and Phyllis being tortured and humiliated and cartoonish scenes involving two incompetent cops (one whom is played by Martin Kove) and Mari’s parents. Phyllis is murdered and dismembered in a graveyard and the gore effects remains disturbingly realistic even when seen today. Mari, after being raped by Krug, recites a prayer, and then wades into a nearby lake. Krug shoots her three times. Afterwards, Krug, Weasel, and Sadie try to wash the blood off of themselves, the expression on their faces indicating that even they understand that they’ve gone too far.

Eventually, Krug, Weasel, Sadie, and Junior stop off at a nearby house, claiming to be salespeople who just had a little car trouble. What they don’t realize is that the people who are generously welcoming them to spend the night are also the parents of Mari Collingwood….

Basing his script on Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, Wes Craven has often said that The Last House On The Left was meant to be a commentary on the Vietnam War and the way that other films had glamourized violence. That may or may not be true. (Craven has also said that, at the time, he was so desperate to direct a movie that he would have filmed almost anything.) What is true is that the violence in Last House On The Left is not easy to watch. Once it starts, it’s relentless and, at no point, is the audience given an escape. David Hess is so committed to playing a sadist that he never takes a moment to wink at the audience and say, “Hey, we’re just playacting here!” Craven shot the film in a guerilla style and the shaky camera, the natural light, and the grainy images leave you feeling as if you’re watching some sicko’s home movies. At the end of the movie, when Mari’s parents take the same joy in attacking her killers as Krug took in attacking their daughter, it’s hard not to feel that Mari has been forgotten. Everyone has been consumed by the violence that has erupted around them. Even though Richard Towers’s nearly blows the ending with a few hammy line readings, the film still leaves you exhausted.

Not surprisingly, The Last House On The Left was attacked by most reviewers when it was originally released. The movie played the drive-in and grindhouse circuit for three years, with producer Sean Cunningham often taking out advertisements in local newspapers that read: “You will hate the people who perpetrate these outrages—and you should! But if a movie—and it is only a movie—can arouse you to such extreme emotion then the film director has succeeded … The movie makes a plea for an end to all the senseless violence and inhuman cruelty that has become so much a part of the times in which we live.” The film’s advertisements also contained a warning that no one under 30 should see the movie. Needless to say, The Last House On The Left was a huge hit, especially with viewers under 30.

(One of the great ironies of film criticism is that one of the few critics to defend Last House On The Left was Roger Ebert. Ebert, who would later be one of the slasher genre’s biggest attackers, gave Last House On The Left a very complimentary review and praised it for its political subtext.)

Seen today, The Last House On The Left still packs a punch. It’s a shocking and shamelessly sordid film, one that shows hints of the talent that would make Wes Craven one of the most important directors to work in the horror genre. It’s flawed, it’s exploitive, it’s thoroughly unpleasant, and yet it’s also a film that sticks with you. It’s powerful almost despite itself. It’s not a movie that I would necessarily chose to watch on a regular basis but, at the same time, I can recognize it as being a historically important film. For better or worse, much of modern American horror owes a debt to Wes Craven’s Last House On The Left. Even today, when one is regularly bombarded with horrific images, Last House On The Left still has the power to shock.