Well, here we are at the end of both March and the 18 days of paranoia. We started things off with a review of The Flight That Disappeared and now, we end things with a look at the 1954 BBC production of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

“Orewllian” is a term that gets tossed around a lot nowadays, largely by people who the real George Orwell probably would have viewed rather dismissively. Ever since the election of Donald Trump, for instance, it’s become rather common for certain people of twitter to say that “Orwell was right” or that we’re living in an “Orwellian nightmare.” I remember after Trump’s press secretary blatantly lied about the size of the crowd at the inauguration, there was even a commercial that featured Zachary Quinto giving a hilariously overwrought reading of the final passage of George Orwell’s 1984. “He …. LOVED …. BIG …. BROTHER!” Quinto declared while staring grimly at the camera.

Interestingly enough, many of the same people who complain about Trump’s lies being Orwellian never used the term during the previous 8 years, when we were being constantly told that a permanent recession was actually a sign of a strong economy and that if people liked their doctor, they could keep them. The fact of the matter is that, for a lot of people, “Orwellian” is just a term that they use whenever a politician from the other side does something that they dislike. It makes you wonder how many of them have actually read 1984 because, if they had, they would surely know that — if we truly were living in the world depicted in Orwell’s novel — no one would be allowed to acknowledge it and, in fact, Orwell and his books would have vanished down the memory hole. Just the act of saying that we’re living in 1984 without getting sent to a reeducation camp is proof that we’re not (or, at least, we’re not just yet).

That’s not to say that 1984 isn’t an important work of literature. In fact, it’s probably one of the most important books ever written, which is why it does it such a disservice to glibly toss around the term Orwellian. Even if we aren’t living in Orwell’s world right now, it’s probably easier than ever to imagine a scenario where we eventually could. The Coronavirus pandemic, for example, is just the sort of thing that could lead to the people accepting the idea that the government is meant to be a Big Brother and that those who disagree deserve to be reported for the good of the people. It’s easy to imagine a future where people believe that history started with the Coranavirus and that everything that happened before the pandemic was just a hazy rumor, like Europe before the Renaissance. As such, even if the term Orwellian is overused, 1984 is still a book that needs to be read and understood.

There have been several film adaptations of 1984, some of which are better than others. My personal favorite is the 1985 film, which was directed by Michael Radford and which starred John Hurt and Richard Burton. Running a close second, however, would be the version that was made for the BBC in 1954.

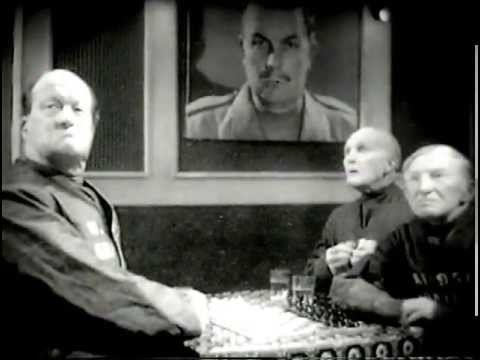

This version sticks closely to Orwell’s novel, though it downplays the book’s sexual themes. (This is not surprising considering that this version was made for 1950s television.) Though it condensed Orwell’s story, it hits all of the important points. Winston Smith (Peter Cushing) is a member of the Outer Party who works at the Ministry of Truth and who lives a rather drab existence in London, “the chief city of Airstrip One.” He is a citizen of Oceania, which has always been at war with Eurasia. Winston lives under a system of government called Ingsoc and every day, he spends two minutes hating a mysterious figure named Goldstein. All around him are posters of Big Brother, watching him and judging.

On the outside, Winston is a loyal party man but on the inside, he has questions and doubts. How can he not when he works for the Ministry of Truth? His job is to change history to reflect whatever the current version of it may be. Some of his co-workers, like Symes (Donald Pleaseance), are openly cynical about what they do. Others, like O’Brien (an imposing Andre Morell), seem as if they might be sympathetic to Winston’s doubts but Winston cannot be sure. Meanwhile, Winston has found himself obsessed with Julia (Yvonne Mitchell), who is a member of the Anti-Sex League but who might have doubts of her own. (Then again, she could also be a member of the Thought Police.)

When Winston is finally arrested for being a thoughtcriminal, it leads to a harrowing interrogation where he learns that truth doesn’t matter, the numbers add up to whatever the party says that they add up to, and that no one is strong enough to survive the ordeal of Room 101.

The BBC adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four was, for the most part, a live performance with a few filmed scenes inserted into the action. Still, the fact that the majority of the actors were delivering their lines lives brings a certain immediacy to the film. Everyone seem nervous and edgy. In real life, that could have been due to the fear that they would miss a line but it also feels appropriate for people who spend every day of their life being watched and judged by Big Brother. The entire production does an excellent job of creating a world where every minute is suffused in an atmosphere of dread and fear. From the minute we first see him, Winston seems to know that he’s doomed. The fact that Big Brother would rather torture and brainwash him rather than just make him disappear just makes things worse.

The production is full of actors — like Cushing, Morrell, and Pleasence — who would go on to become leading figures in the British horror industry and all of them do an excellent job bringing Orwell’s horror to life. Peter Cushing, with his mix of intelligent features and neurotic screen presence, makes for the perfect Winston Smith and Andre Morrell is just as perfectly cast as the fearsome O’Brien. The scene in which Winston is forced to confront Room 101 is still a harrowing one and this film perfectly nails the novel’s famous ending, doing so in a low-key manner that’s far more effective than the overwrought approach that other adaptations have brought to the final scene.

Nineteen Eighty-Four can currently be viewed on Prime. The print is a bit grainy but that only adds to the film’s power. It comes to us like a hazy vision of the future.

Other Entries In The 18 Days Of Paranoia:

- The Flight That Disappeared

- The Humanity Bureau

- The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover

- The Falcon and the Snowman

- New World Order

- Scandal Sheet

- Cuban Rebel Girls

- The French Connection II

- Blunt: The Fourth Man

- The Quiller Memorandum

- Betrayed

- Best Seller

- They Call Me Mister Tibbs

- The Organization

- Marie: A True Story

- Lost Girls

- Walk East On Beacon!