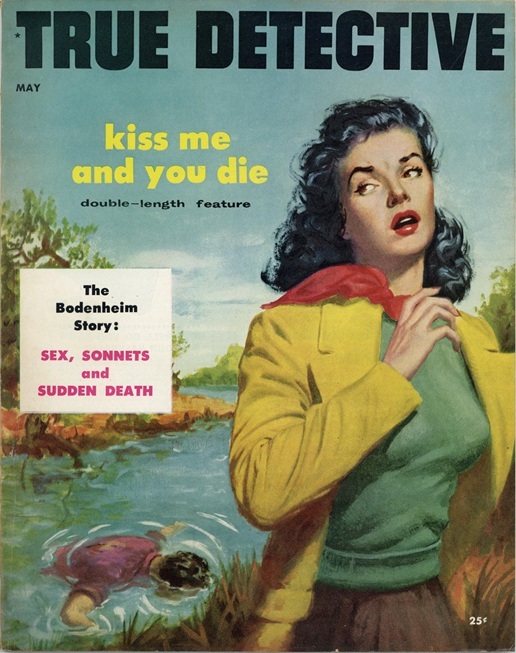

This watery cover is from 1954,

Share this:

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

The Prophetic Mussar of the Tohor midda of t’shuva

The Torah Parashat Vayishlach בראשית לד-לו addresses time-oriented commandments wherein “time” refers to wisdom rather than literal time tick-tock past history narratives. This Torah portion navigates complex stories which includes genealogies that embody deeper moral and ethical rebukes which later generations need to explore as understood through the wisdom of Mussar; a Jewish ethical, educational rebuke: active pursuit of fair restitution/compensation to the victim—rather than mere emotional guilt or substitutionary atonement. The relationship dynamics between Jacob’s family and the people of Shechem illustrate the significance of respecting sexual boundaries and ensuring that interactions conducted with both respect & honor. This contrasts sharply with certain Christian theological models of repentance, where forgiveness is framed through vicarious sacrifice, often without direct address of the victim’s pain or ongoing accountability.

T’shuva a key tohor middah. It fundamentally requires remembering the past through introspection, as exemplified through the month of Elul, Rosh HaShanna and Yom Kippur. This “wisdom” makes no attempt to justify past reactionary folly. But rather attempts to weigh the need to address the nature of damages inflicted upon others which requires some kind of mutually agreed upon fair compensation of damages. The Prince and people of Sh’Cem sought to profit from their crimes, they never considered the need to fairly compensate the Yaacov and his family for the rape of his daughter. Simeon and Levi massacre the males, rescue Dinah, and the other brothers plunder the city. Jacob rebukes them for endangering the family, but they retort: “Should he treat our sister as a harlot?” (p’suk 34:31)—highlights their raw demand for justice, even if their method exceeds Torah bounds. Jacob’s return to Bethel, Rachel’s death in childbirth, and Esau’s genealogy—highlighting continuity across generations

The genealogies imply that this wisdom of remembering past sexual folly, in order to due t’shuva – meaning pay some agreed upon terms or amounts to achieve some fair compensation of damages, greatly differs from the alien and utterly foreign substitute theology of repentance which totally ignores the pain suffered by the victims. Mussar principles of self-examination, character refinement, and moral accountability. T’shuva, a tohor middah, centers on honest remembrance of harm—especially sexual violation or disgrace (avoda zara dishonor in broader terms)—coupled with active, victim-centered restitution rather than emotional guilt or vicarious substitution. Esau’s extensive genealogy, underscore generational continuity: moral failings (or rectifications) simply don’t just disappear after the criminal generation dies out. War-crimes against Humanity never erased but must be confronted by descendants. Fear of Heaven means that peoples’ pursue t’shuva consequent to their ruined Good Name reputations, which might never heal across the span of generations.

Guilt theology, such as ‘this false messiah died for you’ not the same thing as remembering past personal, in this specific case sex disgrace or avoda zara dishonor. This significant distinction – a vital Mussar k’vanna throughout the T’NaCH, Talmud, and Midrashim. Which embodies the principles of accountability, respect, and reflection, absolutely symbolized through Torah judicial court-trials, which make fair restitution of damages inflicted – as exemplified by the 10 plagues and the splitting of the Sea of Reeds.

True t’shuva requires an honest acknowledgment of one’s sexual missteps, facilitating a path towards genuine correction and healing that others have suffered. The narratives compel us to reflect on past actions rather than ignore them, emphasizing that growth comes from inevitable missteps and the commitment to make amends. This t’shuva simply crucial for both individuals and communities seeking to forge healthy relationships. The detailed lineages rebuke the generations that moral failings (or corrections) pass down. Each generation must reflect on predecessors’ actions, rectify where possible, and avoid repeating past folly. This collective responsibility rejects “be here now” spiritual hippie individualism. Instead it fosters an ongoing ethical growth in families and communities.

The actions of Shechem and his father highlight a critical ethical breach: the attempt to profit from wrongdoing without appropriate restitution. In contrast, the expectation of justice in Jewish law mandates compensatory measures for harm done. This underscores the significance of fairness and moral responsibility in interactions. The judicial trials and structures presented serve as models for community accountability. They reinforce the idea that restitution: not simply limited to mere transactional affair, but an ethical obligation that reflects respect for the victim and for communal harmony. The 1939 British White Paper triggered the Shoah as did American pride which now viewed refugee populations as inferior scum on par with Christ-Killer slanders.

American attitudes in the 1930s–1940s reflected restrictive immigration quotas, intensified by the Great Depression, isolationism, and widespread antisemitism—including lingering “Christ-killer” slanders that portrayed Jews as collectively responsible for Jesus’ death, fueling prejudice. The 1938 Évian Conference (convened by FDR) exposed global reluctance: most nations (including the U.S.) refused to expand quotas for Jewish refugees, even post-Kristallnacht. Polls showed strong American opposition (e.g., ~72% against more Jewish immigrants in late 1938), sometimes viewing refugees as undesirable or inferior—echoing demeaning stereotypes. This collective failure to act, prioritizing national interests over humanitarian rescue, parallels the Shechemites’ self-serving avoidance of true restitution.

The genealogical refrains in these chapters further embody the continuity of responsibility across generations. They remind us that recognizing and rectifying past wrongs not limited to an individual personal journey. But rather a collective one, where each generation – called to learn from and address the failings of those before them. The ‘born again Xtian’ represents a total negation that limits faith to “be here now”. The narratives of this Torah prophetic mussar therefore serves as a powerful Aggadic/Midrashic story in the T’NaCH tradition which punctuates the importance of accountability, respect, and fair restitution.

Through introspection and a commitment to t’shuva, individuals and communities strive to navigate their moral landscapes, with the common goal of achieving integrity in communal relationships and actions. This wisdom encourages a richly nuanced understanding of justice which emphasizes and prioritizes the transformative power of genuine reflection and ethical responsibilities, promoting healing and mutual respect among and between Jewish marriages and families. This prophetic call in Vayishlach urges ethical integrity, respect for boundaries (sexual and otherwise), and ongoing responsibility, vital for Jewish continuity and mutual honor in relationships.

LikeLike